Junior officers are overburdened with administrative duties that take precedence over learning to be proficient mariners and tacticians. Unfortunately, officers at all levels of shipboard organization are expected to split their time between managing personnel, supervising maintenance, and sundry other tasks, leaving little time for developing shiphandling skills or tactical acumen.

Fortunately, the surface navy can realize significant gains in warfighting readiness at little cost to existing personnel policies by modifying shipboard organization, making slight changes to billeting, and refocusing junior officers, limited duty officers, warrant officers, and chief petty officers. The Arleigh Burke–class destroyer will be used as an example of how this could be implemented.

The destroyer’s shipboard organization at present includes 5 department heads, 25 or so division officers, a handful of limited duty or warrant officers, 30 chief petty officers, and more than 200 enlisted sailors. Unlike in the days of sail, first- and second-tour division officers are no longer responsible only for learning seamanship, standing watch, and becoming capable mariners and tacticians—they are now responsible for personnel, maintenance, and administrative programs. As middle management, they report to department heads who themselves are concerned primarily with the same.

Placing so many administrative responsibilities on junior officers reduces the time available to become master mariners and tacticians. While many factors likely contributed to the 2017 collisions, the lack of knowledge of the junior officers on board—even “the best” on board, as the officer of the deck on board the USS Fitzgerald (DDG-62) was described by one of her former supervisors—indicates a larger problem.1 In the aftermath of the collisions, the Navy administered community-wide navigation tests to its junior officers, and the results were less than stellar.2 To rectify this problem, the surface warfare community should change its shipboard organization and realign junior officer priorities to take advantage of existing personnel and expertise billeted to destroyers.

