From a resource point of view, the U.S. Navy has not been doing well lately. Its program to expand the fleet to 355 ships, and the shipbuilding budget to support it, has suffered a series of setbacks—whether being raided for money to build a border wall, to fund the replacement ballistic-missile submarine program, or to bolster current readiness. Congress, despite its desire for a bigger fleet, has not increased the Navy’s top line sufficiently to accelerate ship construction, and, perhaps worse, the Navy has been unable to produce a force structure assessment (FSA) that passes muster with the Secretary of Defense.1

The heart of the problem, though, is the combination of constrained budgets and the rising cost of any kind of combatant. The Navy has attempted to deal with the problem in three different ways: calling for a larger budget share; focusing on capabilities, not numbers; and trying to count unmanned vessels as battle force ships. None of these seems to satisfy a Congress that has grown increasingly skeptical of the Navy’s force procurement process, problems with the Gerald R. Ford-class carrier and littoral combat ship programs feeding that skepticism.

To conduct a coherent FSA under current conditions, the Navy needs a different way of calculating its combat power. The principal method of counting naval strength should be by the number of missile shooters—including units from all the services.

The Strategic Dilemma

After World War II, the Navy enjoyed virtually absolute command of the world’s oceans. As the Cold War developed, this allowed the service to encircle Eurasia with naval force to prevent the Soviet Union from expanding its buffers beyond Eastern Europe.2 Strategic dispersal was necessary to execute this strategy—both to have force available at threatened points (Korea, Vietnam, etc.) and to engage with and reassure allies and neutrals—and it was possible both because the Navy maintained a sufficiently large inventory of ships and because the potential locus of the naval component of war with the Soviet Union roughly corresponded to peacetime deployments for presence.

The Navy’s success during this period—from the Battle of Midway through the collapse of the Soviet Union—was based primarily on the concentration of naval power in the aircraft carrier. This geopolitical achievement generated institutional momentum for carriers inside the Navy and Congress, which eventually passed legislation requiring the Navy to maintain at least 11 carriers.3

But success often contains the seeds of its own destruction. Throughout the post–Cold War era, the Navy’s inventory of battle force ships went from almost 600 ships at its zenith to fewer than 300. Its mission requirements in terms of presence, however, remained constant or, after the 9/11 attacks, actually increased. Since presence tended to be defined in terms of carrier battle groups, the pressure on Navy force structure grew.

Today, the rise of a competitive and potentially hostile China and a resurgent Russia have created a new strategic dilemma for the Navy: The locus of potential war-fighting does not correspond to the Navy’s peacetime presence distribution. Moreover, it is not clear that the aircraft carrier is any longer the strategic all-purpose vessel.4

On the one hand, the Navy needs to maintain or even expand its global presence operations—to maintain maritime security, keep key chokepoints open, and deter regional threats such as Iran, among other reasons—which demands strategic dispersal. On the other hand, deterring China from invading Taiwan, closing off the South China Sea, and intimidating regional democracies requires strategic concentration of force. In the Cold War era, the Navy had sufficient force inventory to square the circle through a surge strategy, keeping significant forces available in home waters for deployment to where trouble erupted. Today’s pared-down fleet has far less ability to generate surge forces.

A different approach is needed.

The Missile Age

Antiship missiles have been deployed at sea since the 1960s, and their potential to revolutionize naval warfare has been widely recognized and acted on, especially by nations unable to build and deploy aircraft carriers. The U.S. Navy, for its part, has until recently all but ignored the potential of the antiship missile—partly for lack of an effective over-the-horizon target localization and identification system—but the sheer magnitude of Chinese anti-ship missile production has forced a reevaluation.

Distributed maritime operations envisions the installation of long-range antiship missiles on cruisers, destroyers, littoral combat ships, and submarines.5 While this takes some of the offensive pressure off aircraft carriers and is a step in the right direction, its detailed provisions, many of which are classified, may not constitute a full commitment to missile-centric combat at sea. In any case, the true impact of the antiship missile has not been incorporated into fleet counting rules, which still privilege aircraft carriers and ships able to escort them.

Throughout naval history there has been a close relationship between the dominant weapon and the ship on which it is installed. In the age of fighting sail, for example, the smooth-bore cannon drove the construction of large three-deckers able to mount a massive broadside; in the age of dreadnoughts, huge ships with extensive armor were needed to take advantage of the large-caliber naval rifle; in the age of aircraft carriers, progressively larger hulls were needed to support ever heavier and larger aircraft. But the antiship missile breaks that relationship. Most any kind of vessel can carry a few if not many missiles. Moreover, a vessel’s speed, armor, and other systems are almost irrelevant, and, as the Chinese have discovered, long-range antiship missiles do not even require ships; they can be land-based.

While the advent of the highly capable antiship missile has exacerbated the U.S. Navy’s strategic dilemma, its breaking of the relationship between weapon and ship characteristics offers a way out.

