Since World War II, the U.S. experience with warfighter trauma has come primarily from land wars. Data from the Department of Defense (DoD) Joint Trauma System in 2009 showed a significantly lower fatality rate for soldiers wounded in Iraq rather than Afghanistan. The so-called golden hour “presumes that some deaths are preventable if appropriate care is provided by appropriately trained individuals with the right lifesaving or life-sustaining equipment . . . at the right time.”1

That presumption gained support from the conclusion of the DoD study: The average time to hospital was one hour in Iraq and two hours in Afghanistan. Further enhancing outcomes, severely wounded soldiers were transported by critical air transport teams for more advanced care in Germany and the United States within days of injury. In the South China Sea, to consider one possibility, China’s antiaccess/area-denial networks will challenge combat casualty care, especially for casualties at sea. Such threats to medical evacuation could create a need to treat injured troops away from U.S. facilities for days, weeks, or even months after injury.

The Navy and Marine Corps need to do more to deal with traumatic injuries from war at sea and in contested littorals. This will require equipping naval medical personnel with the latest technologies for point-of-injury care, including cold atmospheric pressure plasmas (CAPPs). CAPPs use electricity to turn nontoxic gases into germ-killing agents.

Seawater has multiple roles in exacerbating trauma, including cold temperatures, hypertonicity (salt-driven water loss), and infections by pathogenic bacteria. China is developing a tiered structure for war at sea that mirrors the U.S. evacuation system. China’s navy also is investigating prevention of and therapy for bacterial infections related to seawater, including assessing the varieties, counts, and antibiotic susceptibility of bacteria in Southeast Asian littorals. The United States is approaching war-at-sea combat casualty care primarily as a logistical challenge that can be solved within a joint functional commander construct.2 But dispersed and disaggregated forces will make the golden hour rule difficult to achieve in the face of mass casualties on critically damaged ships.

Our December 2021 article in Frontiers of Physics describes how CAPPs provide “a promising biophysical tool to address these issues by applying physically created modalities that cannot be circumvented by bioresistance,” which prevents microorganisms from becoming active infections.3 Medications can lead to resistance in pathogens, but CAPPs use a physical means to block them that they cannot resist. CAPPs have demonstrated the ability to treat burns, control bleeding, and do other things that enhance wound healing.

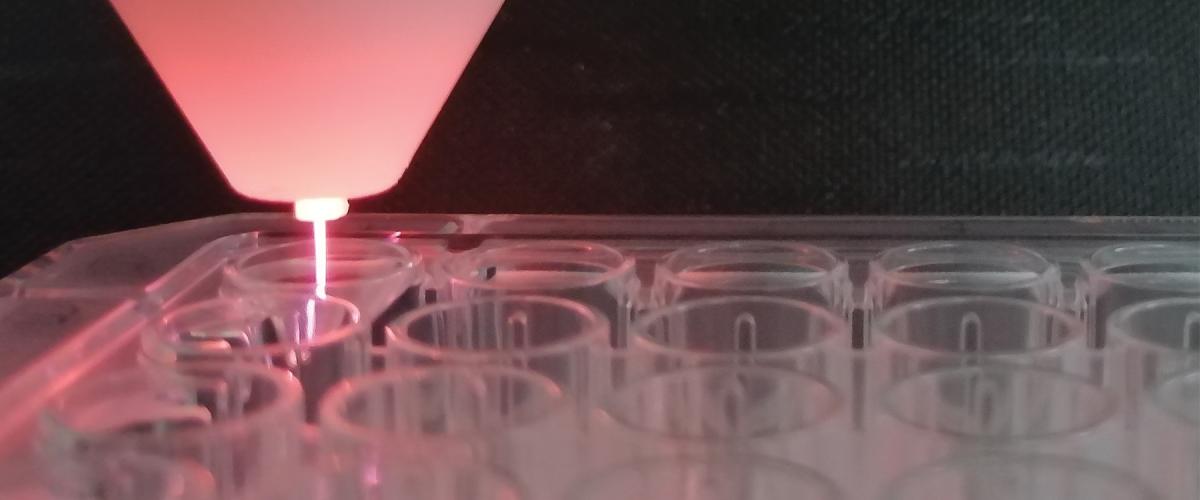

A CAPP is a controlled electrical discharge in a selected mixture of nontoxic gases. The plasma results from the application of high voltage to a gas at atmospheric pressure, generating an electrical breakdown. Think of small arcs from static electricity or when putting a plug into an electrical outlet. The ionized gas formed during breakdown is plasma, often called “electric plasma” to avoid confusion with the liquid plasma that is a component of blood. CAPPs formed in air contain a mixture of charged particles, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), which are created through chemical reactions between air and water vapor.

While some CAPPs use specialized gases, others use atmospheric air, which minimizes supply chain issues, and some systems can operate on battery power for portable device field use.

CAPP air-filtration technologies need further research and custom engineering for each application. Even so, CAPPs are on the verge of becoming a portable technology that can extend the golden hour by providing point-of-injury treatment wherever evacuation to higher-level care is not practical.

