The naval saga of the Cuban Missile Crisis is as bloodcurdling as it is instructive. The greatest sea story never heard lay submerged beneath a sea of bureaucratic subterfuge, labeled “Top Secret,” in the Soviet Union for 40 years.

Details of the “B-59 incident” seeped out like myths: a sailor’s letter home, an interview, a reunion, a document declassification. The voyage began on Kola Bay and ended beneath the Sargasso Sea. On board the submarine, an obscure, mid-level Russian officer from a peasant farm thwarted the launch of a nuclear torpedo—safeguarding mankind and preserving civilization. This is a tale to be remembered and to challenge historians to reconsider the essence of what the Russians call the Caribbean Crisis: The greatest hero of all was a Russian naval officer whom almost nobody knows, who stood steadfast amid the escalating international brinksmanship at one of the most perilous moments in modern history.

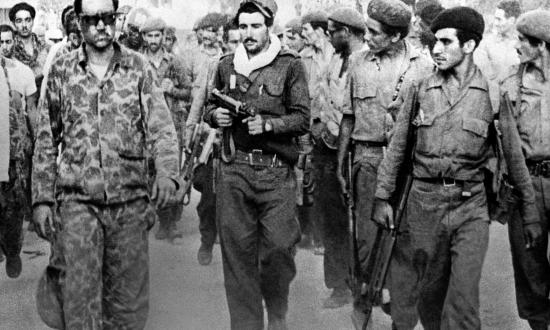

The Russians consider Operation Anadyr—the secret deployment into Cuba of nearly 40,000 combat troops, 100 tactical nuclear weapons, and 60 medium and intermediate ballistic missiles with megaton warheads—to be their greatest victory of information deception and denial. Kama, the naval contingent of Anadyr, called for establishing a Soviet submarine base in Mariel Bay, Cuba. Layers of maskirovka—Russian military deception—shrouded Anadyr from U.S. intelligence by keeping the Soviet participants, including ship captains, in the dark about their ultimate purpose. That purpose was twofold: to place the United States within easy reach of offensive nuclear weapons, and to repel an American invasion of Cuba with tactical nuclear weaponry, all with the blessing of Cuban leader Fidel Castro.

Nukes for Fidel

The operational plan for Anadyr was presented to the Chairman of the Soviet Defense Council and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev on 24 May 1962. The approved operation was taken to Castro, who agreed by 29 May. The date for completing the installations in Cuba was 27 October, the last Saturday of the month.1 Planning for Operation Kama was delegated to Vice Admiral Vitaly Fokin, First Deputy Commander in Chief of the Soviet Navy, second in charge to the Navy’s Supreme Commander, Fleet Admiral Sergei Gorshkov.

Admiral Fokin had four months to execute the deployment of the 20th Submarine Squadron of the Northern Fleet. He delivered his plan to the Defense Minister and Khrushchev on 18 September. It included the permanent deployment of four torpedo submarines, seven missile submarines, two cruisers, two missile ships, two destroyers, two submarine tenders, and a battalion of auxiliary ships, with a sail date of 7 October.2

One week later, Fokin revised the plan, reducing the force to the four diesel boats of the 69th Submarine Torpedo Brigade with a new sail date of 1 October. Chaos ensued. His plan included 21 conventional warheads and one nuclear torpedo warhead per submarine.3 After the mission briefing, the brigade commander suffered a massive hypertension attack. He was hospitalized and replaced by Captain First Rank Vasili Naumovich Agafonov 26 hours prior to sailing.4

At 0400 on 1 October, the brigade got under way, one by one, at 30-minute intervals, and fell into a dark, silent procession—B-59, B-36, B-130, and B-4. The diesel engines fired up after exiting Sayda Bay, where they had loaded torpedoes and Osnaz special forces commandos. The nukes lay in their cradles, sealed orders rested in their safes, as the boats sailed into the unknown.

U.S. antisubmarine warfare (ASW) forces were ready. The Norwegian Sea lies between the coasts of Norway and Greenland from the North Cape to the North Atlantic. The U.S. Navy had installed Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS) sensors in the deepest shallow spots, choke-point ridges on the seafloor. SOSUS cued Norwegian hydroplanes and intelligence ships—modified seal-hunting vessels stuffed with modern equipment, sponsored by the CIA and operated by American specialists—to detect and track Soviet submarines.

The 69th Submarine Torpedo Brigade eluded the Norwegians only to find the British searching for them—with more sophisticated Shackleton planes patrolling the sky like palace guards—as they emerged from the Norwegian Sea and hid among hundreds of fishing boats. U.S. P-2 Neptune ASW aircraft joined the search as the brigade passed over the submerged, sensor-laden ridge between Iceland and the Faroe Islands into the blustery North Atlantic. The Soviet captains opened their orders to find they were bound for Cuba, with no additional explanation.

