Because the Civil War was primarily a land conflict, the crucial role played by navies—on both sides, but especially on the Union side—is often underappreciated. The battles of Bull Run, Shiloh, and Gettysburg became icons of U.S. history, as they should, given that during the war more than three million Americans fought one another across a thousand-mile front for four years. However, while the Union Army almost certainly would have emerged victorious as long as the Northern public sustained President Abraham Lincoln’s war policy, the Union Navy did affect the trajectory as well as the length of the war and had a significant impact on the cultural consequences.

Scholars often point out that the Civil War took place during a time of dramatic, even revolutionary, technological change. Indeed, one of the things that makes the war so fascinating is that it straddled a period during which the character of war itself manifested both the romantic imaginings of Sir Walter Scott as well as the bitter realities later described by Erich Maria Remarque. It was both highly personal and horribly efficient, and this was in part because of the extended range and accuracy of the rifled musket and the minie ball.

It was an era of technological change at sea, too. Civil War navies included steam warships, many of them driven by screw propellers. Some of those warships were protected by iron armor. They were armed with rifled cannon of unprecedented size and capability that fired explosive shells as well as iron shot. They included both the ironclad USS Monitor with her iconic revolving turret, and the Confederate H. L. Hunley, the first submarine to sink an enemy warship at sea. And all of this created a new template for naval war, one to which the officers and men had to adjust.

Officers who had spent 20 or 30 years in what was even then called the “Old Navy” had to learn about navigating under steam, the logistics of coaling, the capacity of the new naval ordnance, the changing relationship between ships and forts, and the threat of underwater mines or torpedoes. Then, too, the expansion of the Navy accelerated promotions dizzyingly. Men who had served for decades as lieutenants on sailing ships deployed to distant patrol suddenly became captains in charge of whole squadrons of steamships, their wardrooms occupied in many cases by “acting volunteer lieutenants” from the merchant fleet or fishing boats.

There was a revolution belowdecks as well. The few thousand old tars who had manned the sailing ships of the Navy in the 1840s and ʼ50s were now augmented by more than a hundred thousand volunteers, many of whom had never seen the ocean. Some were motivated by patriotism, some by the call of adventure, and some merely sought to avoid the first draft in U.S. history. They were farm boys and mechanics, clerks and students. Still others were so-called contrabands—essentially, escaped slaves—who rowed out from “the Rebel coast” and volunteered to serve. The U.S. Navy always had encouraged enlistment by black Americans—indeed by any able-bodied individual who could pull a rope or swab a deck—yet the shifting demographic on board ship challenged many of the hoary traditions of the sea.

The full story of the two navies’ role in the Civil War requires a book, of which there are several, including those listed at the end of this article, but three aspects of the naval war are especially pertinent in understanding the conflict: the Union blockade, the Confederate commerce raiders, and Union joint Army-Navy efforts to control both the Confederate coastline and the Western rivers.

The biggest assignment of the Union Navy in the Civil War was the establishment and maintenance of a blockade of the Southern coast. It was, in fact, the largest naval undertaking in all of U.S. history until World War I, absorbing more ships and more men than all other naval operations combined. By 1865, it included more men and more ships than had served in all of America’s previous wars.

The idea of imposing a blockade on one’s foe was hardly new, but it was new for the United States, which, in its wars with England, was more likely to be blockaded than to blockade. Yet, it was practically the first strategic decision made by the Lincoln administration after the surrender of Fort Sumter. Some have characterized Lincoln’s proclamation of a blockade on 19 April 1861 as a mistake, the result of his meager understanding of international law. To be sure, Lincoln faced unprecedented problems in 1861, and in response to many of them he simply had to make it up as he went along.

Even so, the President was not completely adrift in dealing with the legal nuances of a blockade. He knew that a blockade was an act of war and that it likely would be perceived in some quarters as a recognition of the Confederacy as a belligerent, if not as a nation. Both Secretary of State William Seward and Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles suggested that, instead of a blockade, Lincoln could simply announce that he was closing certain ports. U.S. Navy warships and revenue cutters would be stationed off these ports to redirect merchant shipping to other ports that remained open.

