Commander Nelson recently spoke with retired Navy Captain Peter Swartz about his career as a naval strategist. Peter retired from the Navy in 1993 and from full-time work supporting the Navy at the Center for Naval Analyses (CNA) in January 2019. His naval and analytical career has spanned more than five decades. From the rivers of Vietnam to the halls of the Pentagon, he has—and continues—to shape naval strategy.

Nelson: Peter, you’ve had a fascinating naval career. You made it to captain yet never held a warfare designation. How did this happen?

Swartz: My father served as a private first class under General Patton. He drove across France, slept in the mud, and got blasted by a German half-track with an 88-mm cannon. He came home and vowed his son would become an officer, not enlisted, and that I would be in the Navy, where they slept in clean sheets. So, the natural thing was for me to join ROTC when I enrolled at Brown University.

I discovered that half the guys there were on scholarship, but I calculated that working as a union baker in the summers, I could make more money, so I didn’t need the scholarship and the additional two-year commitment that would entail. I was interested in foreign affairs and thought I could serve in the military and then get out and join the foreign service. I got the top grades in my ROTC cohort in academics but was at the bottom of my class in military aptitude.

After graduation, the Navy allowed me to go to graduate school, and I went to the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies for a couple years. Then it was time for me to serve. I certainly didn’t want to go on board a ship, so they said, “Well, you can go to Coronado and teach guys about the political-military issues in Vietnam.” At Coronado, I was on a staff of 15 guys, and all but me had been to Vietnam. The war was raging. I was teaching socio-political subjects. It didn’t make any sense. So I decided to volunteer to go to Vietnam. This involved an extension of my commitment, but I said, “What the hell.”

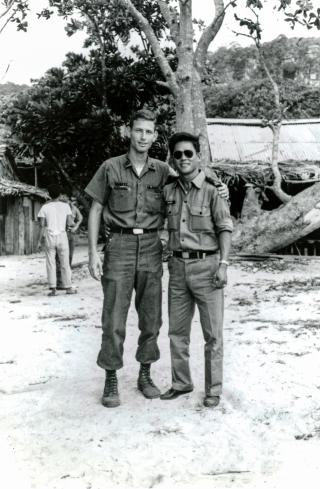

I identified a billet in-country because I knew everybody out there. I wound up as an advisor for the Vietnamese Navy in the Fourth Coastal Zone. I did that for about eight months. I was doing what I wanted to do, learning about the Vietnamese, about war, and about the Navy. Then I got ordered to Saigon to relieve a commander who was leading psychological operations. I didn’t want to go, but I was told, “Hey, lieutenant, it doesn’t work that way. You’ll go where you’re ordered.”

They asked why I didn’t want to be in Saigon. I told them the place was a flesh pot, everyone had girlfriends. I didn’t go to Vietnam for that. I also was not interested in staff work—I wanted to be with the boats; I wanted to be an operator. I was a reservist, there for a couple of years, not designated, and I didn’t need staff duty for my career. As it turned out, I met the woman who would become my wife in Saigon. We’ve been married now for almost 48 years.

No one can repeat the kind of career I have had. It was very strange.

Nelson: Do you speak Vietnamese?

Swartz: Yes, but not as much now as I did back during the war. The average Navy advisor who worked with the Vietnamese got six weeks of language training; I got 12 weeks. So I was twice as fluent as other officers. I also discovered that I was a really good staff officer. It was the first time on my fitness report I got graded 1 out of 12 lieutenants on the staff. I eventually caught the eye of Vice Admiral Elmo Zumwalt and his chief of staff, Captain Emmett Tidd, later Vice Admiral Tidd. I discovered that these career officers weren’t so bad, and I actually liked being around them. They were operationally oriented. I was much better as a staff officer than I was an operator. That was mortifying, but it was the truth.

Nelson: Did you extend your tour in Vietnam?

Swartz: I was ready to get out of the Navy, then Admiral Zumwalt asked me to extend in Vietnam, and I did. When I came back to the States, Zumwalt wanted me to work on the Navy’s intercultural relations program. So I stayed on for a while until it was clear I wasn’t going anywhere.

The Navy then opened a few human resource management jobs, one of which was in London. I had two years before I was up for lieutenant commander, and I knew I was going to be passed over because the career path I followed didn’t promise promotion. So I asked my wife, “How would you like to go to London?” We went, had a daughter, and had a great time. Yet, lo and behold, I got promoted, based on God knows what.

