The Cuban Missile Crisis was the closest the United States and the Soviet Union ever came to a nuclear exchange during the Cold War. Soviet submarines were the focus of the “gravest concern” for President John F. Kennedy during those 13 perilous days in October 1962.

The crisis evolved as the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev sought to overcome the overwhelming U.S. superiority in strategic nuclear forces by inserting nuclear missiles into Cuba. As part of that operation—code name Anadyr—the Soviet Navy was to send two Sverdlov-class cruisers, four destroyers, several submarines, a dozen Komar-type missile boats, support ships, and a regiment of 33 bomber aircraft to Cuba. The Komars each carried two antiship missiles; at the time, U.S. warships had no defense against those weapons.

However, Khrushchev soon canceled the deployment of naval ships to Cuba—except for the diesel-electric submarines. He had long argued against surface warships; following dictator Joseph Stalin’s death in March 1953, there were massive cancellations of surface warships. Khrushchev’s son, Sergei, recalled a later commentary on the subject by his father: “Mounting his favorite hobbyhorse, Father began a long and detailed recital of the advantages that a submarine fleet had over a surface fleet for the Soviet Union, a land power. . . . Finally, coming to the end, he snapped: ‘We’ll limit ourselves to four destroyers, one for each of the four fleets.’”1

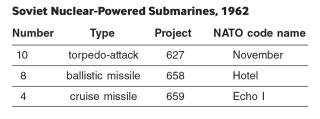

Significantly, no nuclear-powered submarines were dispatched to the Caribbean. The first Soviet nuclear submarine—a Project 627 (NATO November class)—went to sea in July 1958, almost four years after the USS Nautilus (SSN-571) got underway. By 1962, the Soviet Union had 22 nuclear submarines in service or on trials.

(At that time the U.S. Navy had 25 nuclear-powered submarines in commission, of which nine were Polaris ballistic-missile submarines.)

However, Soviet industry and naval maintenance activities could not adequately support the nuclear submarines, and a number of near disasters befell early Soviet “nukes.” Accordingly, only diesel-electric submarines were dispatched to the Caribbean.

The Cuban Missile Crisis demonstrated that Soviet diesel-electric submarines could operate at great distances and could have an influence on world events. As the U.S. Navy initiated a “quarantine” to stop Soviet merchant ships from bringing troops and weapons to Cuba, there was considerable concern among Navy leaders that Soviet submarines could interfere with the blockade.

On 24 October 1962, two days after President Kennedy announced the quarantine, the president of Westinghouse International, William E. Knox, met with Khrushchev in Moscow at the Soviet leader’s request. Reportedly, Khrushchev stated that stopping and searching Soviet merchant ships on the high seas “would be piracy” and that “the United States could stop and search one or maybe two, but if we did, he would instruct his submarines to sink the American naval vessels.”2

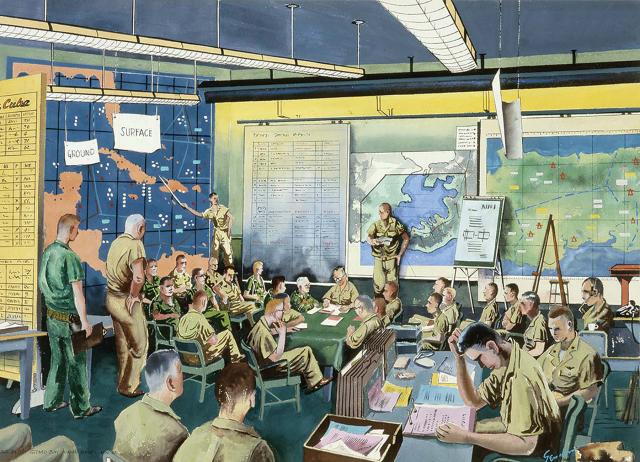

Significant U.S. antisubmarine warfare (ASW) forces were assigned to support the blockade operations and, if necessary, protect the amphibious forces as well as aircraft carriers in the event of an assault against Cuba. Those ASW forces included—at the height of the crisis—three ASW aircraft carriers with specialized sub-hunting aircraft on board, destroyers, and land-based maritime patrol aircraft. The last flew from bases in the the United States and at Argentia in Newfoundland, Canada (see “Cuban Crisis, Northern Vantage,” pp. 28–33).

In addition to forces that could “hunt and kill” Soviet submarines, the ASW effort included the highly secret Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS), the seafloor hydrophone arrays that sought out submarine sounds in the ocean. Their cross bearings on submarine noises would be used to cue ASW ships and submarines.