Alas, the mere closing of ports would not authorize U.S. ships to patrol over the horizon, or to stop suspicious vessels along the coast. In the end, Lincoln decided he had to accept the term “blockade,” whatever it might imply about the legality of the Confederacy.

Of course, declaring a blockade was one thing, making it stick was another. According to the Declaration of Paris of 1856, a blockade was not binding on neutrals unless the declaring power maintained an effective force off every port that was declared to be blockaded. That meant the Union had to position a naval force off every one of the 189 entry ports along the 3,500-mile coast of the self-proclaimed Confederacy. Since the U.S. Navy had only some 42 ships on active service, Lincoln’s declaration provoked skepticism and even ridicule both in the South and in European capitals. The initial task, therefore, was to dramatically expand the size of the Navy.

The first steps in the expansion were to ready the warships laid up in ordinary, bring home those from overseas, and add 23 new purpose-built gunboats (the original 90-day wonders). That gave the Union Navy a total of more than 100 warships, most of them steamers. Yet, that was still only a fraction of what was needed. Most of the rest—eventually more than 500 ships—came from converting merchant steamers to wartime use. For the most part, these were the ships that established and maintained the blockade.

Blockading was tedious work. Day after day—often week after week—passed with no sign of a vessel trying to run into port, or one in port seeking to escape. A word commonly used by sailors writing home to their families was “tedium.” Night was the most perilous time. In the middle of a moonless night, or perhaps in a misting rain, a lookout might perceive a slightly darker shadow amid the blackness; a rocket would be fired into the night sky to alert the rest of the squadron; adrenaline pumping, men would stumble up from below to cast loose the big guns and train them out into the darkness; muzzle flashes would light up the night temporarily blinding the gunners. Some of the Union blockading ships might slip their anchors and set out in pursuit. And then, as suddenly as it began, it was over, more often than not with the blockade-runner escaped, the men angry about their missed opportunity, and the officers frustrated.

Scholars have argued for decades about the relative value of maintaining such a porous blockade. On one hand, studies have demonstrated that the Confederacy managed to import enough rifles and cannon, powder and lead, and other essential materials of war to sustain its armies. Some have suggested that this was proof the blockade was not a significant contributor to Union victory. On the other hand, if it did not completely seal off the Confederacy from the outside world, it did have a gradual asphyxiating impact on the whole Southern economy. In the first 18 months of the war, the number of vessels going in or out of Southern ports declined by 90 percent, and that profoundly affected the South’s overall economic health, contributed to declining civilian morale, and weakened Southern resolve.

If maintaining the blockade was the principal naval strategy of the North, the South embraced the default naval strategy of the weaker power: commerce raiding. Often referred to by its French name, guerre de course, it had been the principal naval strategy of the United States in both the American Revolution and the War of 1812. It would be used as well by Germany in the Atlantic and by the United States in the Pacific in the 20th century.

Much of the commerce raiding in America’s earlier wars had been conducted by privateers—small, privately owned, and usually lightly armed ships. Privateering had much to recommend it: It cost the host government nothing but a piece of paper—a letter of marque—allowing the possessor to capture, burn, or destroy ships of the enemy. Although privateering had been outlawed by an international convention in 1856, the United States had refused to sign the protocol, a fact that Confederate President Jefferson Davis noted in issuing a call for Confederate privateers even before Lincoln announced the blockade.

The problem for Davis and the Confederacy was that privateering depended entirely on the profit motive, and without ports where privateers could send their prizes, they could not profit from their efforts. As a result, Confederate privateering dried up in just a few months, as would-be privateers turned to blockade-running as both safer and more profitable. That did not mean the South gave up on guerre de course, but it did mean that Confederate commerce raiding had to be carried out by commissioned Confederate Navy warships.