My boss, who was pretty savvy in such matters, said I should write to the Bureau and ask what they had in mind when they promoted me. What potential did the board think I had? So, I wrote a letter. The director of officer personnel sent back the letter saying I had two choices: I could stay with human resource management, or I could be a pol-mil strategic subspecialist. Well, that wasn’t a hard choice. I wanted to be a pol-mil strategic analyst. The Navy said okay, and I took orders to the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations’ Strategy, Plans, and Policy Division (OP-60), which is now OPNAV N50.

They told me I could have a viable career if I did well. The letter was signed by Rear Admiral Carl Trost. I treasured that letter. Every time I was up for a board or award, to explain to people how I got in this subspecialty, I simply sent them a copy of Admiral Trost’s letter.

I did a good job at OP-60 and especially learned a lot from one of the Navy planners, then-Captain James “Ace” Lyons. Then friends and admirals told me to go back to school. They sent me to Columbia University. I worked on a dissertation, and while I didn’t finish, my entire later Navy life was a spin-off of the classes I took and the research I did while I was at Columbia.

I then came back to OP-60—same chair, same desk. My new bosses had me write change of command speeches, among other menial tasks. It was not working. I wanted to get out.

About that time, Captain Roger Barnett relieved my boss. He said Vice Admiral Art Moreau had his eye on me; I was going to write something called the Maritime Strategy. So my boss and I worked on something that two friends of mine—Lieutenant Commander Stan Weeks and Commander Spence Johnston—had started the previous year, and we created the document people know today as the Maritime Strategy.

Then I was ordered to work for John Lehman, someone I really didn’t want to work for. He was this brash Secretary of the Navy, and I thought strategy was something the uniformed officer corps wrote, not civilian appointees. But it turned out to be a terrific tour. I rarely saw the Secretary, but if I went to my immediate boss in the morning with an idea, he would see Lehman at lunch, and by that afternoon I would be given carte blanche to execute my idea. It was an amazing job. I was one officer away from the head decision-maker in the Navy. And the admirals I worked for, like Frank Kelso and Jerry Johnson, were movers.

By now I was up for captain. The president of the selection board was an old boss, Admiral Robert Kirksey. From what I understood at the time, Kirksey did not get along with John Lehman or Vice Admiral Ace Lyons, who was a close associate of the Secretary and the nearest thing I had to a head of my “community.” So I thought I was toast. All I had done for him was write speeches. But they must have been good speeches because I was promoted.

So now I’m at terminal grade, and I’m two ranks higher than I ever thought I would be. I took my friend Admiral Hank Mauz’s advice and got a job in Brussels. My family and I were there when the Berlin Wall came down.

Nelson: How did you end up working for Colin Powell when he was Chairman of the Joint Chiefs?

Swartz: While in Brussels I was the senior naval officer at the U.S. Mission to NATO. I worked well with Admiral Jim Hogg, who was the senior naval officer at the U.S. Military Delegation. Eventually he said, “Peter, I got you a good job in Washington.” He said I was going to be working for the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs. The Chairman was General Powell, an Army officer, and I had been hoping to get back into OPNAV. I had 24 hours to make up my mind.

I called back, and people told me good things about the Chairman. I took the job and had a hell of a ride working during and after the Gulf War for General Powell—an extraordinary American. He didn’t make me as much of a joint officer as he would have liked, and I didn’t make him as much of a maritime officer as I would have liked, but it was a great job.

Nelson: What five books would you recommend to any naval officer?

Swartz: The first piece I’d recommend officers read is my paper “American Naval Policy, Strategy, Plans, and Operations in the Second Decade of the Twenty-First Century” (CNA, January 2017).

The next book I would recommend is John Lehman’s Oceans Ventured: Winning the Cold War at Sea (W. W. Norton, 2018). It is a case study of how to use naval power to help defeat a great power competitor. It also includes some great sea stories.

Next is Peter Haynes’ Toward a New Maritime Strategy: American Naval Thinking in the Post–Cold War Era (Naval Institute Press, 2015). His book is a great read on how the Navy thought—and argued internally—about strategy during the past quarter-century.

