Remember the Maine? We might be Spain. In 1898, the rising industrial power of the United States fought the Spanish Empire, then already straining under its global commitments. The war started in part over questions of independence on an island dozens of miles from the U.S. coast—Cuba. A deliberate disinformation campaign following a naval incident exacerbated enduring tensions. Party pressure and public outcry forced President William McKinley to intervene. The U.S. Navy, having been built up in a generation from a coastal defense force to near blue-water dominance, isolated the global power and blockaded Cuba. Suing for peace mere months after numerous defeats, the war shattered the Spanish Empire, while the Navy secured its regional ambitions and set the course for global dominance into the next century.

The Spanish-American War and the U.S. Navy’s Caribbean campaign are not frequently cited for their historical similarity to 21st-century great power competition. Conceptually, too, blockades appear inefficient and obsolete in the age of missile warfare. Yet, three critical actions during the Cuban blockade present stark examples for modern-day peer conflict around Taiwan and U.S. Pacific naval bases: the Raid on Cienfuegos, the sinking of the Merrimac, and the Battle of Santiago de Cuba. Taken together, the Navy limited Spanish operational communications, denied the Spanish Navy’s freedom of maneuver, and destroyed its ships attempting to escape the harbor. Modern Chinese analogies to these blockading actions abound, from the destruction of submarine cables to scuttling Chinese containerships to a discriminate, open blockade of U.S. naval bases in the western Pacific. The Navy must think, invest, and train now to break a modern blockade. Planning for blue-water victory assumes the fleet left port safely in the first place.

In 1898, it was the U.S. Navy that sought a closed blockade around Cuba to choke off Spanish resistance. Two days after the U.S. declaration of war against Spain on 21 April 1898, Rear Admiral William T. Sampson, commander of the North Atlantic Squadron, commenced implementation of a blockade against the western half of Cuba’s northern coast. Sampson’s initial squadron consisted of 26 ships, leaving his blockade perilously thin to avoid both Spanish resupply from Mexico and Central America, as well as the expected arrival of a Spanish Navy squadron from Europe. The initial focus was to close Havana Harbor, and Sampson interdicted contraband goods while fighting minor skirmishes and supporting Marine Corps and Army amphibious operations onto the island. Atlantic Fleet’s 4th Division, a flotilla of five ships, was tasked to blockade the southern half of Cuba, namely the port of Cienfuegos. It was on the beaches of this south-central Cuban seaport that a Navy–Marine Corps team of junior officers, sailors, and Marines would gallantly seek to isolate the island from Spanish mainland communications.

The Raid on Cienfuegos and Today’s Submarine Cables

Cienfuegos served as the key junction for the submarine telegraph cables laid between Cuba and Spain. Cutting them would sever communications between Spanish loyalists and their mainland commanders. The ragtag 4th Division included the cruiser Marblehead, the gunboat Nashville, the converted yacht Eagle, the revenue cutter Windom, and the collier Saturn, all under the immediate command of the senior officer present, Commander B. H. McCalla.

On the morning of 11 May 1898, Lieutenant Cameron Winslow of the Marblehead led a four-boat expedition consisting of a mix of Navy ratings as well as a Marine sergeant and six privates. Under supporting bombardment from Marblehead and Nashville, the small boats sailed in with cable-cutting tools consisting of hammers, chisels, pliers, a hacksaw, and grapnels to catch and bring the cables up from the beach. As the boats approached within 100 feet of the shoreline, Spanish shore batteries opened fire, increasingly accurate as the teams struggled to find and cut the different cables buried in sand and coral and battered by the sea.

For more than an hour the team worked under fire from the shore before retreating to the safety of Marblehead and Nashville, having cut three of the four major cables but leaving two dead and 15 sailors and Marines wounded. For their “example of extraordinary bravery and coolness under fire,” 52 sailors and Marines were awarded the Medal of Honor for the Cienfuegos cable-cutting mission. While its bravery and ingenuity once dealt Spanish operational communications a serious blow, the Navy must consider the risks of a similar attack on U.S. Pacific bases by the People’s Liberation Army–Navy (PLAN).

Today, submarine fiber optic cables transfer up to 99 percent of all internet data between continents, with the remaining amount completed by satellites. Fiber optic cable locations are well documented to avoid accidental damage, even if they are buried under the sand. While China is largely landlocked, the United States relies on numerous islands or archipelagos to forward deploy joint forces, including established bases in Guam, Okinawa, and Hawaii. Each of these Pacific islands supports critical command, control, and combat capabilities, with Oahu the headquarters for Indo-Pacific Command, Pacific Fleet, Pacific Air Forces, and the Naval Computer and Telecommunications Area Master Station Pacific (NCTAMS-PAC), among other commands.