Of course, at the outset of the war, the Confederacy had no navy, and so to obtain commerce raiders, it sought to acquire ships abroad, particularly from England. The most famous of them was the CSS Alabama, built in the Birkenhead shipyards on the Mersey River, opposite Liverpool, and commanded by Captain Raphael Semmes. During a two-year cruise over three oceans, Semmes and the Alabama captured 64 Union ships and sank one warship: the unlucky USS Hatteras—the first time in history that a steam warship sank another steam warship.

Semmes and his crew did not get rich from their captures. Since he could not send the ships into a friendly port to be condemned, he simply burned them. There was some grumbling about that, not only in Northern newspapers but also among the Alabama’s crew. Though the Alabama’s officers were Southerners like Semmes, the crew was international—British, French, Portuguese, Dutch, and others—and they were in it for the money. Semmes had promised them the Confederate government would pay them prize money for every ship they burned, but, of course, that could happen only after—and, most importantly, if—the Confederacy won the war, which became less certain as time passed. In fact, the crews of Confederate raiders never did get any serious prize money, though interestingly, that did not deter the crew of the Alabama from accepting battle with the USS Kearsarge off the coast of France in June of 1864—the battle that finally ended the Alabama’s rampage. Collectively, raiders such as the Alabama caught and destroyed a total of 284 Union merchant ships during the war.

There also were secondary costs to the Union beyond the immediate loss of those 284 ships. Because of the threat of the raiders, Union shippers had to pay much higher maritime insurance rates, and some shipowners reflagged their ships as French, Belgian, or Danish to avoid being targeted. The rampages of these Rebel raiders also triggered political pressure on the Lincoln administration to do something about it, and Secretary Welles sent out what a later generation would call hunter-killer groups to track them down. The bottom line was that the Confederate raiders produced a reaction quite disproportionate to their numbers.

They did not, however, bring the Lincoln administration to the negotiating table; they did not compel Welles to weaken the blockade; and they did not retard the Union war effort on land. The best chance the South had to achieve its independence was not to “win” the war in any conventional sense. Rather, it was to wear out the political will of the Northern population to sustain Lincoln’s war policy. An effective war on commerce was an important part of that effort. That in the end it did not work says much about Lincoln’s determination and the willingness of the Northern public to sustain him.

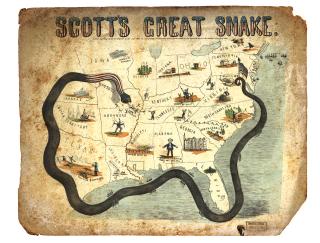

Joint operations, especially along the Confederate coast and on the inland rivers, were another important part of the naval war. From the beginning, Union planners had envisioned a campaign to seize control of the Mississippi River—part of the famous Anaconda Plan devised by Union Army Lieutenant General Winfield Scott. It would divide the Confederacy not quite in half and demonstrate to Southerners just how dependent they were on the North for their economic well-being and survival.

A crucial geographical fact that affected the conduct of Civil War campaigns was that while rivers in the Eastern theater all ran horizontally (from west to east), and acted as defensive positions for Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s army, rivers in the West ran mostly north to south and therefore acted as highways for the invaders. And any Union campaign on those rivers necessarily involved both the Navy and the Army in what today we would call joint operations.

What made joint operations so difficult in the 19th century was that there was no existing protocol for Army-Navy cooperation: no Department of Defense or Joint Chiefs of Staff. The ability of Army and Navy commanders to work together depended entirely on their willingness to cooperate. If the commanders embraced partnership—as they did in the successful Union campaign against Vicksburg—joint operations could be effective. If jealousy and rivalry dominated the relationship—as they did during the failed Union effort to capture Charleston, South Carolina—it could poison the campaign.

Technological change also affected joint operations. From the start, the North’s industrial superiority allowed it to produce warships specially designed to function on the Western rivers. They were both steam-powered and armored, though despite that they could maneuver even in relatively shallow water. Union Army General William Tecumseh Sherman said admiringly of them that they could navigate in a heavy dew.