Thus, the U.S. Navy and those NATO navies with which it shared ASW/SOSUS intelligence were well aware that several Soviet diesel-electric submarines were in the western Atlantic by mid-October 1962. While SOSUS could easily detect the relatively noisy nuclear submarines, which had steam plants and hence pumps, water flowing through pipes, and other noise sources, diesel submarines—when submerged and drawing their power from electric batteries—were difficult to detect. Rather, it was when the conventional submarine came to the surface or extended a snorkel breathing tube to operate its diesel engines (to recharge batteries) that it could be easily detected by SOSUS and other means.

The Cuban crisis reached a critical point a few minutes after 1000 (Washington time) on 24 October, when Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara informed President Kennedy and his advisers that two Soviet freighters were within a few miles of the quarantine line, where they would be intercepted by U.S. destroyers. Each merchant ship was reported to be accompanied by a submarine, “and this is a very dangerous situation,” added McNamara.3

Robert F. Kennedy, the President’s brother and U.S. Attorney General, recalled, “Then came the disturbing Navy report that a Russian submarine had moved into position between the two ships.”4 The decision was made at the White House to have the Navy signal the submarine by sonar to surface and identify itself. If the submarine refused, small explosives would be dropped near the submarine (by helicopter or a destroyer) as a signal. Robert Kennedy recalled the concern over that single Foxtrot submarine: “I think these few minutes were the time of gravest concern for the President. . . . I heard the President say: ‘Isn’t there some way we can avoid having our first exchange with a Russian submarine—almost anything but that?’”5

At 1025 that morning, word was received at the White House that the Soviet freighters had stopped, and the crisis abated for the moment. The President’s trepidation was based on the assumption by Secretary McNamara and other officials—as well as the U.S. Navy’s leadership—that the Soviet submarine carried torpedoes with high-explosive warheads. A “spread” of several such torpedoes launched by a submarine could easily sink an American destroyer and possibly one of the large cruisers, or even an aircraft carrier enforcing the quarantine.

Unknown to President Kennedy—or anyone else in the U.S. government or Navy—the Soviet submarine that had been detected between the two merchant ships also carried one torpedo with a nuclear warhead. So did the other Soviet submarines in the area.

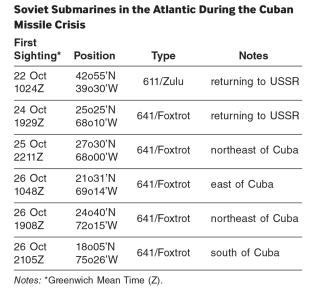

On 1 October 1962, five Soviet Project 641/Foxtrot submarines of the 69th Brigade had departed the Kola Peninsula en route to the Caribbean in support of Operation Anadyr. Another Foxtrot and an older Project 611/Zulu submarine were already in the western Atlantic. The Foxtrots were advanced, long-range diesel-electric submarines, the first of the type having entered service in late 1958. The submarines had six bow and four stern torpedo tubes and normally carried up to 12 reload torpedoes in addition to the ten in the tubes.

In addition to their conventional torpedoes, the submarines that departed their base on 1 October each carried one Type 53-58 nuclear torpedo.6 Developed under the designation T-5, it could be fired from standard 21-inch-diameter torpedo tubes. Its RDS-9 warhead had demonstrated an explosive force of ten kilotons in tests—more than one-half the destructive power of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombs.7

Rear Admiral Georgi Kostev, a veteran Soviet submarine commander and historian, later said, “Khrushchev believed that it was proper for the submarines, if the convoy would be stopped, to sink the ships of the other party.”8 When asked how he believed a nuclear war could have been sparked at sea, Admiral Kostev replied:

The war could have started this way—the American Navy hits the Soviet submarine [with a torpedo or depth charge] and somehow does not harm it. In that case, the commander would have for sure used his weapons against the attacker.

One of the Foxtrot commanding officers, Captain 2nd Rank Aleksey F. Dubivko of B-36, recalled that each submarine had been given instructions in a sealed envelope. It was to be opened only after a special radio signal was received, and with the submarine’s three senior officers present. Dubivko recounted:

I had my orders to use my weapons and particularly [the] nuclear torpedo only by instructions from my base. As far as I’m concerned, having received an order to use my nuclear torpedo, I would surely have aimed it at an aircraft carrier, and there were plenty of them there, in the area.9

Years later, another of the submarine commanders, Captain Second Rank Ryurik Ketov of B-4, said that their orders were:

Use the special weapon [nuclear torpedo] in the following cases: first, if they bomb and hit you; second, if they force you to surface and shoot at you on the surface; third, on orders from Moscow.10

The U.S. Navy initially had planned to use a heavy cruiser to intercept the first Soviet ship to reach the quarantine line, the 6,500-deadweight-ton Komiles, on 24 October. But the proximity of a submarine to the merchant ship led the Navy to decide to intercept the ship with a smaller destroyer because it had sonar and antisubmarine weapons. The intercept was to take place some 500 nautical miles from Cuba.