At the outset of peer conflict, China could seek to cut the same types of cables as the Navy did at Cienfuegos. Each of these islands has limited cable connections traveling east or west to Japan, Australia, or the United States, as well as even fewer junction landing points. Guam has ten cables and four landing points; Okinawa six cables and three landing points; and for the Hawaii archipelago, eight cables and six landing points. Taiwan also has only four landing points, and could expect the same treatment. Each provides critical network services to the islands and is owned by commercial companies. At the outset of a Sino-U.S. conflict, the PLAN submarines, spy ships, or People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM) could launch unmanned underwater vehicles in international waters to destroy these cables. If coordinated with major cyber or antisatellite attacks, China could leave major operational headquarters of any Indo-Pacific response near dumb and blind to a rapidly evolving crisis.

While cyber defense is ongoing across numerous agencies and commands, the Navy has retained limited organic submarine cable repair capability. The USNS Zeus (T-ARC-7) is the single purpose-built cable ship under Military Sealift Command, and, at 37 years old remains, stationed in Norfolk to perform maintenance on the Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS) in the Atlantic Ocean. Even if reliable commercial cable-repair capacity existed in Guam, Okinawa, and Hawaii, it would take days or weeks for either the Zeus or another ship to transit to each point of cable damage, repair it, and restore the standard operating bandwidth to combatant and fleet commanders. Congress has raised these concerns, and the Navy recently released the award to research the next variant of the class, with an eventual goal of two in the fleet to be built in 2023 and 2024.These ships (or standing relationships with commercial cable repair ships) cannot be fielded soon enough in the Pacific as a ready reserve against a unique and historically similar strike against U.S. command and control.