Shooters

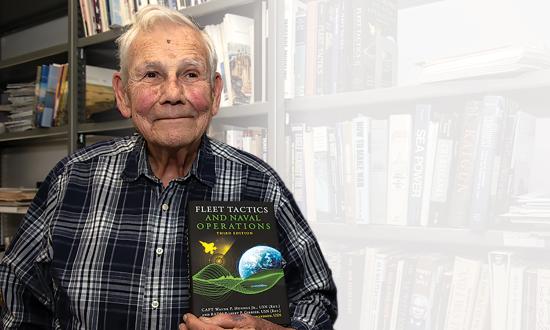

In Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations, the late Wayne Hughes lays out salvo equations that describe the potential dynamics of missile combat and concludes that for combat inside the threat rings of land-based missile systems, a fleet should be composed of numerous small missile craft.6 The numbers indicate that large, highly capable ships such as Aegis cruisers eventually will fall prey to repeated missile attacks.

A true commitment to distributed operations likely requires new classes of vessels and new ways of “feeding the fight.”7 The number of missiles fired, both offensively and defensively, matters. It is critical to get missiles into shooting positions as economically as possible, to maximize their number. If money is to be spent, it should be for scouting, identification, and command and control.

The Hughes equations have significant implications for fleet size calculation. While the number of missiles matters, so does the number of shooting platforms. Therefore, the true strength of the fleet in relation to the Chinese littoral defense (and offense) establishment is a function of the number of missile shooters the United States can bring to bear. Any number of combinations of various kinds of vessels could be conceived, but the bottom line is total number.

The size of each vessel is relevant in terms of seakeeping and logistical requirements, but in the current budget environment, cost is a primary consideration. One proposal is to procure used merchant ships and convert them to missile shooters, commissioned and manned by Navy crews, but the current bias toward aircraft carriers and the ships to escort them may be a roadblock to even a pilot project.8 Small combatants such as a new frigate or corvette also might be part of the solution, although costs could prevent procurement of adequate numbers, and smaller craft carry significant logistics requirements. The installation of missiles on amphibious and even service force ships offers another way of increasing the number of shooters.

Another option would be to include Air Force big-wing bombers such as the B-1B, each of which can carry a number of antiship missiles. A series of wargames conducted at the Naval War College in the early 2000s indicated the potential value of these aircraft in a naval war.9 The nascent Marine Corps and Army concepts for small detachments operating coastal antiship missile launchers also are a potential source of missiles. This heterogeneous array of shooters greatly complicates the defensive requirements for China. Tying this all together is a new initiative for joint command and control.10

It is reasonable to think Congress might oppose adopting a new measure of combat power, being steeped for so long in estimating naval strength by numbers of hulls and given the influence shipbuilding wields. Recent pushback on Navy proposals to reduce hull numbers and introduce unmanned platforms suggests that any proposal to change the way the service counts combat power would be met with skepticism.11 However, counting shooters has the advantage of having a direct relationship with actual warfighting, and if it demonstrated to Congress a clear link between fleet structure and combat capability, that skepticism likely could be overcome.

Case for a Bifurcated Fleet Design

The number of battle force ships does have some meaning for conducting continuous global presence, but it conflates war-fighting with constabulary operations, things the prophet of U.S. seapower, Alfred Thayer Mahan, regarded as separate functions. From Korea to Operation Iraqi Freedom, power projection operations conducted in benign sea control environments—usually by individual carrier strike groups—have been touted as warfighting. Due in part to this conflation, the institutional momentum of the aircraft carrier has remained unchallenged. When the carrier strike group is regarded as the unit of issue for both presence and warfighting, fleet design and architecture are handcuffed.

The issue is not the carriers’ vulnerability. Modern nuclear-powered aircraft carriers are robust vessels that are likely to be able to absorb damage and keep operating, and in any case are well defended by their escorts and air wing. The real problem is their waning utility in warfighting and their expense, numbers, and availability. Each carrier is a critical strategic asset and must be subjected to risk only if the potential strategic payoff for a particular engagement or battle warrants. That complicates decision-making for the U.S. command-and-control structure up through the White House, as it makes it hard to balance risk and reward.12

In an extended combat scenario in East Asia, logistics is a potential problem. In terms of missiles, the Navy’s inventory is governed by vertical launching system (VLS) cells. As the battle proceeds, ships will expend their magazines. VLS is difficult to reload at sea, so ships likely will have to retreat to a port. The fleet commander will have to establish doctrine on when to retire, but it is likely that ships will have to do so with missiles still in their cells so they are not defenseless. Thus the number of available missiles for shooting would be less than the number of cells. This conundrum would be complicated if the missiles were multimission, for example, the SM-6.

Calculating combat power by counting hulls does not properly reflect logistic matters such as this. Counting shooters of all types would provide a better basis for operational planners to provide for an extended fight and would offer a more relevant connection between procurement and operational planning. In the context of counting all shooters, how many ships and subs does the Navy really need in a full combat scenario, and by derivation, how many total of each kind in a full global fleet design?