A New Organization

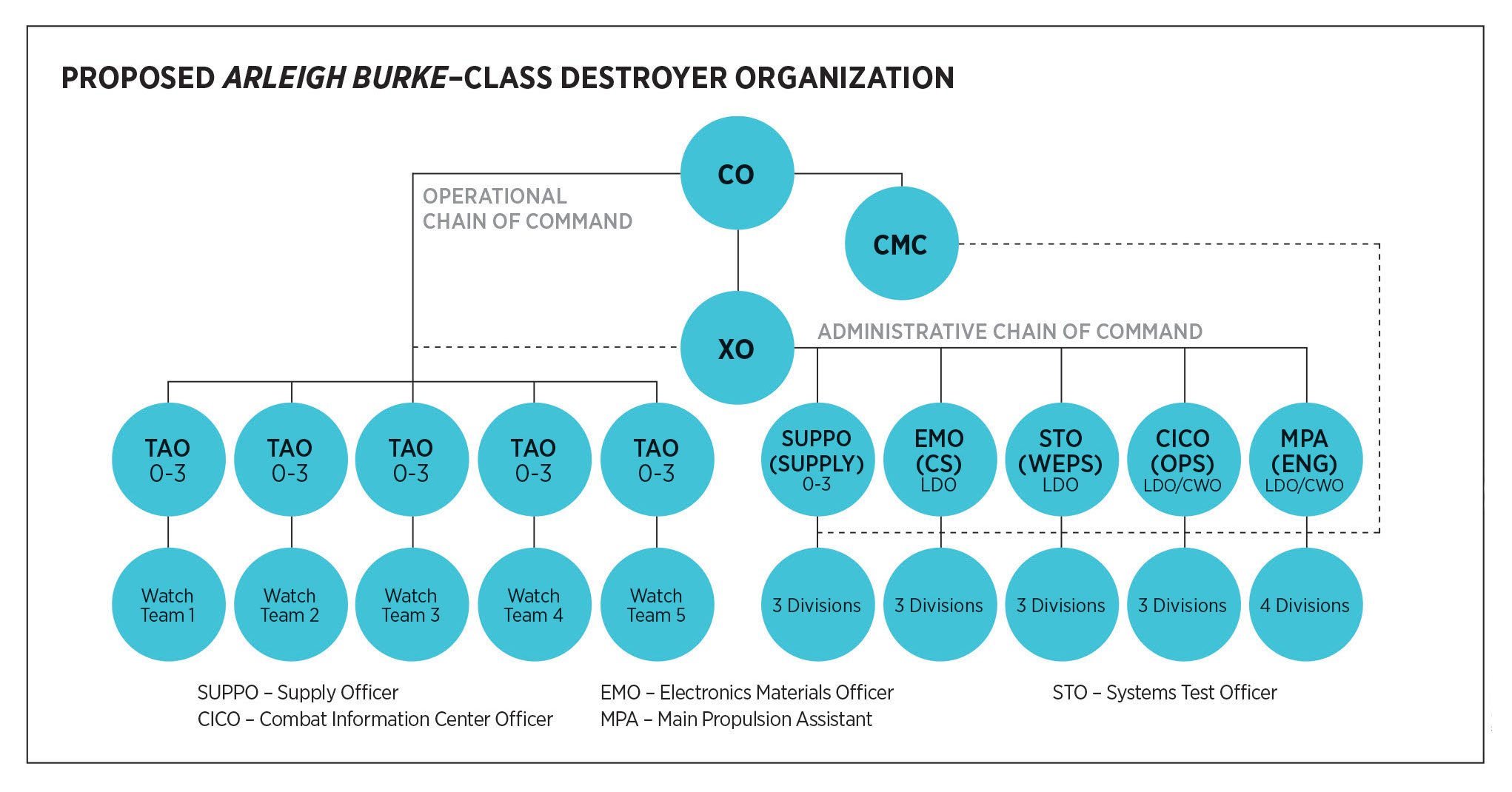

In my proposal, the top ship leadership positions remain unchanged. The commanding officer (CO) remains responsible for all aspects of the command for the warship. Similarly, the role of the executive officer (XO) remains unchanged. The XO reports to the CO for all matters of maintenance, personnel, and general administration of the ship, as is done currently. This also remains the case for the command master chief (CMC).

At the department-head level, significant improvements in watchstander proficiency and warfighting readiness can be achieved. The title of department head becomes something of a misnomer. Below the XO, shipboard organization would be split into two parallel chains of command, one for maintenance and administration and the other for operations. No longer will lieutenants and lieutenant commanders assigned to a destroyer be responsible for departments as they currently are structured.

Instead, the ship’s five line-officer department heads will be billeted as tactical action officers (TAOs), responsible for watchstanding and leading the training and mentorship of junior officers and sailors who compose their watch teams (see chart, below). In addition, the most senior of these officers will have a collateral duty as the senior watch officer and will be responsible for watch team organization. Another of these officers will be the ship’s navigator. A Supply Corps staff officer and an assistant supply officer will continue to lead the supply department, with duties unchanged.

From Middle Managers to Mariners and Tacticians

The primary division officer role will also shift to watchstanding. Second-tour division officers will be billeted to destroyers as combat watchstanders, serving as TAOs in training. Following warfare tactics instructor (WTI) training, six of these officers will be assigned to a destroyer as air warfare officers (two), antisubmarine warfare officers (two), and antisurface warfare officers (two). Each will stand antiair warfare coordinator, antisubmarine warfare coordinator, and antisurface warfare coordinator watches, training one another under the guidance of the TAO at his or her respective warfare area and watch station. The objective is that each will become qualified in all three warfare areas to provide sufficient watch team depth. Qualification as TAO will follow as the capstone accomplishment of their tour.

Special evolutions, such as underway replenishment and pulling into and out of port, will provide opportunities for second-tour division officers to keep their shiphandling skills sharp, as they do now. However, combat watchstanding will take priority. In addition to their primary watchstanding duties, these officers will qualify to fill specialized underway roles such as antiterrorism tactical watch officer; underway replenishment safety officer; visit, board, search, and seizure officer; and strike officer.

First-tour division officers will be assigned to destroyers as bridge and combat watchstanders and will stand the same bridge watches as they currently do: conning officer, junior officer of the deck, and officer of the deck. In the combat information center (CIC), however, they will stand watches under the instruction of qualified second-tour division officers, during which time they will gain the knowledge necessary to succeed during their second tours. Particularly talented first-tour officers could even qualify early, thereby accelerating their careers and adding depth to the watchstanding bench.