Antibiotics such as penicillin biochemically create ROS that kill bacteria; but bacteria are learning to disrupt these processes, meaning “the post-antibiotic era” has arrived.4 With CAPPs, the electrical rather than biochemical processes for creating ROS/RNS mean the plasma method is effective in killing even antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria, including E. coli, diphtheria, streptococcus, and anthrax.

Viruses also are of concern. CAPPs have inactivated viruses on surfaces and killed 99.9 percent of airborne viruses in trials.5 The equipment and protocols for decontaminating surfaces for bacteria, spores, and viruses will likely be similar to those for wound treatment. The threat of synthetic bioweapons was a topic at the 2018 Breaking the Mold 2.0 leadership event at the U.S. Naval War College.6 The exponential growth of commercial synthetic biology tools was deemed a credible emerging threat, and CAPP technologies were mentioned as a potential mitigation technology.

But CAPPs can be beneficial to mammalian cells beyond killing pathogens. CAPPs directly stimulate healing and can stop bleeding atherm-ally by inducing clotting. They also can be used in biological decontamination of structures, medical equipment, implants, and wounds by killing microorganisms and/or inactivating spores, reducing the hazards associated with chemical decontaminants and disinfectants.

Bring CAPPs to Warfighters

Plasma medicine got its start in the mid-1990s through visionary investments by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR).7 AFOSR funded CAPP studies until the program fell victim to debates over whether scientist-led human performance research versus physician-led medical research should be supported. Until recently, no service or DoD basic research office included CAPP-related research on its approved list of topic. From 2005 to 2008, DARPA and the National Science Foundation (NSF) funded an applied research project in plasma medicine at Drexel University, but that work was discontinued.8 A research project in the Naval Research Laboratory Plasma Physics Division has studied the physics of plasma-surface interactions in CAPPs, but the biology/medicine component has been missing.

Perhaps this reflects the “fear of medicine” in the physical sciences and the “fear of physics” in the medical research community. Dr. Timothy Bentley supported one of us in writing the Frontiers of Physics article on CAPPs for trauma and acute care as part of his Naval Force Health Protection Program in the Office of Naval Research. He has also supported a small CAPP-related project at Rice University. This is an encouraging start, but more basic and applied research must be done to clarify the underlying interaction mechanisms and to provide informed guidance to lead the optimization of CAPP technologies for battlefield trauma care.

Elsewhere, electric plasmas have grown from proof-of-principle in vitro studies to practical devices for wound healing, microorganism inactivation, cancer therapy, and agriculture, which have been commercialized and used for clinical studies in Europe, Russia, and Asia. The German atmospheric-pressure plasma jet kINPen® MED has received market approval and is used in dermatology and wound treatment. In recent years, China has published extensively on applying CAPPs to trauma care and other diseases, including cancer.

The United States needs to regain leadership in cold atmospheric plasma science and technology. The Department of Defense should bring this critical-care technology to warfighters. The Navy could be a catalyst by building on the nascent efforts in its own research organizations. Ideally, this would become a joint effort: The Navy has the only plasma physics division; AFOSR has a plasma physics program officer; and the Army is the executive agency for biology. The many DoD medical organizations also need to become involved. All would benefit from this capability, and a transition from the military to the civilian medical system, with initial DoD data, could help speed Food and Drug Administration acceptance of this new technology. This could also help realize the National Academies of Science 2016 recommendation to develop a joint national trauma care system that integrates military and civilian systems.

The People’s Liberation Army may be planning to use CAPPs for medical treatment. China already has home field advantage in the South China Sea. Does the United States also want China to have an asymmetric advantage in trauma care from an idea that originated with U.S. Air Force–sponsored research?

1. Tanisha M. Fazal, Todd Rasmussen, Paul Nelson, and P. K. Carlton, “How Long Can the U.S. Military’s Golden Hour Last?” War on the Rocks, 8 October 2018.

2. Dion Moten, Bryan Teff, Michael Pyle, Gerald Delk, and Randel Clark, “Joint Integrative Solutions for Combat Casualty Care in a Pacific War at Sea,” JFQ: Joint Force Quarterly 94, no. 3 (July 2019).

3. Allen Garner and Thomas Mehlhorn, “A Review of Cold Atmospheric Pressure Plasmas for Trauma and Acute Care” (in English), Frontiers in Physics 9, no. 774 (December 2021).

4. Heleen Van Acker and Tom Coenye, “The Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in Antibiotic-Mediated Killing of Bacteria,” Trends in Microbiology 25, no. 6 (June 2017): 456–66.

5. “Cold Plasma Can Kill 99.9% of Airborne Viruses, U-M Study Shows,” University of Michigan News, online, 19 April 2019.

6. “Breaking the Mold: Consolidated Report on the Workshop,” Naval War College, March 2018.

7. Kurt H. Becker et al., “Robert Barker Memorial Session: Leadership in Plasma Science and Applications,” IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science 43, no. 4 (April 2015): 914–36.

8. Gregory Fridman et al., “Applied Plasma Medicine,” Plasma Processes and Polymers 5, no. 6 (August 2008): 503–33.