My fourth pick is James Rentfrow’s Home Squadron: The U.S. Navy on the North Atlantic Station (Naval Institute Press, 2014). Rentfrow talks about how the U.S. Navy first began to address the operational issues of the modern era, including some uncanny similarities to today.

And my fifth choice is Captain Wayne Hughes and Rear Admiral Robert Girrier’s Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations, 3rd edition (Naval Institute Press, 2018). All naval officers must be familiar with the data and views presented and issues raised, and this is the best, most-recent—and only—book that does that.

I also have to include Albert Nofi’s To Train the Fleet for War: The U.S. Navy Fleet Problems, 1923–1940 (Military Bookshop, 2010) and Ed Miller’s War Plan Orange: The U.S. Strategy to Defeat Japan, 1897–1945 (Naval Institute Press, 2013).

Nelson: You’ve written a lot over the years. How would you describe your research and writing process?

Swartz: First, I read or hear about something someone else has written or said about the Navy. Second, I get mad; I think the author is wrong. After I calm down, I reflect on whether I have a better answer (this sometimes takes a while). After that, I start to research it. And I research and research and research it to death. I often don’t actually come up with a final product. My friend, naval historian Tom Wildenberg, says I’m a “collector” more than an “analyst,” and he’s right.

Next, I realize I now know a lot but can’t seem to come to finality, and I worry no one will learn from what I learned, so I start making interim reports and shooting out drafts and holding workshops to get the word out. I get comments back on the drafts, which almost always require me to do even more research. Sometimes I finish and publish, but sometimes I don’t, and so I wind up recirculating drafts.

Part of the reason I don’t finish is because I read something else that gets me mad, and causes me to reflect, and I charge off researching that instead of finishing up the last piece.

Finally, I share. I keep circulating and recirculating old drafts for years, which stay alive and in play. Also, I circulate items I came across in my research. I’m “the Navy’s research assistant,” but I wind up publishing only a fraction of my own research in final form.

Nelson: You’ve worked for some well-known senior leaders in the military. Who impressed you the most or shaped you in ways you realized only later?

Swartz: Well, they all impressed me, of course. It was an extraordinary privilege to work for them, although they were all very different and we didn’t always agree. They were smart. They were dedicated. They were energetic. They had ideas they were trying to implement. They were imaginative. They were aggressive. But they had a personal touch and were kind and took an interest in me and in others. And they listened to what I thought and provided to them and occasionally acted on it.

Nelson: Some younger officers are skeptical that an essay can shape a senior naval leader’s thinking. Do you know of any essay written by a young officer that has shaped senior leaders’ thinking or changed the dialogue on an issue?

Swartz: Off the top of my head, I would cite Commander Guy Snodgrass’s study and article on officer retention (USNI Blog, March 2014), then-Lieutenant Sandy Winnefeld’s article tying Top Gun to the Maritime Strategy and showing how the strategy was shaping thinking among junior officers and others (Proceedings, October 1986); and Lieutenant Niel Golightly’s requiem for the Maritime Strategy (Proceedings, April 1990), which gave impetus to the development of “The Way Ahead” and “. . . From the Sea.”

Nelson: In 2009, author Tom Ricks said he had a hard time thinking of a naval officer who has been prominent in shaping U.S. strategy since 9/11. You made the case that the Navy did have strategic thinkers in the post–9/11 world. After 10 years, how would you answer your concluding question: “Does writing an influential article trump, say, Wayne Porter’s staff work on Global Fleet Stations or Doug Crowder’s staff work on the [fleet response plan] or a CNO decision to stand up [a Navy Expeditionary Combat Command] and revive riverine warfare, in the world of naval policy and strategy?”

Swartz: Not in the Navy it doesn’t. For example, read Peter Haynes’ Toward a New Maritime Strategy for a detailed discussion of the vociferous internal strategic debates leading up to 2007’s “A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower.” Commander Bryan Clark was an influential voice during Admiral Jonathan Greenert’s tenure as CNO, but his work was largely within lifelines, heavily influencing Admiral Greenert’s thinking and therefore thinking on policy and strategic matters. He publishes a great deal now that he is out of the Navy, but I believe he was more influential when he was in. Creating 2015’s “Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower” was done largely inside Navy (and Marine Corps and Coast Guard) lifelines. Strategic thought is expressed both inside and outside the lifelines. Taking external writings as the sole indicator of strategic thinking is simply wrong.