While junior officers would gain less experience managing sailors and programs during their first and second tours, the loss is worth the benefit of more tactical and mariner proficiency. And they would still gain some leadership experience leading and training their watch teams. In fact, this reorganization would likely improve the quality of evaluations, requiring emphasis on tactical proficiency for officers and sailors alike.

Warrant officers and limited duty officers (LDOs) will be the senior officers of the shipboard maintenance and administrative chain of command. Their roles will be similar to the department heads under the existing shipboard organization, reporting directly to the XO for all equipment and personnel under their charge. These officers will focus exclusively on maintenance, technical training, and operating assigned equipment and will not be underway watchstanders. A destroyer will continue to require four warrant officers or LDOs, serving as systems test officer, electronic materials officer, CIC officer, and main propulsion assistant (see chart). By limiting warrant officer and LDO responsibilities to maintenance and personnel management, their technical and leadership experience will be fully realized.

An Opportunity for Chiefs

In the enlisted ranks, the organizational structure remains largely unchanged; sailors are already billeted to focus primarily on either the maintenance or operation of equipment, with some necessary overlap. These sailors will continue to report directly to chief petty officers, who will in turn report to the warrant officer or LDO leading their department. Chief petty officers will handle all aspects of maintenance, training, and personnel management for their assigned divisions. Petty officers and junior sailors will continue to maintain equipment and stand watch. With these recommended changes to department head, division officer, and senior enlisted sailor responsibilities, the majority of watch stations in the CIC will remain manned as they are currently, with the only major changes being that warfare coordinators are exclusively junior officers, freeing up additional senior enlisted watchstanders for other roles.

For chief petty officers, this reorganization would rightfully return them to their place as technical experts and leaders of sailors. The rank of chief petty officer was established in 1893, not only to bridge the gap between enlisted personnel and officers, but also to give greater authority to technical experts in the fleet, as they provide deckplate leadership to the sailors under their charge. Today, more than ever, the surface navy needs technical expertise to manage the very complex systems of a modern warship. Chiefs are fond of noting that the Navy confers greater responsibility and authority on them than other services do at the E-7 to E-9 paygrades. By making chiefs solely responsible for their personnel and equipment, not jointly with a division officer, this proposal reinforces the notion that the buck stops with the chief.3

A shipboard organization similar to that proposed in this article was ostensibly tested on the USS Decatur (DDG-73) in 2004. However, it is difficult to find detailed information on what took place. Retired Master Chief Paul Kingsbury wrote on this experiment and other past attempts at empowering the senior enlisted ranks in Proceedings last year, noting that they “succumbed to poor strategic communication, implementation, and cultural pushback from CPOs and officers.”4

Time for a Change

This proposed reorganization will likely appear radical to current and former sailors. But the modifications are proposed bearing in mind they would likely take a great deal of time to implement and would have to be done carefully to ensure neither knowledge nor personnel gaps occur. The Navy has consistently invested in advanced weaponry and combat systems equipment, but despite continual calls for improvement, the surface navy has not properly invested in adequate training for its future leaders. Better equipment and new concepts are needed, but without capable and competent officers to operate and employ them, the nation’s investment will not have the desired result.

Fortunately, increasing the investment in junior officers does not have to be expensive and can largely be built off the existing training structure to take advantage of efforts the Navy has already expended. Within ten years, the surface navy will have new ships and new combat system capabilities that will ensure it maintains a high-end combat edge over potential adversaries. If the Navy invests now in better training and in a smarter shipboard organization that allows junior officers to maximize their warfighting skills, it will reap the benefit of having a highly trained, tactically proficient surface warfare community ready to sail the future fleet into battle.

1. T. Christian Miller, Megan Rose, and Robert Faturechi, “Death and Valor on a Warship Doomed by Its Own Navy,” ProPublica, 6 February 2019.

2. David B. Larter, “Troubling U.S. Navy Review Finds Widespread Shortfalls in Basic Seamanship,” DefenseNews, 6 June 2018.

3. Don A. Kelso, “The Role of the Chief Petty Officer in the Modern Navy,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 83, no. 4 (April 1957).

4. Master Chief Paul Kingsbury, USN (Ret.), “Make Better Use of the ‘Super Chiefs’,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 145, no. 5 (May 2019).