As U.S. officials waited for clarification as to whether the merchant ships had halted or were proceeding through the quarantine barrier, the submarine threat continued to dominate talk at the White House. Secretary McNamara explained:

The plan . . . is to send antisubmarine helicopters [from the carrier USS Essex (CVS-9)] out to harass the submarine. And they have weapons and devices that can damage the submarine. And the plan, therefore, is to put pressure on the submarine, move it out of the area by that pressure, by the pressure of potential destruction, and then make the [merchant ship] intercept. But this is only a plan, and there are many, many uncertainties.11

Secretary McNamara also explained some of those uncertainties as he informed his fellow officials about the difficulties of sonar detection and the relative range of submarine torpedoes. The intensive U.S. search located all six Soviet submarines in the Atlantic, albeit two of them on the surface and returning to bases on the Kola Peninsula—one Foxtrot and the older Zulu-class submarine.

One Foxtrot (pennant No. 945) from those that had departed on 1 October had suffered mechanical difficulties; she was sighted on the surface, en route back to the Kola Peninsula in company with the naval salvage tug Pamir.12 The Zulu also was sighted on the surface, refueling from the naval tanker Terek.

The submarine B-59, commanded by Captain Second Rank Valentin Savitsky, was forced to surface by U.S. destroyers in the Cuban area on 27 October, because her batteries were running low. His account of the conditions in his submarine and the encounter was spellbinding:

Only emergency lighting was functioning. The temperatures in the compartments was 45–50 C [113–122 F], up to 60 C [140 F] in the engine compartment. It was unbearably stuffy. The level of CO2 in the air reached a critical, practically deadly for people mark. One of the duty officers fainted and fell down. Then another one followed, then the third one. . . . They were falling like dominoes.13

The account, as told to a Russian journalist, continued:

The totally exhausted Savitsky, who in addition to everything, was not able to establish [a radio] connection with the General Staff, became furious. He summoned the officer who was assigned to the nuclear torpedo, ordered him to assemble it to battle readiness. “Maybe the war has already started up there, while we are doing somersaults here”—screamed emotional Valentine Grigorievch [Savitsky], trying to justify his order. “We’re going to blast them now! We will die, but we will sink them all—we will not disgrace our Navy!”

Ultimately, cooler heads prevailed, Savitsky did not launch torpedoes, and the world was spared from the spark that likely would have triggered an apocalyptic nuclear war (see “Black Saturday Declassified,” June 2021, pp. 34–40).

After discussions with his second in command and the submarine’s political officer, Vasili Arkhipov, Savitsky made the decision to come to the surface. Upon surfacing B-59, he observed that one of the nearby destroyers had a jazz band playing on deck while the USS Cony (DDE-508) communicated by flashing light, inquiring if the submarine required assistance. Tongue-in-cheek communications between B-59 and her adversaries followed, with Savitsky identifying his submarine by different designations to each of the nearby U.S. destroyers.

B-59 apparently remained on the surface until the evening of 29 October, when the deck log of the U.S. destroyer Barry (DD-933) observed that the craft submerged “without warning.”

The Foxtrot B-36 was forced to surface after 36 continuous hours of sonar contact and harassment by the U.S. destroyer Charles P. Cecil (DDR-835) and maritime patrol aircraft on 30–31 October. The Cecil initially made contact with the surfaced submarine some 200 nautical miles north of Haiti on the night of 29 October. The submarine dived, but the Cecil, coordinating other surface ships as well as antisubmarine aircraft, held the contact until the submarine was forced up, apparently having depleted her battery after 36 hours of evasion efforts. The commanding officer of the destroyer, Commander Charles P. Rozier, subsequently was awarded the Navy Commendation Medal for maintaining contact during that period “despite repeated and extreme attempts by the submarine to escape.”

Upon surfacing, Captain Second Rank Dubivko of B-36 found helicopters hovering nearby and a signal light from the Cecil asking, “Do you need help?” Dubivko responded that he did not and asked that the U.S. forces not interfere with his actions.

The submarine/ASW aspects of the Cuban Missile Crisis provided the U.S. Navy with significant insight into Soviet submarine capabilities and tactics as well as problems. However, as the official U.S. analysis of the ASW operations—given the code name CUBEX, for Cuban Exercise—stated:

The reliability of results of CUBEX evaluation is affected by small sample size and biased by two major artificialities. The factitious aspects of the operation included the non-use of destructive ordnance and the priority scheduling of aircraft during daylight hours for the visual/photographic needs of the Cuban quarantine force. The unnatural case of not carrying a contact through to the kill affected the tactics of both the hunter and hunted, as did the unbalanced day/night coverage.14

The Soviet submarines sought to evade detection by short bursts of high speed, radical maneuvering—including backing down and stopping, taking advantage of thermal layers, turning into the wakes of ASW ships, and releasing “slugs” (bubbles) of air and acoustic decoys.

