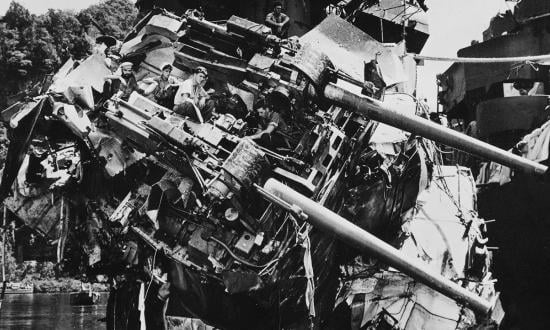

In any future conflict in the Pacific against China, the U.S. fleet will experience battle damage on a scale not seen since World War II—a situation today’s Navy is woefully unprepared to handle. Two decades of counterinsurgency and poorly planned divestments have stripped the service of the capabilities it needs to rapidly return ships to the fight. Given the tyranny of distance and a domestic shipbuilding industrial base far smaller than China’s, the Navy needs to develop and reestablish a system for forward battle damage repair.

The Navy’s current ship-repair process is slow, reliant on fixed shore-based facilities, and would be unsustainable during a large conflict of any duration. Even the 74-day Falklands War, a moderate-intensity conflict against a militarily inferior opponent, left the Royal Navy with 13 battle-damaged ships, not counting the six that were sunk.1 The U.S. Navy today likely would struggle to conduct battle damage repair even on this modest scale.

The 2017 collision involving the USS Fitzgerald (DDG-62) highlighted flaws in the Navy’s current model of battle damage repair.2 Following immediate damage-control efforts, the ship was stabilized, placed on a foreign-flagged heavy-lift ship, and moved to a stateside shipyard for repairs—returning to active duty three years later.3 A peer conflict would not allow for repairs of such duration, and the Navy’s overreliance on civilian contractors and shipyards for much of its diving and salvage work leaves it no organic repair capacity to handle even accidents in peacetime.4

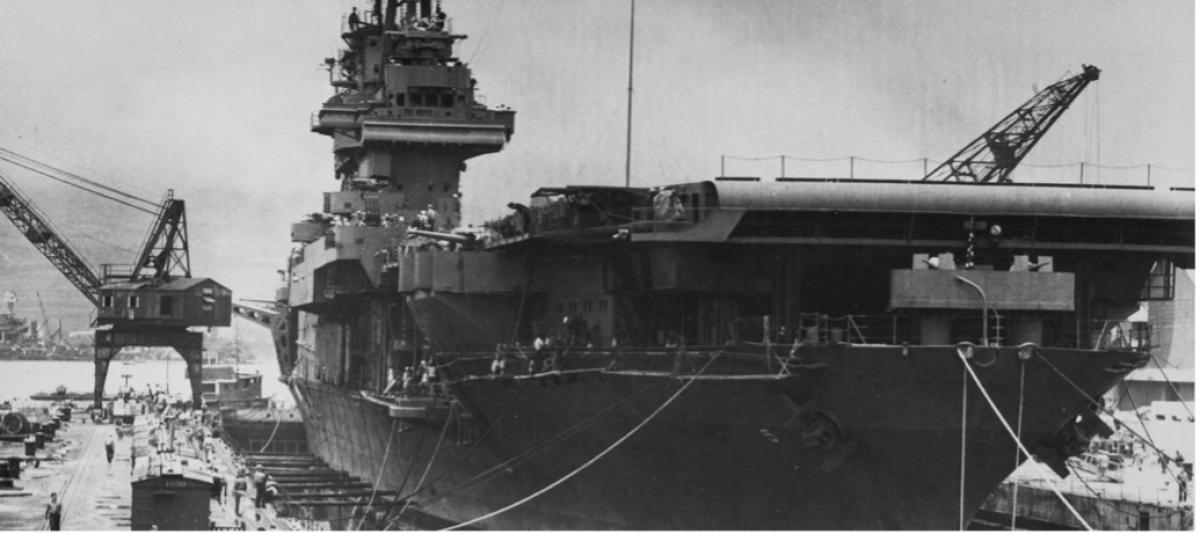

In a conflict against a peer adversary, any additional time without an operational combatant could have devastating consequences. A key factor in the U.S. victory at Midway was the return of the USS Yorktown (CV-5)—damaged at the Battle of the Coral Sea—to a mission-capable status after just three days of hasty repairs.5

