The drama of the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis and the White House Executive Committee’s decisions—including to “quarantine” Cuba with U.S. warships—has been told and retold. Less well known is how that quarantine fleet was assembled at lightning speed by the Navy and steamed into action.

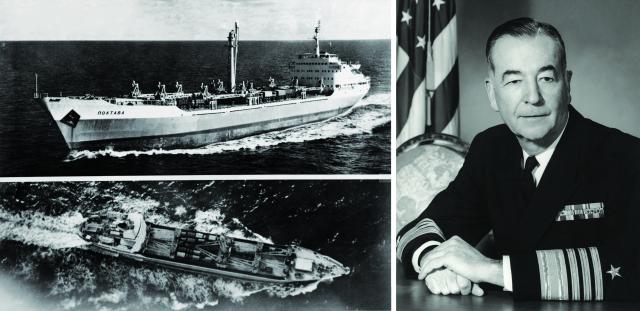

In these edited excerpts from his 1972 Naval Institute oral history, retired Navy Admiral Alfred G. Ward, who commanded the quarantine fleet, recounts the action:

I was sitting in my office one Wednesday having had command of the amphibious force for about 13 months, enjoying my duty, when I had a call from a captain on the staff of Admiral Robert Dennison, Commander-in-Chief, Atlantic Fleet, who told me I was to be relieved the next day.

I said, “What have I done wrong?” He said, “I don’t know that.”

So I called Dennison’s deputy, Admiral Wallace Beakley, who confirmed the first message and called a bit later to say the change-of-command ceremony would be Friday, not Thursday, and my friend Horacio Rivero would be my relief. During the ceremony, notes were being passed to me saying, “Cut it short; you have work to do.” The ceremony lasted about two minutes.

The next morning I reported on board the Second Fleet flagship as Commander, Second Fleet.

Some of my ships were being ordered to sea that day. I called Admiral Beakley and asked what he was doing to my fleet, told him I wanted to see Admiral Dennison. He said Dennison wanted to see me. I should meet him at his airplane in 20 minutes.

During the 40-minute flight to Washington, Dennison briefed me that we would blockade Cuba, that I would be blockade commander and would be in charge of all operations around the island. He showed me some plans his staff had made on a blockade. Together we modified them somewhat, and immediately on arrival in Washington, we went to see the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

This was all moving very fast. Only a few people knew in advance that the decision to blockade, not invade or launch an airstrike, was actually made by President Kennedy in the White House. I was given a copy of the speech the President would make to the nation on Monday night using the word blockade. When he spoke, I was well out at sea, heard him on the radio, and the word blockade had been changed to quarantine.

When I had returned to Norfolk from Washington, I ordered additional tankers underway: “Go to sea and head toward the coast of Florida, additional instructions later.” Our destroyers also started heading out on the weekend. Their captains were told not to have a general recall of personnel over the radio. They were permitted to use the telephone. If they needed additional people, they were authorized to go to ships undergoing overhaul and borrow some of their people; many ships headed out with very reduced numbers of crew members. This was for a very dangerous mission in which they might have to shoot.

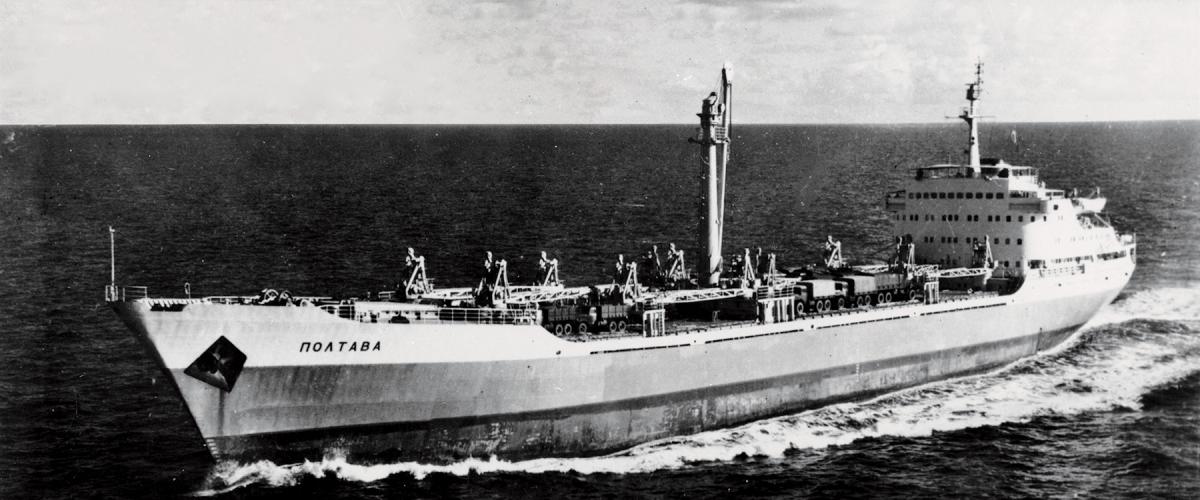

By Monday night, we were on station around Cuba and off the east coast of the Bahamas to stop ships going through those straits. None of us knew what would happen. We did not expect any large numbers of Soviet warships, but we could not know their reactions. For the first few days our ships were darkened and our guns manned, but after the decision by the Soviets to turn their ships carrying war supplies around and head back, we lighted ships and took people off their gun batteries, maintaining alert for antisubmarine warfare. We would stop some of their merchant ships and trail some of their submarines.

This was a powerful force we had in Task Force 135, including two carriers, the USS Enterprise [CVN-65] and the USS Independence [CV-62], both with their accompanying destroyers and a resupply ship. The amphibious forces were loaded with some 25,000 Marines. In the quarantine we acted calmly and forcefully but left room for a solution short of war.