Formal fleet damage control training happens in the basic phase and focuses on peacetime operations rather than combat. Basic-phase training, which ships often conduct while independently operating, aims to certify crews to the minimum standard to safely operate a ship and her weapons. During these rather unrealistic training scenarios, equipment casualties are isolated and evenly distributed throughout the ship, damage control equipment always works, and personnel casualties are light or nonexistent. Yet, historically, combat damage is catastrophic, chaotic, and lethal. Spaces are simultaneously flooding and burning. Damage control equipment is destroyed. Many sailors are dead or seriously injured.

For damage control training to be of maximum value, the experience from real combat damage control must be the basis for more intense, complex exercise scenarios—sailors wading through flooding to contain fires, destroyed damage control equipment, the bodies of shipmates floating nearby, etc. To prepare Navy ships for combat, advanced-phase training must include combat damage control.

Combat Damage Control Training

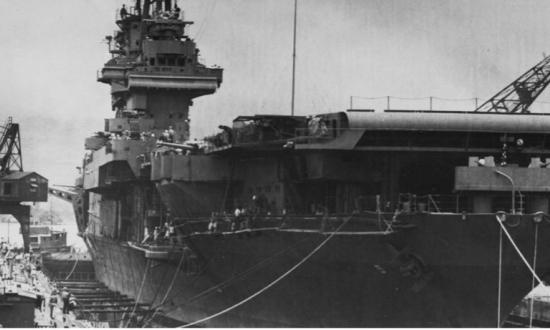

Ships from World War II through the 1980s Tanker War found themselves simultaneously fighting fire and flooding in adjacent spaces, if not in the same space. Severed electrical cables, burning fuel spills, and fires in the overheads as water rises lead to spaces in which sailors must contain flooding while beating back fires.

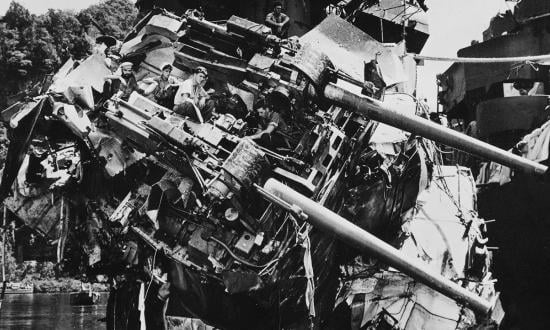

Realistic advanced-phase training must include loss of damage control equipment to prepare sailors for combat. Loss of power and shattered pipes denied access to critical damage control equipment to the crews of the USS Fanshaw Bay (CVE-70), Johnston (DD-557), Aaron Ward (DM-34), both Samuel B. Roberts (DE-413 and FFG-58), and Stark (FFG-31), requiring sailors to improvise solutions and fight for their ships with little but blood and sweat.1 Off Okinawa in 1945, the Aaron Ward’s crew formed bucket brigades with empty shell casings to contain fires until the firemain could be restored.2

Realistic advanced-phase training must also include heavy personnel casualties to prepare sailors for combat. The USS Hoel (DD-533) lost 16 men to one shell hit and ultimately lost 253 of 336 men off Samar, while the Aaron Ward lost 42 of 351 men to kamikazes off Okinawa.3 In the missile age, HMS Coventry suffered 19 killed and 30 wounded of 287 men, while the Stark suffered 37 killed and 21 wounded of 200 men at the start of the Tanker War.4 These ships suffered an initial casualty rate of 16–30 percent, and similar results can reasonably be expected for ships damaged in future combat. Additional casualties from heat and exhaustion will further degrade crew capabilities as damage control efforts continue. In combat, carefully constructed watchbills and meticulously managed qualifications are shredded in an instant, leaving junior personnel to pick up the pieces and fight through as best they can. Heavy personnel casualties are the most dangerous—and least trained to—aspect of combat damage control.

The most common objection to high-fidelity damage control training is that every scenario must give equal training to all personnel. The Navy must not accept this excuse. If some personnel do not receive training in a given scenario because they are “killed” at the outset, they will participate in the next drill when others are killed.

If two repair lockers are not being trained because the missile impact is only being fought by the nearest repair locker, damage was not realistically severe, and the scenario must be revised. History has shown that combat damage control requires the effort of all surviving personnel to keep ships afloat. If Navy training does not reflect this reality, then Navy leaders are failing their sailors.

Crew confidence is built by giving them challenging, realistic training. Carl von Clausewitz spoke of “the supremacy of the moral factors.”5 The chief machinist’s mate in the forward engine room of the Aaron Ward-—with fires raging and main spaces flooding—said, “The ship won’t sink—the old man wouldn’t stand for it.”6 When told that they must brace a sagging bulkhead that would drown them and sink the ship if it failed, sailors on board the Samuel B. Roberts (FFG-58) replied, “This is nothing, you should see the next space.”7 These quotes have the same message—a motivated crew with confidence in themselves and their training will win.

To properly train ships, training and operational readiness requirements in the advanced training phase must be adjusted to require simultaneous fire and flooding, loss of damage control equipment, and personnel casualties in shipboard drills. In addition, scenarios based on historical battle damage and tailored by ship class must be constructed. For example, a scenario could model that warhead A targeting ship B and detonating at point C will crack pipe D, degrading system E with watchstander indication F. If pipe D is not isolated by time G, flooding progresses to space H, with follow-on casualty I to system J. Training for combat means training for the aftermath of the initial engagement and fighting through battle damage, which is why the advanced phase exists.

Navy leaders owe it to sailors to give them training that will keep them alive and their ships afloat in war. When a 400-pound warhead impacts a ship, damage control systems may disappear in a cloud of superheated shrapnel. Combat damage control training must take this into account. Training must also include catastrophic personnel casualties to prepare crews for the gaps they will have to fill and the friends they will have to treat while the ship burns around them. Training must recognize the possibility of failure and have branch plans for spreading casualties as sailors stumble through a critically wounded ship.

While damage control training today does not do this, adding combat damage control training to the advanced training phase would better prepare ships for combat. The basic phase trains sailors to handle hoses and patch pipes. The advanced phase must train sailors to save their ships in war.

1. James D. Hornfischer, The Last Stand of the Tin Can Sailors (New York: Bantam Books, 2005), 217, 278, 298; Arnold S. Lott, Brave Ship, Brave Men (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1994), 175; and Lee Allen Zatarian, Tanker War: America’s First War with Iran, 1987–1988 (Philadelphia, PA: Casemate, 2009), 190.

2. Lott, Brave Ship, Brave Men, 175.

3. Lott, 192.

4. David Hart Dyke, Four Weeks in May: A Captain’s Story of War at Sea (London: Atlantic Books, 2008), 154; and Zatarian, Tanker War, 190.

5. Carl von Clausewitz, On War (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976), 184.

6. Lott, Brave Ship, Brave Men, 193.

7. Zatarian, Tanker War, 13.