Knowing at times that they probably were safe from attack with lethal weapons, and not being required to carry out attacks against U.S. ships, the Soviet submarine captains were not realistically tested in a conflict situation. Also, the submarines made considerable use of radar, which they might not employ to the same extent in wartime. Extensive snorkeling also occurred, with durations of one-half hour to 11 hours being detected by U.S. forces. In a true wartime environment, the submarines would have conducted less frequent and shorter-duration snorkel operations.

Despite the “peacetime” environment, with large numbers of ASW ships and aircraft available, uninhibited communications, and the lack of counterattacks by their prey, U.S. antisubmarine forces were hard pressed to track down and force identification of the four Soviet submarines. The SOSUS seafloor detection system was available to U.S. forces but, according to a Navy after-action report, the “SOSUS signature library contents on USSR submarines are understandably meager. Further, the signatures [of Soviet submarines] were found to be significantly different from the expected.”15

During the crisis the Soviets made no effort to deploy their force of missile-armed submarines to within striking range of the continental United States. The four Soviet Foxtrot-class submarines that did operate in the Caribbean area during the crisis were harassed continually by U.S. naval forces following imposition of the quarantine. Being kept underwater—unable to snorkel—for days at a time exhausted their batteries, which meant that air was not being effectively circulated. And the submarines, built for northern waters, lacked air conditioning and were heavily insulated, leading to unbearable internal temperatures in the Caribbean waters. Also, in some submarines the carbon dioxide built up to dangerous levels as the boats were unable to draw in fresh air.

Despite the several confrontations, there were no U.S. attacks on Soviet submarines, nor did any of the Soviet submarines fire on U.S. warships—with either conventional or nuclear torpedoes. But it was a close-run “game”—sometimes referred to as “cat and mouse” by ASW practitioners, although that term was used more often by journalists than by naval officers.

The only “combat” death during the crisis was a U-2 spyplane pilot, Air Force Major Rudolf Anderson Jr. His aircraft was shot down over Cuba by a Soviet-launched surface-to-air missile on 27 October.

During the crisis the adrenalin was pumping in U.S. sailors on board destroyers and the pilots of ASW helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft as they sought the Soviet undersea craft. And the harassment was taking a great toll on the Soviet submariners. A sudden, unexpected maneuver by a destroyer captain, or the release of a decoy by a submarine believed to be a torpedo launch by a destroyer sonarman could have led to a deadly exchange.

Those tense moments of near-confrontation during the Cuban Missile Crisis were, quite properly, “the time of gravest concern” for President Kennedy—and for the world.16

1. Sergei N. Khrushchev, Nikita Khrushchev and the Creation of a Superpower (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University, 2000), 519.

2. William E. Knox, “Close-up of Khrushchev During a Crisis,” The New York Times Magazine, 18 November 1962, 32.

3. Ernest R. May and Philip D. Zelikow, The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House During the Cuban Missile Crisis (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), 353.

4. Robert F. Kennedy, Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis (New York: W. W. Norton, 1969), 69.

5. Kennedy, Thirteen Days, 69–70.

6. Khrushchev, Nikita Khrushchev, 566.

7. The West’s only nuclear torpedo was the U.S. Navy’s Mk-45 ASTOR (antisubmarine torpedo), operational from 1958 to 1977. It carried a W34 nuclear warhead rated at 11 kilotons.

8. Georgi Kostev interview with William Howard, Moscow, 18 June 2002.

9. Aleksey Dubivko interview with William Howard, Moscow, 18 June 2002.

10. Khrushchev, Nikita Khrushchev, 566.

11. May and Zelikow, The Kennedy Tapes, 356.

12. The Pamir subsequently was converted to an intelligence-collection ship and renamed the Peleng.

13. Alexander Mozgovoi, The Cuban Samba of the Quartet of Foxtrots: Soviet Submarines in the Caribbean Crisis of 1962 (Moscow: Military Parade, 2002).

14. Commander, Antisubmarine Warfare Force, U.S. Atlantic Fleet, to Chief of Naval Operations, Subj.: “Summary, Analysis and Evaluation of CUBEX,” ser 008187/43, 5 November 1963, I-3-1.

15. Deputy Chief of Naval Operations (Fleet Operations and Readiness), “Compilation of Lessons Learned/Deficiencies Noted as a Result of Cuban Operations,” Ser 00230P30, 20 February 1963, 19.

16. In Mark Rascovich’s book The Bedford Incident (1963) and the subsequent film of the same name starring Richard Widmark and Sidney Poitier, an exhausted U.S. sailor misunderstands a command and fires a rocket-assisted torpedo at a Soviet submarine; before it is destroyed, the submarine launches several nuclear torpedoes at the fictional USS Bedford.