Fleet design should be bifurcated into constabulary work and warfighting. The Navy must do both, but attempting to do so based on a single index for assessing capability, especially in a constrained budget environment, is a recipe for “spectacular failure.”13

For warfighting, the number of missile shooters should be the principal measure and should include assets from all the services. There is a “correct” number given the Chinese order of battle and the likely missions U.S. forces would be assigned. For example, it might be strategically sufficient to disrupt a Chinese attempt to invade Taiwan rather than try to achieve sea control in the region. That would affect the number and types of shooters needed. In any case, basing naval combat strength on the number of shooters would liberate fleet design and could have beneficial effects on deterrence since China could more easily see how U.S. strength could be applied.

Presence still would be dependent on ship numbers, but freed from fusion with warfighting needs, the types of ships constituting the force could be reimagined. Everything from Coast Guard–style cutters to big-deck amphibious ships could fit the mix. And a redesigned presence fleet would allow the nation’s aircraft carriers to become the surge force. This would permit a more rational calculation of how many are needed and relieve the pressure on them for continuous deployment.

Delinking presence and warfighting force design also could free money for research and development—and more fleet experimentation. An insidious side effect of the institutional momentum favoring aircraft carriers and the related battle force ship counting convention has been the ossification of the Navy’s ability to flex and adapt. A series of fleet battle experiments in the late 1990s and early 2000s, along with the establishment of the Navy Warfare Development Command, failed to achieve the innovation everyone sought, and the process kind of petered out.14 The Navy is now trying to organize a Large Scale Exercise to reanimate innovation in fleet design. Without a rethinking of the Navy’s strength-counting process, the prospects for it producing needed change and a way out of the strategic dilemma are dim.

1. Ben Werner, “SECDEF Esper Blames Failures of Optimized Fleet Response Plan for Delay in 355 Ship Fleet Outlook,” USNI News, 26 February 2020, and Mark Cancian and Adam Saxton, “The Spectacular & Public Collapse of Navy Force Planning,” Breaking Defense, 28 January 2020.

2. Samuel P. Huntington, “National Policy and the Transoceanic Navy,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 80, no. 5 (May 1954): 483–93.

3. 10 U.S. Code, section 8062, U.S. Navy Functions, Composition, para (b), which states: “The naval combat forces of the Navy shall include not less than 11 operational aircraft carriers.”

4. CAPT Robert C. Rubel, USN (Ret.), “Use Carriers Differently in a High End Fight,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 144, no. 9 (September 2018): 34–39, and “The Future of Aircraft Carriers,” Naval War College Review (Autumn 2011): 13–27.

5. The most recent Chief of Naval Operations public guidance, FRAGO 1/2019 A Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority, makes reference to the concept. For a basic definition of distributed maritime operations, see Navy News Service, “CNO Visits Navy Warfare Development Command,” NNS170413-14, 13 April 2017.

6. CAPT Wayne P. Hughes Jr. and RADM Robert P. Girrier, USN (Ret.), Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations, 3rd ed. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2018), 284, but see also chapter 13, “Modern Tactics and Operations.”

7. See CAPT Robert C. Rubel, USN (Ret.), “Cede No Water: Strategy, Littorals and Flotillas,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 139, no. 9 (September 2013): 40–45, and “Think Outside the Hull,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 143, no. 6 (June 2017): 42–47. The impact of the Zumwalt class is unknown, but there are only three, and absent the railgun and laser-based defenses, it likely would be only marginally more useful than current classes.

8. CAPT R. Robinson Harris, USN (Ret.), et al., “Converting Merchant Ships to Missile Ships for the Win,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 145, no. 1 (January 2019).

9. The Halsey Group is an advanced research elective for about 25 Naval War College students who conduct iterative wargaming at a highly classified level. The group includes officers from all services.

10. Theresa Hitchens, “New Warfighting Plan Will Define ‘Top Priority’ JADC2: Hyten,” Breaking Defense, 29 January 2020.

11. David B. Larter, “Congress Slows the Navy’s Roll Toward a Robot-Ship Future,” Defense News, 10 December 2019, and Joseph Trevithick, “Congress Pushes Back on Stunning Navy Plan to Cut Back on Cruisers, Destroyers, Subs and More,” The War Zone, 26 December 2019.

12. CAPT Robert C. Rubel, USN (Ret.), “The Future of Aircraft Carriers: Consider the Air Wing, Not the Platform,” Center for Maritime and International Security, 3 December 2019.

13. Cancian and Saxton, “The Spectacular & Public Collapse of Navy Force Planning.”

14. For a critique of the Fleet Battle Experiment program, see Shelly Gallup, Gordon Schacter, and Jack Jensen, Fleet Battle Experiment Juliet Final Reconstruction and Analysis Report (Monterey, CA: Naval Postgraduate School, April 2003), 61-67.