Nelson: Who in the Navy today has impressed you with their writing, speaking, or thinking on naval strategy and what we need to do going forward?

Swartz: Certainly, both recently retired Admiral Scott Swift and Captain Dale Rielage out in Pacific Fleet Headquarters. Their understanding of the importance of understanding Red, avoiding mirror imaging, and the need to get out and exercise at sea more thoughtfully. Also Admiral Jamie Foggo, in every job he’s ever been in. Vice Admiral Stuart Munsch has worked quietly and thoughtfully to inject naval strategic thinking into national strategic planning, and Rear Admiral Jeff Harley has ensured that the Naval War College continues to focus itself and its students on naval strategy, despite all the overwhelming pressures for joint approaches to everything. Bruce Stubbs, Director of Strategy on the CNO’s OPNAV staff, has been indefatigable in injecting strategic considerations into OPNAV planning. My boss at CNA, Dr. Eric Thompson, has done the same.

Nelson: In 2010 you coauthored a paper tracing the history of the OPNAV staff from 1970 to 2009, in part to understand how the staff’s organization did or did not support naval strategy. How should the next CNO reorganize the staff to focus on great power competition?

Swartz: I think the staff’s organization is okay. I believe, however, that in many cases the Navy’s assignment policies that detail officers to the OPNAV staff are deficient. The subspecialty system is broken, especially in the area of policy and strategy. More real experts need to be assigned to OPNAV’s shops—and the Navy has them. The Navy educates dozens of officers as strategists and pol-mil experts, in a variety of venues, but makes no special effort to ensure they are assigned for a tour in N50 or N51—let alone multiple follow-on tours. The same is true for other officer subspecialties.

This is a far cry from my experience on the OPNAV staff in the 1970s and 1980s, when I worked for flag officers and captains who had had multiple sea tours but also two, three, or four shore tours in OP-60. When I was writing a version of the Maritime Strategy in the 1980s, I was on my second tour in OP-60, with two master’s degrees in international relations. I worked for Captain Roger Barnett, who had a Ph.D. in political science, had been on an arms control delegation, had directed the Extended Planning Branch in OP-96, and had been deputy director of what is now N513 (International Engagement). Our uber-bosses—Vice Admirals Moreau and Lyons—were in their third or fourth tours in the strategy business, and on their way to four stars. There were numerous other officers in the division with similar backgrounds (including Hank Mauz, Joe Strasser, Jay Prout, Phil Dur, John Bitoff, Bill Center, Bill Fogarty, Dave Chandler, Jim Stark, Tom Marfiak, John Ryan, and other future flag officers). Their professional knowledge and insights were among several reasons why the Maritime Strategy had the power and influence it did.

Nelson: What issues do you think are underanalyzed in the Navy?

Swartz: I don’t know everything going on in the Navy, but I do think the Navy needs to pay attention to its bilateral relations with its sister services. Officers need to know and think a great deal more about what the Air Force does and can do for them, and need to think hard about what they could use the Marine Corps for, to cite two examples. I was a big fan of the original bilateral approach that spawned Air-Sea Battle and was sorry to see it swallowed up by the joint system.

Nelson: One of my favorite pieces you’ve written is “Understanding an Adversary’s Strategic and Operational Calculus: A Late Cold War Case Study with 21st Century Applicability” (CNA, 2013). What was that piece about, and what were some of your conclusions?

Swartz: It was an attempt to explain the virtues of sophisticated intel analyses using open sources, and to get operators and intel officers alike to pay more attention to open-source analysis. I learned this in the 1970s from Brad Dismukes, Jamie McConnell, Bob Weinland, and other CNA analysts who had cracked the code on Soviet Navy strategy years before their colleagues inside the intel community—using highly classified sources—did. Brad recently published a memoir on that experience. CNA’s current China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea “adversary analytics” analysts do classified work but still maintain the organization’s expertise and reputation for extraordinary open-source work.

Nelson: What advice would you give naval professionals who are trying to understand our competitors today—China and Russia, for instance?

Swartz: Pay attention to key open sources and develop cadres of linguistically astute analysts capable of interpreting those sources and explaining them to operators. Try hard not to mirror-image the competing powers or draw false historical analogies, or to focus inordinately on particular threats that justify particular programs and communities—and thereby miss the more important threats to the Navy and to the nation.

Listen to a Proceedings Podcast interview with Captain Swartz below: