I was one of Captain Wayne Hughes’ first operations research thesis students in 1989–90. Since that time, I have thought a lot about the application of his theory to the development and practice of naval tactics, and I have concluded that a deep understanding of his book Fleet Tactics is invaluable to naval officers.

What does it mean to “attack effectively first”? Why is doctrine “the glue of tactics”? What is the goal of “antiscouting”? Why do “men matter most”? If you don’t know the answers to these questions, you haven’t read one of the three editions of Fleet Tactics. If you are a seagoing line naval officer who has not, you have deprived yourself of an important resource.

Which Edition?

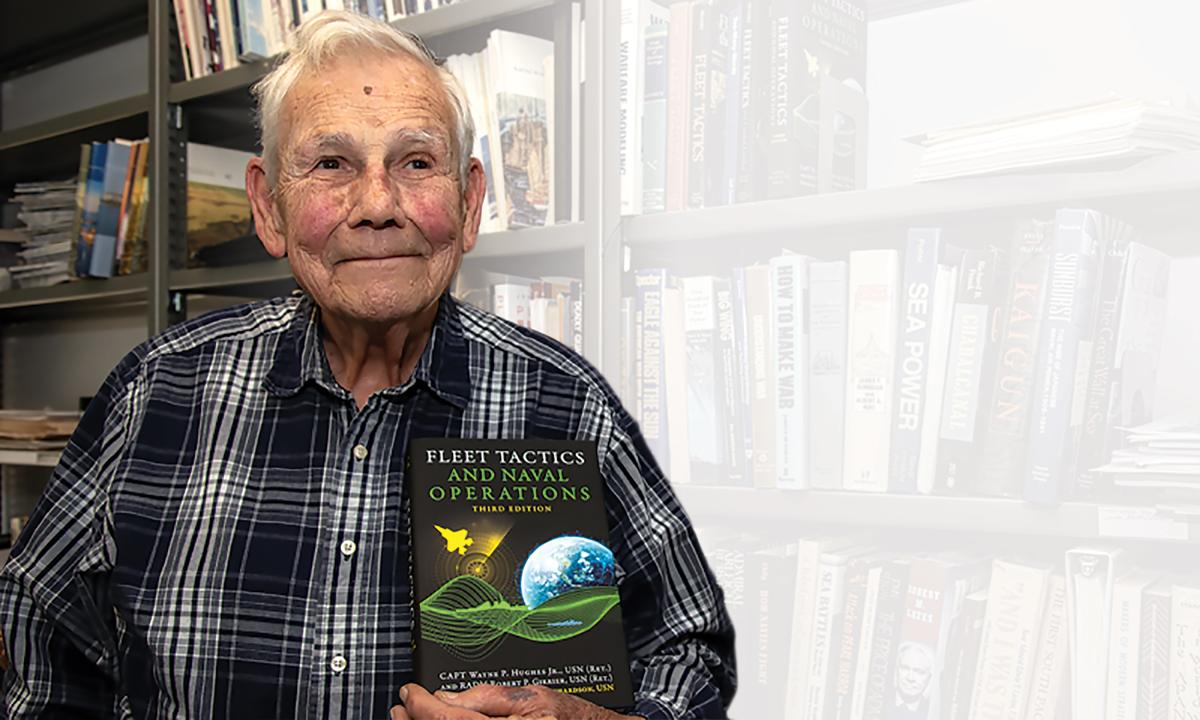

Of the three editions of Hughes’ book, his first, Fleet Tactics: Theory and Practice (Naval Institute Press, 1986), is the simplest and most elegant. It embodies Hughes’ original thinking on naval tactics without his subsequent efforts to tailor his theory to the contemporary focus of U.S. Navy planners. I recommend reading this edition first, to understand Hughes’ original ideas and get a feel for how he developed them throughout his naval career.

The second edition, Fleet Tactics and Coastal Combat (Naval Institute Press, 1999), was published when littoral warfare doctrine and force structure were under development, and the third, Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations (Naval Institute Press, 2018), was published when cyber warfare and cybersecurity were the focus of the planners. While both of these volumes incorporate Hughes’ tactical theory, it is more difficult to discern the theory from the context of the issue of the day.