With a much smaller surface combatant fleet than China’s, the Navy will need as much capability as it can squeeze out of its surface fleet. Returning battle-damaged ships to operational capability will provide combatant commanders flexibility and more resources available for tasking. Lessons from expeditionary battle damage repair during World War II provide some inspiration for the recapitalization of this capability.

World War II Service Squadrons

During World War II, service squadrons were stood up in the Pacific to provide expeditionary logistics support and forward battle damage repair. These squadrons consisted of hundreds of vessels of various sizes and were based at atolls far closer to the maritime battlespace than the nearest land-based support facilities at Pearl Harbor.6 With tenders, repair ships, and floating drydocks, they provided the fleet urgent damage assessment and repair capabilities over the course of the war. As a result, ships were returned to the fight or were sufficiently patched up to safely make the slow journey to larger support facilities on the West Coast or at Pearl Harbor.

Although the service squadrons were mobile and forward deployed, they remained at one location for months at a time and were centered around huge expeditionary logistics hubs. This would be undesirable in a modern maritime conflict. Persistent intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance and long-range antiship/strike weapons would make colossal logistics hubs such as the one created on Ulithi untenable. A service squadron concept today would have to be more expeditionary to be survivable and continue to provide the fleet with an organic battle repair capability.

A Modern Take

A notional 21st-century service squadron could center around a large legacy tender supporting one or two heavy-lift ships serving as mobile floating drydocks. As pressure on the shipbuilding budget already is high, purchasing and modifying commercially available ships might be the best option. Four to eight modified commercial ships could serve as small tenders, depot, repair, and crane ships. Offshore support vessels, commonly produced in small shipyards in the United States, would be ideal for conversion to small tenders and crane ships.7 Their low cost, ready availability, and simple design make them especially amenable to modification. Multiple small tenders and repair ships, supported by a handful of larger vessels, would increase the survivability of the squadron and its capabilities.

Commercial ship conversions alone, however, would not provide sufficient repair capacity for a modern service squadron. Some repair functions can be undertaken only by large tenders, such as the Navy’s two submarine tenders, the youngest of which is 42 years old.8 The Navy should use the proposed Common Hull Auxiliary Multimission Platform (CHAMP) as a baseline to construct new submarine and destroyer tenders.9 These new tenders would serve as command ships for the squadrons, providing the core repair and command-and-control capabilities. Large tenders’ ability to deploy on their own allows them to individually support smaller conflicts and peacetime service.10

The service squadrons should be organized to be scalable for the different repair demands of peace and wartime. To that end, the large tender flagship would be manned by active-duty sailors and be a commissioned ship, providing regular support to the fleet in peacetime. The squadron’s smaller tenders and repair ships would be manned primarily by reservists and would not regularly deploy outside of exercises and wartime. They would provide a latent repair capacity to meet wartime surge requirements. To maintain their skills, reservists could support exercises that focus on battle damage repair, similar to the salvage training conducted on the ex-USS Bonhomme Richard as she made her way to be scrapped in 2021.11 Reservists also could be rotated through public shipyards, as they were in 2020 to support a workforce depleted by the COVID-19 pandemic.12 A mixed active and reserve force structure would allow the service squadron to be affordable and scalable to changing repair demands.

Acting in unison, modern service squadrons could maneuver around the Pacific from anchorage to anchorage supporting the fleet. They would be able to disperse across the outer edge of the weapons engagement zone and maritime battlespace to support a handful of battle-damaged ships at a time. For especially large concentrations of battle damage, multiple service squadrons could converge to support repair efforts.