Ships entering the North Atlantic are bound for heavy weather. Planes, ships, and radars could spot submarine sails and diesel plumes in fair weather. In rough seas, however, white-capped waves present a random patchwork to the naked eye or the radar screen, cluttering the senses with ghosting objects that disappear as they emerge in a kaleidoscope of sparkles. Diesel exhaust blows away, and a submarine sail appears as a smudge of flotsam or jetsam. However dangerous for the crews, heavy weather supported the mission as an ally—until it became the enemy. The 69th Torpedo Submarine Brigade crews suffered beatings, including broken ribs, from the rough seas.5

Communications with Moscow deteriorated as they sailed farther from their motherland. With information at a premium, the submarine captains discovered that some of their Osnaz riders spoke English and could monitor commercial radio broadcasts for news and weather. They learned that Hurricane Ella filled the gap between New York and Bermuda, and they had no choice but to ride it out. The storm scattered the U.S. fleet and damaged three of the four Soviet submarines. Only B-59 emerged unscathed as they approached the Sargasso Sea and the Bermuda Triangle.

Arctic Subs, Tropical Swelter

Seawater temperatures rose to 80 degrees. The heat off electronics, engines, and cooking surfaces built to 100 degrees, and the cold-water crews perspired until they soaked their socks. Nothing about the Arctic-insulated Foxtrot submarines was designed for operating in subtropical climates. The compartments within the boats began to swelter. The men who had suffered most in the heavy weather, who had lost too much weight and strength, began fainting from heat stroke. Mission-critical equipment redlined. Operators couldn’t service the gear without burning their hands. The temperature rose to 113 degrees forward, and 149 degrees in the engineering compartments. Refrigeration systems for the freezers, stocked with meat, not eaten due to the storms, failed. The cooling side of the desalinization plant faltered, and fresh water was in short supply.6

The submarine-turned-steambath gave everyone problems. Trench foot ran rampant, inflaming the soles of feet, rendering them swollen, supersensitive, and evil-smelling. With no ability to wash off dirt and sweat, everybody’s skin was covered in a rash. The desperate situation left most men feeling ill, weak, and unable to sleep in the monstrous heat and suffocating air. Limited reserves of fresh water permitted only one cup of water per man per day during prolonged periods of heavy sweating and dehydration.7

Crews surfaced to ventilate the boats only to discover the largest ASW force ever assembled in one ocean. By 20 October 1962, ASW aircraft squadrons and reconnaissance patrols were moving toward Florida. The nuclear-powered carrier USS Enterprise (CVN-65) left Norfolk, and the USS Independence (CV-62) and Randolph (CVS-15) scoured the Sargasso Sea with 40 other ships, including destroyer escorts and amphibious squadrons. Two ASW groups led by the USS Essex (CV-9) and Wasp (CVS-18) operated south of the brigade.

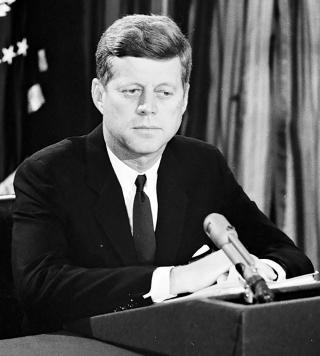

Moscow ordered the submarines to alter course and proceed to combat sectors in the South Sargasso Sea.8 They made an astonishing discovery. Inexplicably, every U.S. naval broadcast was in the clear: shore-based, ships, submarines, and patrol craft. They listened to voice chatter and read message traffic broadcasting operational movements in advance. They listened to President John F. Kennedy’s famous speech on 22 October announcing the U.S. discovery of Soviet missile sites and a quarantine to prevent further buildup of offensive weaponry. Moscow demanded that they maintain continuous communication in case of war. Maskirovka was over.

B-130 had three damaged diesel engines. B-4’s aft deck hatch was bent and leaking. B-36’s decoy ejector was leaking. B-59’s diesel cooling system was contaminated by saltwater, packing glands were leaking, and the electric air compressors had broken down. The Essex, Randolph, and Wasp swept the Sargasso Sea in reaction to a visual sighting of B-130 that set the U.S. Navy airways abuzz and ignited the launch of additional ASW aircraft. The Soviet brigade remained submerged as it was their only means to evade the waves of maritime patrol craft vectored onto their positions by SOSUS, but the boats needed oxygen and a battery charge. One of the Randolph’s S2F (S-2) Trackers laid sonobuoys despite the stormy, extreme blackness. In the wee hours of 27 October, the Tracker detected B-59. The chase was on.

