In the past four years, sustainment of stand-in forces has grown in importance, especially for U.S. Indo-Pacific Command. The 38th Commandant of the Marine Corps, General David H. Berger, laid a new course for future force design and modernization with the 2019 release of his Commandant’s Planning Guidance. In “Together We Must Design the Future Force,” (Proceedings, November 2019), the Commandant highlighted the need for the Navy and Marine Corps to maintain a forward presence within an “adversary’s near seas,” thereby turning those areas “into mutually denied spaces.” There, and in follow-on documents, he noted that the joint force would no longer enjoy uncontested air and sea access to these regions, emphasizing that, for maritime forces to persist within contested areas, they must change how they have traditionally operated.

To do so, the Navy and Marine Corps are seeking new platforms to mitigate vulnerabilities that result from an adversary’s long-range, antiaccess/area-denial (A2/AD) capabilities. One such platform will be the new landing ship medium (LSM). To complement it, the blue-green team could repurpose an overlooked, underutilized, and underfunded but capable class of watercraft. The Improved Navy Lighterage System (INLS) is a modular system that has been the backbone of the Maritime Preposition Force (MPF) for more than 15 years. INLS provides ship-to-shore movement (STSM) capabilities for the sailors and Marines tasked with lightering massive amounts of cargo to sustain forces ashore.

INLS modules—such as the causeway ferry, floating causeway, warping tug, and roll-on/roll-off discharge facility (RRDF)—possess many of the necessary capabilities identified in Force Design 2030, the Tentative Manual for Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (EABO), and A Tentative Manual for Stand-in Forces. A single, 270-foot by 24-foot by 8-foot causeway ferry module can carry 300 tons of equipment at 10 knots approximately 350 nm unrefueled, while maintaining a three- to four-foot draft. The RRDF modules are versatile, capable of interfacing with the MPF vessels (including LCM-8 and LCU-1600 landing craft) and all Navy and Army watercraft in the existing inventory. INLS can perform instream stern ramp offload of Military Sealift Command medium-speed roll-on/roll-off ships as well as LCU-2000s and expeditionary fast transports. These capabilities enable INLS to offload equipment from Navy or commercial ships, transfer assets from one vessel to another, and conduct traditional STSM or shore-to-shore operations.

A multimission platform, INLS can be used as a temporary bridging solution. It is mobile, and its platforms have low radar and infrared signatures and can operate easily in the littorals or open ocean (through sea state 3) with minimal risk of detection by surface platforms. (They would be vulnerable, as all surface vessels are, to satellite and overhead visual and electronic detection.) But constant movement of personnel and materiel could support efforts to confound an adversary’s ability to determine the location and destination of the most critical Navy and Marine Corps assets.

With such versatility, INLS can support additional missions. Lightering activities often use less than 20 percent of a module’s 15,500-cubic-foot internal capacity. Original INLS concept development envisioned additional modules that would allow for reverse-osmosis water purification, berthing, galley, warehouse, and repair shop operations—and even fuel and munitions storage.

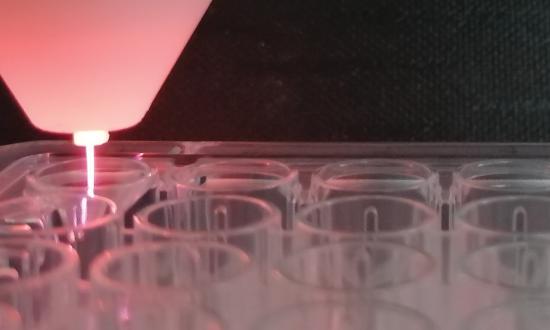

For example, in July 2020, Naval Facilities Engineering and Expeditionary Warfare Center and the Army’s Engineer Research and Development Center tested a new small-scale fuel distribution system. Employing an RRDF platform, Naval Beach Group Two at Little Creek, Virginia, constructed an experimental amphibious forward arming-and-refueling platform (FARP), on which Army helicopters landed and simulated fueling and maintenance operations, repurposing the 72-foot by 255-foot RRDF to act as an 18,000–square foot floating landing, refueling, and servicing platform.

Capabilities such as these would enable the platform to perform ship-to-shore movements as needed while simultaneously supporting stand-in forces and managing their materiel needs from offshore. In addition, incorporating many of these proposed modules into the INLS fleet would enable INLS to lighter farther or loiter longer, better supporting EABO, distributed maritime, forward arming and refueling, special, and riverine operations.

INLS capabilities save time, cost comparatively little, and can help remediate the challenges faced by the Navy and Marine Corps today and in the future.

First, however, commanders need to know the program exists to test and employ its capabilities. Fielding a new platform—through resourcing, planning and testing, training, and deployment—is not quick. Likewise, building fixed infrastructure is time-intensive and expensive, and the end product is vulnerable throughout its lifecycle.

Expanding INLS capabilities is the fastest route to supporting the stand-in force. An INLS floating causeway or RRDF can be on station and assembled in a week or two, depending on the point of origin. While INLS does not offer the permanent presence that partners and allies sometimes prefer, U.S. forces can use these platforms to mobilize personnel and materiel during competition, contingency, HA/DR operations—and conflict. They can reassure allies and give flexibility when operating with partners who prefer less restrictive arrangements.

The platforms exist. They should be put to innovative use.