The Importance of History

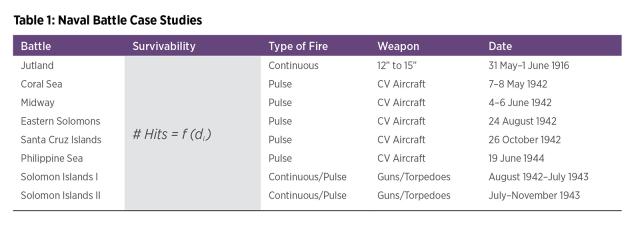

Hughes’ ideas flow from his detailed study of naval history, and he uses historical case studies to illustrate his tactical theory (see Table 1). He focuses primarily on naval battles in the two world wars because the warships, weapons, and sensors employed are most similar to those of the present day. In these case studies, Hughes searched for commonalities that could provide the basis for his theory. He expressed these commonalities as the cornerstones, constants, and trends of naval battle.

Hughes’ case study analysis focused on ship survivability, weight of ordnance placed on target, and scouting effectiveness. Drawing on the work of his students and colleagues, he reasoned that the number of hits required to take a warship out of action was a function of ship displacement. His conclusions concerning scouting effectiveness derived from his analysis of the night surface battles in the Solomon Islands, in which the side that found its enemy first usually won. Regarding ordnance, Hughes implicitly categorizes each battle by “Type of Fire,” including:1

• Continuous: Ships’ guns during the first half of the 20th century fired so rapidly that they can be modeled like a continuous function on a graph. A battle such as Jutland, in which the combatants use rapid-fire, large-caliber guns exclusively, is a continuous-fire battle.

• Pulse: Bombs and torpedoes are fired in pulses, which can be modeled like discrete functions on a graph. A battle such as Midway, in which the combatants use aircraft ordnance (bombs and torpedoes), launched in large “pulses” from individual and discrete aircraft squadrons, is a pulse-fire battle.

• Continuous/Pulse: This is when both types of fire are used in the same battle, such as in the Solomon Islands surface engagements, where both the United States and Japan used continuous-fire gunnery and Japan also employed salvoes (pulses) of torpedoes.

Cornerstones, Trends, and Constants

Hughes determined several characteristics of naval battle, which serve as the building blocks of his tactical theory.

The five cornerstones are immutable concepts applicable to naval warfare:2

• Men matter most. Training, morale, physical and mental health, care and feeding—no battle can be won without a team that is highly trained and motivated.

• Doctrine is the glue of tactics. Doctrine is the commander’s operational battle plan—his standing operations order—that enables and enhances tactical choice in battle.

• To know tactics, know technology. Technology advances keep weapons in a state of change. Tactics must reflect the capabilities of contemporary weapons.

• The seat of purpose is on the land. Fleet engagements are not fought in a vacuum but always are connected to and ultimately support operations on land.

• Attack effectively first. The outcome can be not just victory but overwhelming victory for the force that attacks effectively first.

These cornerstones are foundational and are characteristic of every naval battle regardless of the era or type of warship. The tactician must take them into consideration, asking questions such as, What is the state of morale and training in my force and that of my enemy? What doctrine is most applicable to my planning? What advantages/disadvantages does my technology give to my force, and what does my enemy’s give to him? How well does the battle for which I am planning integrate into higher authority’s operational planning? Does my plan give my force the ability to attack effectively first?