The Sinking of the Merrimac and Scuttled Sino Container Ships

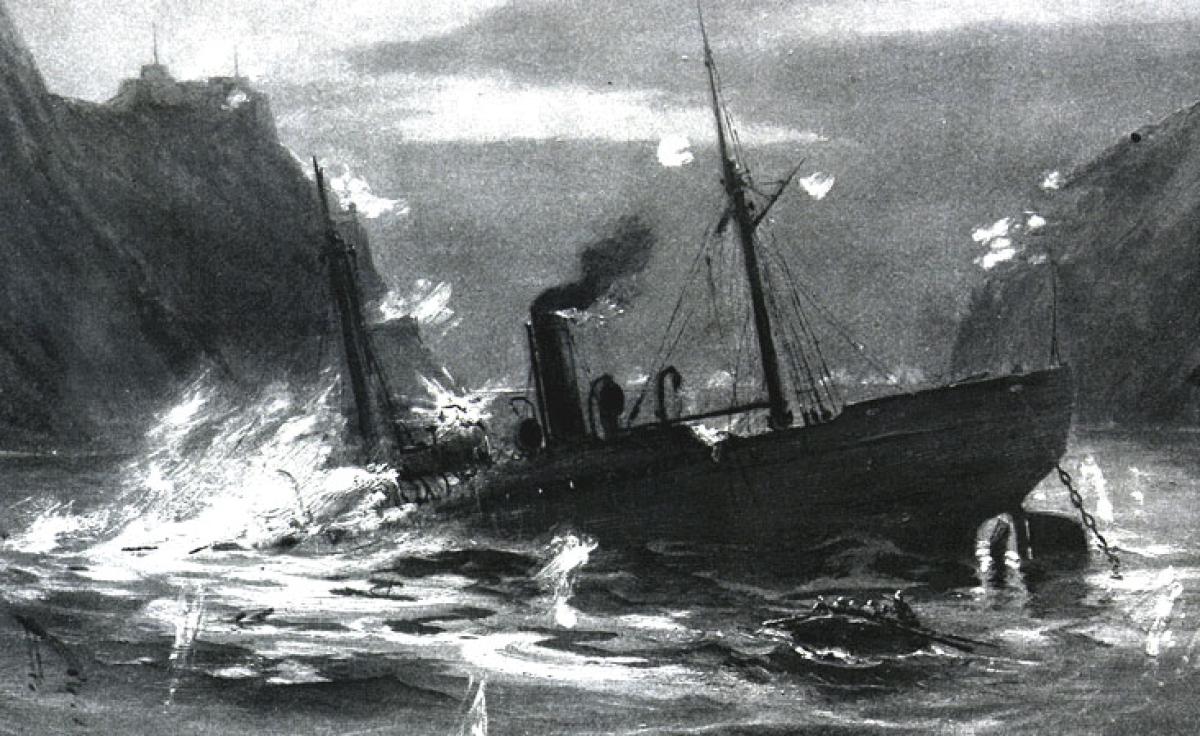

The second Spanish-American blockade action with modern implications is the sinking of the USS Merrimac on 2 June 1898. A month earlier, Spanish Admiral Pascual Cervera y Topete led the Spanish Caribbean Squadron of six ships across the Atlantic, ultimately evading U.S. fleet action and entering the harbor of Santiago de Cuba on 29 May. After sighting his cruiser Cristóbal Colón entering, the U.S. Navy commenced a closed blockade outside the mouth of the channel. Within days, Rear Admiral Sampson would arrive off Santiago in his flagship USS New York. Sampson tasked a naval constructor (the precursor of engineering duty officers) Lieutenant Richmond P. Hobson with a special mission: sink the collier Merrimac in Santiago de Cuba’s channel. Scuttling the old and crippled coal carrier would serve as a blockship and leave the Spanish Caribbean Squadron trapped.

Before the war, Sampson had served in the Bureau of Ordnance and thus took a direct role in developing the ten torpedoes [mines], each containing 78 pounds of cordite, to be strapped on the outside of the collier. Hobson selected six volunteers from the New York and Merrimac, and a seventh, Coxswain Claus K. R. Clausen, would eventually stowaway on board before the collier sailed away from the blockade. Despite departing for the harbor before dawn, Spanish shore batteries sighted the Merrimac, opening fire and disabling her steering gear before the ship was scuttled at the appropriate place in the harbor. All eight men of the Merrimac were taken as prisoners of war, and later awarded Medals of Honor for the “extraordinary courage [for] carr[ying] out this operation at risk of [their] own personal safety.” Hobson would go on to become a hero while a Spanish prisoner of war, with a future as a Victorian sex symbol, Alabama congressman, and best friend of Nikola Tesla. However, despite the failure of the unique blockship mission from the 19th-century blockade, today’s Navy must consider the possibility of a similar Sino-centric mission in U.S. harbors.

Using blockships as part of a blockade is not an antiquated tactic. The Russian Navy in 2014 towed and scuttled the decommissioned Kara-class cruiser Ochakov and rescue/diving support ship BM-416 at the entrance to Donuzlav Bay in western Crimea to prevent further Ukrainian Navy ships from leaving port. A Chinese blockship mission could be far more damaging. Given China’s well-known commercial shipbuilding capacity, if it believed war was approaching, it could conceivably take control of a collection of container ships bound for Hawaii and the U.S. West Coast. While all might appear well on the automated information system or ship manifests, a civilian-military crew like Hobson’s of 1898 could divert the Chinese containerships from their scheduled entrances into the commercial harbors of San Diego, Los Angeles, Seattle, and Pearl Harbor. Through nothing but deception and deliberate ship-driving, Chinese captains could scuttle their ships in the military or dual-use channels in San Diego, Seal Beach, Everett or Bremerton, and Pearl Harbor.

A fully loaded container ship rated for each of these scheduled commercial ports could carry up to 10,000 twenty-foot equivalent unit (TEU) containers. While not a blockade in the doctrinal sense, successfully scuttling the ship and dispersing even a fraction of those containers would create havoc for port security and the fleet’s freedom of maneuver—simpler and more effective than a textbook closed blockade. It likely would take weeks for harbor cranes and mobile diving and salvage units to remove each container and clear the wreckage, potentially leaving many Third Fleet ships in port.

To avoid the risk of similar asymmetric attacks on harbors, the Navy must continue to maintain vigilance in monitoring vessels of interest around critical harbors. Further, Congress should invest in additional crane, salvage, and security capacity across Navy, Coast Guard, and civilian authorities to ensure similar blockship attacks would be stopped far short of critical waterways. Yet should the United States find itself under threat of blockade beyond a blockship, it must think and act unconventionally to break it.

Cervera’s Dilemma and Breaking Modern Blockades

As the summer of 1898 progressed, U.S. Army attacks on Cuba increasingly constricted Spanish forces. On 1 July 1898, Colonel Theodore Roosevelt would lead the “Rough Riders” against Spanish Garrisons in the vicinity of Santiago in the Battle of San Juan Hill. Yet, the Army’s failure to take Santiago and instead start a siege of the city “produced consternation in Havana.”

Commander of Spanish forces in Cuba Governor-General Ramón Blanco ordered Spanish Admiral Pascual Cervera to sortie his squadron out of the blockaded harbor and flee to Cienfuegos. Cervera knew his fleet was outgunned, poorly trained, and in need of repair compared with Sampson’s blockade force, yet Governor-General Blanco was adamant the Army not capture Spanish ships in port. Cervera also decided to “attempt the breakout at first light on 3 July for three reasons: first, it was difficult to navigate the narrow entrance to Santiago de Cuba harbor at night; second, the American fleet was spread over a wider area during the day; and third, Cervera believed it would be easier to rescue his sailors in the event of a disaster.”