‘One Step Shy of War’

27 October 1962—Black Saturday, as it came to be known—shaped up to be a horrifying day in terms of a potential nuclear apocalypse under Defense Condition Two, one step shy of war. The Strategic Air Command readied 5,500 bundles of nuclear wrath for the enemy, with nearly 3,000 nuclear warheads aimed at 1,000 targets in the Soviet Union. The United States tested two nuclear weapons that day: a ground explosion at the Nevada Test Site, viewed by thousands of dancing tourists quaffing “atomic cocktails” at blast parties along the Las Vegas Strip, and a lesser-known atmospheric detonation over remote Johnston Atoll, in the Pacific west of Hawaii. The Soviets, meanwhile, air-dropped 262 kilotons on their Arctic test site at Novaya Zemlya.

The CIA reported that five Soviet R-12 nuclear ballistic missile sites in Cuba appeared fully operational. A U-2 pilot, U.S. Air Force Major Rudolf Anderson Jr., flew at 70,500 feet over Cuba to photograph Soviet missiles near Guantánamo Bay. Two Russian surface-to-air missiles, fired from Cuba, exploded. Shrapnel punctured Anderson’s cockpit and pressure suit. His lungs ruptured under violent decompression and formed a pink cloud that shot through the windshield of his disintegrating Dragon Lady at half the speed of sound. The remains of his body, strapped to the remnants of his plane, crashed on Cuban soil. His mission was so secret, he did not exist except as a lost radar contact.

Every attempt to rejuvenate B-59’s overheated batteries attracted ASW overflights. An ear-shattering explosion reverberated through the boat. With little reserve power, she could neither run nor hide. After five hours of catch and release, the USS Beale (DD-471) and Cony (DD-508) gained solid sonar contact on B-59, and Trackers continued to swarm and drop echo-ranging depth bombs and practice depth charges. The USS Murray (DDE-576) maintained contact with constant pinging for four straight hours throughout the chase. On board the submarine, the blasts could not be distinguished from tactical depth bomb explosions.

The air on board B-59 was low on oxygen and saturated with toxic carbon dioxide, hydrogen, and methane, driving the crew into hypoxia, lethargy, and confusion. The Admiralty’s instructions were boxing in the submarine’s commander, Captain Valentin Savitsky, limiting his maneuverability, forcing him to expose his position at the surface, waiting for signals that never came. His men were lying about the boat in grimy underwear, quivering with cramps. Eighteen hours of agonizing submergence in a steel tank, culminated in an ominous hail of subaquatic grenades. One hour of battery life remained. The time left to fight drained away like sand in an hourglass, and oxygen deprivation closed in. Depth charges exploded with spectacular power and proximity like hundred-knuckled fists, damaging radio antennae two meters above their heads.

Captain Savitsky lost his composure in the asphyxiating madness: “The war has already started up there, and we are down here doing somersaults.” He believed that war had broken out, and his instructions had been to use the nuclear weapon first. He screamed: “We’re going to blast them now. We’ll die, but we will sink them all. We won’t disgrace our Navy or shame the fleet.”9

A Cooler Head Prevails

Vasili Arkhipov, the brigade chief of staff, experienced a moment of clarity. He perceived that there was no war. The Americans wouldn’t waste their substantial resources fixating on a diesel submarine if a full-blown war had broken out. They either would kill the sub or abandon it without a second thought. He realized that a nuclear attack on a U.S. carrier could unleash immediate, all-out nuclear insanity around the globe. He convinced Captain Savitsky to order a single sonar ping to test the Americans’ intention.10

Their own ping rang through the hull, and when it died away, they listened: thunderous, ear-splitting, wondrous silence. Sonar reported ranges and bearings to the three destroyers and indicated that they simultaneously had come to full stop.

When B-59 surfaced, blue-white lights from the Cony made it impossible to see. The Murray blared wild jazz music in the blackness. The music yielded to the roar of S2F (S-2) Trackers jettisoning brilliant white phosphorous to activate photoelectric camera lenses, as 50-million-candlepower incendiary devices exploded above their heads.

Captain Savitsky sent a message: “This ship belongs to the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Halt your provocative actions.” He received an apology. It was over.

Ironically, at the same moment, the White House and the Kremlin acknowledged the civilization-ending consequences of a nuclear cataclysm and agreed that nuclear war was not a viable option, given the devastating consequences for humanity.