Southerners were equally inventive, but their agricultural economy could not match the Union’s productivity. To defend the rivers, therefore, the Confederacy relied mainly on shore fortifications. As a result, the first confrontations in the Western theater pitted Union ships against Rebel forts.

For a thousand years and more, this was considered an unequal contest. Forts, after all, could not sink. They usually had bigger guns firing from a more stable platform, and it was generally held that any captain of a wooden sailing ship who tried to fight it out with a stone fort was a fool. The technological revolution changed that. Ships were now armored, they had bigger guns that could fire explosive shells, and with steam, they became moving targets.

The first trial of ships vs. forts came at Port Royal, South Carolina, in November 1861. There, a flotilla of wooden Union warships under Flag Officer Samuel Francis Du Pont easily battered the Confederate forts into submission. Five months later, at Fort Henry on the Tennessee River, four Union ironclad warships under Flag Officer Andrew Hull Foote battered that fort into surrender rather quickly, and a thousand miles to the south (as the river winds), Flag Officer David Glasgow Farragut simply ran his wooden ships past the Confederate forts below New Orleans and captured the South’s largest, and arguably its most important, city. But there were limits to what gunboats could do. Farragut could—and did—steam upriver past Baton Rouge all the way to Vicksburg, but he could not capture that Rebel citadel without an army.

Vicksburg is one of the great campaigns of the Civil War, often paired with Gettysburg as the turning point of the conflict, and the key to eventual Union success there was the ability of the Union Army and Navy to cooperate. Indeed, the triumvirate of Sherman, Major General Ulysses S. Grant, and Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter was almost a model of effective joint command. The partnership worked largely because the two generals, Grant and Sherman, went out of their way to be accommodating and deferential to Admiral Porter. As a result, when Grant asked Porter to run a portion of his squadron past the Vicksburg batteries—a dangerous undertaking—Porter agreed to do it.

That was the key to Union success. After Porter made that run, his ships transported Grant’s soldiers across the river below Vicksburg, and that allowed them to approach the city from the east where it was most vulnerable. After several battles and a 47-day siege, Vicksburg fell on the Fourth of July 1863, the same day that Lee began his retreat from Gettysburg in faraway Pennsylvania. Grant could not have done it without the Navy, nor could Porter have done it without the Army. It was a case of the whole being greater than the sum of the parts.

These and other operations demonstrate the profound impact naval forces played in determining the course of America’s greatest war.

Further reading on Civil War navies:

Michael Bennet, Union Jacks: Yankee Sailors in the Civil War (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2004).

Robert Browning, From Cape Charles to Cape Fear: The North Atlantic Blockading Squadron during the Civil War (Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 1993).

__________, Success Is All that Was Expected: The South Atlantic Blockading Squadron during the Civil War (Dulles, VA: Brassey’s, 2004).

Ari Hoogenboom, Gustavus Vasa Fox of the Union Navy: A Biography (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008).

Raimondo Luraghi, A History of the Confederate Navy (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1996).

James M. McPherson, War on the Waters: The Union and Confederate Navies, 1861–1865 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012).

Ivan Musicant, Divided Waters: The Naval History of the Civil War (New York: Harper/Collins, 1995).

William H. Roberts, Now for the Contest: Coastal and Oceanic Naval Operations in the Civil War (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004).

Craig L. Symonds, The Civil War at Sea (Santa Barbara: Praeger 2009; New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).

________, Lincoln and his Admirals (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

Stephen R. Taaffe, Commanding Lincoln’s Navy: Union Naval Leadership during the Civil War (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2009).

Spencer C. Tucker, Blue & Gold Navies: The Civil War Afloat (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2013).

Kevin Weddle, Lincoln’s Tragic Admiral: The Life of Samuel Francis Du Pont (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2005).

Stephen R. Wise, Lifeline of the Confederacy: Blockade Running in the Civil War (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1988).