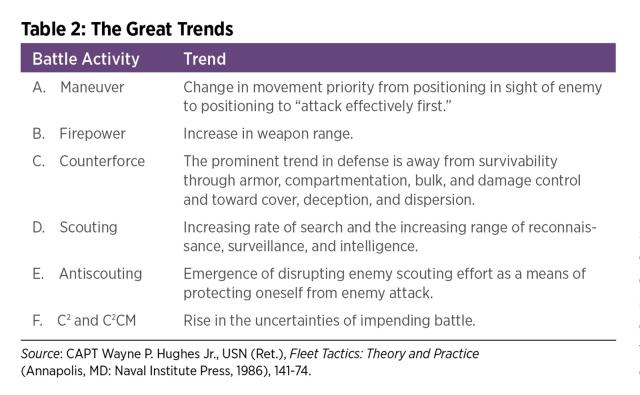

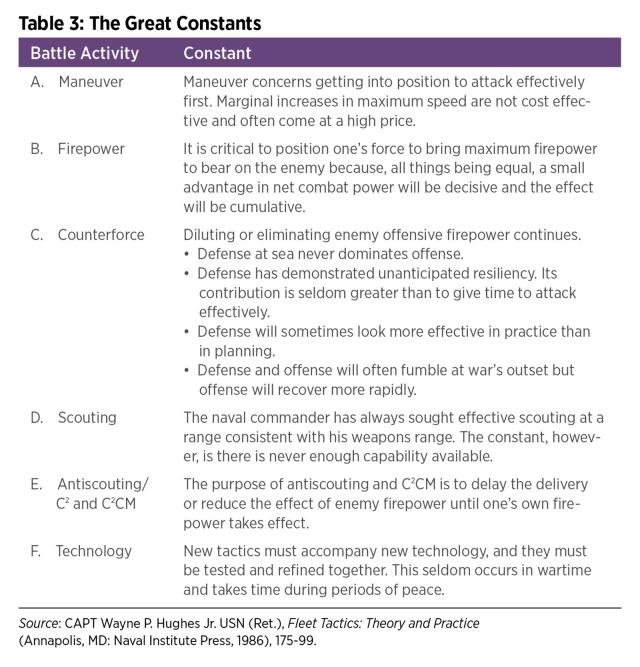

Unlike the cornerstones, which inspire the tactician to ask and answer specific questions during the tactical planning process, the great trends and great constants are more like ideas with which to be familiar during that process and in battle. (See Tables 2 and 3.) For example, the constant that “there is never enough [scouting] capability available” is a reminder to position one’s scouting forces wisely to guarantee the highest probability of detecting the enemy. Likewise, the trend of “increasing rate of search and the increasing range of reconnaissance, surveillance, and intelligence” that characterizes scouting reminds the tactician that these improving capabilities offset to some degree the constant of shortages in scouting assets.

Mathematical Modeling

As a professor of operations research at the Naval Postgraduate School, Hughes naturally chose to express his theory in mathematical terms: his salvo equations. The equations descend from the classic force-on-force attrition model developed by Frederick W. Lanchester in 1916, which can be expressed by the following example:3

Suppose that, in a land battle, two squads of soldiers fight each other. Each soldier on each side is trained as well as every other soldier so that the probability that any one soldier will kill the enemy soldier he is aiming at is 0.30. Suppose that one of the squads contains ten members and one contains only eight members.

Because the ten-man squad has two additional men, those men can concentrate their fire on men already being fired upon. The likelihood those targets will be killed is higher than 0.30. If killed, there are fewer men on the smaller side to engage the larger enemy. The larger side continues to gain an advantage and wipes out the smaller side with loss of only a few men.

The mathematics in Fleet Tactics is a suggestion that naval combat is a force-on-force process similar to that modeled by Lanchester. Hughes plants this seed but leaves it to the reader to decide whether to use one of the many versions of the salvo equations in his other writings or the work of his thesis students, almost all of whom incorporated them in some form. There is virtually no other mathematics in any of the three editions of Fleet Tactics. Hughes uses a number of numerical relationships to illustrate the outcome of the battle case studies, but he leaves it to the reader to decide whether to apply his theory mathematically or in any other way with which the author feels comfortable. Mathematics, after all, is just a language.

I suspect Hughes left out the mathematics so that those prone to “math anxiety” would not be distracted from understanding his theory.

Start Reading

Wayne Hughes’ passing in December 2019 deprives the naval community of further editions of his seminal work. Yet, he has left an important legacy of naval tactical theory. His writings will guide you to being a better tactician and, therefore, a better naval officer. You have only to open the book and start reading.

1. CAPT Wayne P. Hughes Jr., USN (Ret.), Fleet Tactics: Theory and Practice (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1986), 63–65.

2. Hughes, Fleet Tactics, 16–39.

3. F. W. Lanchester, Aircraft in Warfare, the Dawn of the Fourth Arm (London, Constable and Co., 1916), 41–53.