Had Captain Second Rank Vasili Arkhipov not intervened, a nuclear blast could have erupted in the Sargasso Sea, vaporizing the Randolph’s Task Group Alpha. President Kennedy had announced only five days earlier, “It shall be the policy of this nation to regard any nuclear missile launched from Cuba against any nation in the Western Hemisphere as an attack by the Soviet Union on the United States, requiring a full retaliatory response upon the Soviet Union.”

Amid the U.S. naval aggression against B-59, Arkhipov sorted through the chaos at the moment of decision: shoot to kill, or surface the submarine and surrender. His choice, his very existence, was lost to history until the Soviet Union collapsed. Fidel Castro held a conference in Havana in 2002, on the 40th anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis. The truth was revealed.

In London on 27 October 2017, the 55th anniversary of Black Saturday, the Future of Life Institute honored Vasili Arkhipov with its inaugural Future of Life award, the first public appreciation of his contribution to society.11 The posthumous recognition was accepted by his daughter, Yelena Andriukova, and his grandson, Sergei Andriukova, on behalf of Arkhipov, who “never said a word to his family because it was closed, secret information—he wasn’t allowed to talk about it.” Arkhipov seemed to have understood that nuclear warfare is simultaneously instantaneous and everlasting.

Christmas in Confinement

The brigade made its way back to Kola Bay through the heavy weather of the North Atlantic, the ASW choke points, and snow squalls in the Norwegian Sea. B-130 was under tow. B-36 had lost fuel and damaged diesel engines as a result of human error. B-4’s bent hatch continued to leak. B-59 made port in the predawn hours of Christmas Eve as B-36 rounded North Cape to arrive late on Christmas Day. They limped home in frigid weather and emerged from the boat exhausted, emaciated, hypothermic, infected, and filthy, only to find themselves under security restriction in a raging blizzard. The only man to meet B-36 with Christmas wishes was the brigade chief of staff—the unsung hero of whole international incident, Vasili Arkhipov.

There was no roast pig, no brass band, no parade drums, and no vodka as was customary for a Russian sub returning from an arduous mission. Rear Admiral Leonid Rybalko, the squadron commander, confined officers and crews to their boats, pending a full investigation of how they disobeyed orders to remain covert and undetected. It mattered not. They had made it home, and the admiral’s wife had personally parlayed enough green salad, sardines, pickled herring, and cow’s tongue into a platter of zakuski to fill their shrunken bellies. Military guards cordoned off the pier, holding them prisoner on their boats as the Christmas blizzard buried them in snow. They were not allowed to mingle with or speak to the other crews. It was December in Sayda Bay, the time of darkness when the days are mostly night. The investigation could begin.

There were investigations into disobedience and mission failure. Brigade Commander Vitaly Agafonov was promoted to admiral and assigned to the nuclear submarine fleet. Captain Ryurik Ketov was promoted to command of a nuclear submarine. They had commanded B-4, which never had been forced to the surface. Agafonov, Ketov, Captain Nikolao Shumkov of B-130, Captain Aleksei Dubivko of B-36, and Osnaz Lieutenant Vadim Orlov lived to tell their tales of the journey. Admiral Rybalko was relieved of his command, forced into retirement, and never seen again. Captain Savitsky disappeared. These things happened in the Soviet Union.

And Captain Second Rank Vasili Arkhipov, the man who saved the world from a nuclear holocaust? He never spoke of the voyage.

1. Anatoli Gribkov and William Y. Smith, Operation Anadyr: U.S. and Soviet Generals Recount the Cuban Missile Crisis (Chicago: Edition Q, 1994).

2. Vitali A. Fokin and Matvei V. Zakharov, Initial Report of Soviet Naval Activities in Support of Operation Anadyr, 18 September 1962, “Top Secret of Special Importance for Premier Khrushchev,” translated by Gary Goldberg.

3. Vitali A. Fokin and Matvei V. Zakharov, Report on Progress of Operation Anadyr, 25 September 1962, “Top Secret of Special Importance for Premier Khrushchev,” translated by Gary Goldberg.

4. Peter A. Huchthausen, October Fury (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2003).

5. Huchthausen, October Fury.

6. Captain First Rank Ryurik A. Ketov, Russian Navy (Ret.). “The Cuban Missile Crisis as Seen Through a Periscope,” Journal of Strategic Studies 28, no. 2 (2005): 217–31.

7. Ketov, “Cuban Missile Crisis as Seen Through a Periscope.”

8. Ketov.

9. Alexander Mozgovoi, “The Cuban Samba of the Quartet of Foxtrots: Soviet Submarines in the Caribbean Crisis of 1962,” Military Parade, Moscow, 2002.

10. Mozgovoi, “Cuban Samba.”

11. “The Future of Life Award 2017: Celebrating the Contributions of Vasily Arkhipov,” Future of Life Foundation.