Once exiting the harbor, Cervera planned for the Spanish cruiser Infanta Maria Teresa to ram and disable the fastest U.S. cruiser, the USS Brooklyn, to distract the rest of the Navy blockade while the Spanish escaped. No Spanish ship escaped. The Navy resoundingly defeated the Spanish at Santiago de Cuba, with 1 American killed and wounded, whereas the Spanish suffered 343 killed, 151 wounded, 1,889 captured, and four armored cruisers and two destroyers sunk. Cervera, unsurprised, wrote to Governor-General Blanco after the battle: “The result was not doubtful to me, although I at times had thought that our destruction would not be so rapid.” This was the culminating defeat for the Spanish in the war, having already been defeated in the Pacific by Admiral George Dewey in the Battle of Manila Bay. Yet, the Spanish defeat also offers lasting lessons for the modern Navy in a future peer conflict.

Apart from the terrorist attack on the USS Cole (DDG-67) in October 2000, the Navy has not suffered any attack on a ship in a harbor since World War II, and today gets underway as a matter of routine. That includes common pre-underway systems checks, which are meant to test engineering and combat systems for their readiness for sea. While well-meaning and prudent in peacetime, at the outset of a peer conflict, these tests, and the routine process of getting underway, represent a critical security risk.

While the PLA increasingly modernized its antiaccess/area-denial (A2/AD) capabilities over the past generation, the Chinese also have invested in a web of supporting space-based sensors for intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, and targeting (ISRT). Nearly every time the U.S. Navy gets underway, its ships broadcast radar and communication signals across the electromagnetic spectrum at a regular interval in the days and hours approaching underway. In a hypothetical scenario at the outset of a conflict that has not broken out into open war, PLAN ships or submarines could operate far outside U.S. waters in the western Pacific, receiving space-based tipping and cueing to ships readying for underway. Open-source websites already record ships leaving port, as could synthetic aperture radar (SAR) imagery, or simple visual imagery. Given modern technology, it would be far harder for any fleet to break a blockade and proceed to sea.

How could the Navy escape port, if the PLAN is attempting a distant blockade enforced with space-based sensors and long-range antiship missiles? By practicing and preparing for Cervera’s dilemma. Instead of a routine 0800 Monday underway with two tugs and all pre-underways complete, Navy ships and submarines should practice promptly getting underway at night, with a single tug, in a strict emissions control (EMCON) posture before and during the underway. EMCON, nighttime, and promptness would help combat different types of space-based collection capabilities. Further, a single tug may be all that is available if an entire fleet must sortie out of the harbor, and while these scenarios are practiced in Newport simulators, they are untested absent emergencies today.

To build up to these competencies, each part-task should be practiced, starting with a planned night underway, to a transit with simulated radars secured, to more regular single tug operations, to a multiship prompt sortie. If a great power war appeared likely, and PLAN combatants lurked over the horizon in weapons release range to U.S. ports, the Pacific Fleet would do well to know how long it would take to get all ships to sea. Once at sea, the U.S. fleet could disaggregate before testing its external emissions sensors and weapons, in preparation for combat in distributed maritime operations. Strong consideration should be given to thinking and practicing as though U.S. ports are not always safe harbors, rather than naively assuming Chinese combatants would never seek to threaten them.

The Spanish-American War bears many conceptual resemblances to a future Sino-American conflict. While U.S. motives for Cuban independence are fundamentally different than the Chinese Communist Party’s desire to return Taiwan to Beijing’s control, in both cases, global powers were forced to fight across oceans in an industrial power’s region of concern. The heroism on the shores of Cienfuegos, on board the Merrimac, and in the littorals of Santiago is worthy of retelling not only for its junior leadership, Navy–Marine Corps ingenuity, and coolness in the face of fire. The Sea Services must humbly remember its forebearers in the eyes of its peer competitors, who have a far longer historical memory, and could seek to isolate U.S. power in the same ways at the outset of a conflict.

U.S. transatlantic cables, ports, and harbors have long been safely kept and otherwise ignored as critical but ultimately uninteresting infrastructure. It is in that mission-criticality that the Navy must prepare to repair its submarine cables, deny scuttled blockships, and break out from modern blockades. Only once the Navy is free to maneuver can it start to fight as it desires. Failure to be aware of and break future blockades may leave the fleet in port and idly watching history happen, just over the horizon.