A distributed architecture should not be seen as diluting the repair capability of the service squadrons. A modern service squadron would not be able to replace all the capabilities of a shore-based shipyard; modern warships are far too complex to include every repair capability in an expeditionary repair force. The primary mission of a service squadron would be to restore a ship’s mission capability or stabilize it sufficiently for transit to shoreside support facilities, where a thorough repair and rebuild process could take place.

For example, consider a frigate arriving at a service squadron’s anchorage with her flight deck warped by fire and with damage to her towed array sonar, main gun, and air-search radars. While repairing all the damage could be feasible, if the area combatant commander had a shortage of antisubmarine warfare capable ships, the squadron could rush only to replace the towed array and repair the flight deck, returning the frigate to combat with her antisubmarine capability restored and with the remaining damage stabilized. Providing this flexibility to combatant commanders would increase warfighting options for the Navy’s benefit.

Incurring battle damage is inevitable in maritime conflict. The ability to expeditiously repair ships and return them to the fight is critical to winning against any adversary. Establishing a modern service squadron, drawing on lessons from the past and adapted for survivability in the future, will allow the Navy to affordably reestablish the capability to support forward battle damage repair.

1. “British Ships Lost & Damaged: 1st May to 12th June 1982,” NavalHistory.net, www.naval-history.net/F62-Falklands-British_ships_lost.htm.

2. Government Accountability Office, Navy Ships: Timely Actions Needed to Improve Planning and Develop Capabilities for Battle Damage Repair (Washington, DC: Government Accountability Office, June 2021), www.gao.gov/assets/gao-21-246.pdf. Accessed 26 Nov. 2021.

3. “USS Fitzgerald Arrives in Pascagoula for Restoration,” news release, Naval Sea Systems Command, 19 January 2018, www.navsea.navy.mil/Media/News/Article/1419438/uss-fitzgerald-arrives-in-pascagoula-for-restoration/; Megan Eckstein, “USS Fitzgerald Arrives in San Diego,” USNI News, 2 July 2020, https://news.usni.org/2020/07/02/uss-fitzgerald-arrives-in-san-diego-uss-mccampbell-leaves-japan-for-lengthy-upgrade-period.

4. Government Accountability Office, Timely Actions Needed.

5. David Lee Bergeron, “Fighting for Survival,” Naval History 33, no. 6 (December 2019), www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2019/december/fighting-survival.

6. U.S. Bureau of Yards and Docks, Building the Navy’s Bases in World War II: History of the Bureau of Yards and Docks and the Civil Engineer Corps, 1940-1946, vol. 2 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1947), 331–35. The most famous was at Ulithi Atoll in the Marshall Islands.

7. U.S. Maritime Administration, The Economic Importance of the U.S. Private Shipbuilding and Repairing Industry (30 March 2021), www.maritime.dot.gov/sites/marad.dot.gov/files/2021-06/Economic%20Contributions%20of%20U.S.%20Shipbuilding%20and%20Repairing%20Industry.pdf.

8. Mike Smolinski, NavSource Online: Service Ship Photo Archive, USS Frank Cable (AS-40), www.navsource.org/archives/09/36/3640.htm.

9. John Pike, “Common Hull Auxiliary Multi-Mission Platform [CHAMP),” Global Security.org, www.globalsecurity.org/military/systems/ship/champ.htm.

10. Jonathan Trejo, “USS Frank Cable Begins Regional Indo-Pacific Patrol,” Navy.mil, 27 October 2021, www.navy.mil/Press-Office/News-Stories/Article/2825469/uss-frank-cable-begins-regional-indo-pacific-patrol/.

11. Richard R. Burgess, “Navy Puts Renewed Focus on Ship Battle Damage Repair,” Seapower, 18 October 2021, https://seapowermagazine.org/navy-puts-renewed-focus-on-ship-battle-damage-repair/.

12. Ben Werner, “Navy Calling Up 1,600 Reservists to Fill in for Shipyard Workers Out for Covid-19,” USNI News, 12 June 2020, https://news.usni.org/2020/06/11/navy-calling-up-1600-reservists-to-fill-in-for-shipyard-workers-out-for-covid-19.