Writing 120 years ago, just after the U.S. Navy burst on the world stage in the Spanish-American War, Alfred Thayer Mahan said one of the most critical numbers naval planners needed to keep in mind was 3,500. The 3,500 nautical miles (nm) from Hawaii to Guam are what he called the “standard distance” at the heart of naval planning for the United States.1 Mahan was making a narrow point about the importance of range to battleship design, drawing lessons from the 1898 “race to Manila” for designing a U.S. fleet that could reach the other side of the globe and defeat the enemy when it got there. Nevertheless, that same 3,500-nm distance remains a defining reality in the Pacific theater today, but few U.S. strategists fully appreciate its implications. In thinking about the challenges the nation faces in the Pacific, the Navy must consider Mahan’s yardstick at an intuitive level and also in the course of more deliberate analysis.

The Tyranny of Distance

Mahan’s standard distance is better known among sailors in the Seventh Fleet, planners stationed in Hawaii or Guam, and some policymakers in Washington.2 Indeed, invoking the “tyranny of distance” has become a staple of congressional testimony by Indo-Pacific Command leaders highlighting the difficulties of rapid response and the importance of forward deployment and foreign partnerships. But the challenge Mahan’s yardstick presents must be more than an Indo-Pacific Command talking point: It should be at the heart of force planning conversations on Capitol Hill and in the Pentagon and be better understood by the American people who pay for that force.

Distance is only one aspect of the operating environment in the Pacific, but low geographic literacy is a problem. In Mahan’s writings, the importance of careful study of geography and the spatial relationships that enable or inhibit concentration of the fleet’s combat power is a repeated theme. His “standard distance” may be a crude metric, but it highlights the geographic reality that must shape theater strategy and force development.

Planners who neglect this yardstick are ignoring one of the most important measures of the Navy’s effectiveness. At the expense of measuring the fleet’s reach, analysts focus on readiness levels, budgets, and total ship numbers. These metrics are essential to force management, but focusing debate on the number of ships obscures a vital issue: the ability of those ships, at the ranges of modern naval combat, to, as Wayne Hughes has argued, “attack effectively first.”3 A 355-ship Navy, or even a 600-ship Navy, is little better than a 280-ship Navy if those ships lack the ability to maneuver, sense, evade, and attack effectively at the ranges of naval combat in the missile age.

In 2015, Jerry Hendrix issued an indictment of U.S. force development decisions in relation to carrier aviation entitled “The Retreat from Range,” tracing the rise and fall of range as a critical requirement at key decision points.4 The same bureaucracy that once developed long-range aircraft such as the A-6 and S-3—and the F-14 that combined aircraft range with sensor and weapon range—now has produced a carrier air wing with less reach than its 1960s counterpart.

Carrier aviation is not the only area of force capability where distance has been underplayed. The U.S. surface fleet is well behind Russia and China when it comes to long-range antisurface warfare, although not for any lack of technical capability. This lack of offensive reach results from conscious decisions, such as that 25 years ago to remove the Tomahawk antiship missile (TASM) from the fleet.

Perhaps removing the TASM was a necessary cost savings of the post–Cold War peace dividend, and perhaps converting TASMs to land-attack missiles made sense for anticipated mission requirements of the 1990s. Perhaps successful targeting of enemy ships in the midst of “white” shipping was (and is) a daunting challenge at the TASM’s ranges. While deploying the Long Range Anti-Ship Missile (LRASM) in carrier air wings, and eventually in the surface fleet, will start to correct this drift, the longstanding lack of a TASM-class weapon, or something far more capable, is not the result of inefficiencies or technical barriers in the acquisitions process. If that process, and the thinking humans who guide it, considered and valued range, the fleet would have a weapon with real reach.

One fleet planning debate that occasionally has included discussion of distance is the future of the U.S. submarine force. Some have argued that there is room in the submarine fleet for diesel or air-independent-propulsion boats.5 Critics of this notion argue that only nuclear-powered submarines have the speed and endurance to cover the vast distances of the Pacific and stay on station.6 They claim any cost advantage would be offset by diesel boats’ limited speed and endurance: They would be slow in reaching the war zone and slow to maneuver and reposition in the fight. Further, their reliance on refueling at fixed bases—or a new generation of submarine tenders—would restrict the distance at which these submarines would be effective: a direct echo of Mahan’s reflections on the lessons of 1898.

But both sides have a valid point: The Navy needs a larger submarine force to sustain the nation’s enduring undersea advantage, but the cost of nuclear boats might make that prohibitively expensive. Whether or not a high-low mix or an all-nuclear submarine force is the right answer, placing more emphasis on the distances at which those submarines must fight will lead to better decisions.

The potential return of a Harpoon capability to the submarine force would be a positive reversal of another 1990s decision, but, as with TASM, it is not technology or resource limitations that have given the submarine force less offensive reach than rival navies.7

Critical Distance for the 21st Century?

The “wakeup” of Pearl Harbor has become the ready analogy for watershed moments imposed by unwelcome events. It shifted the Navy from a battleship-centric to a carrier-centric fleet, but it also shocked the United States into a new cartographic consciousness.

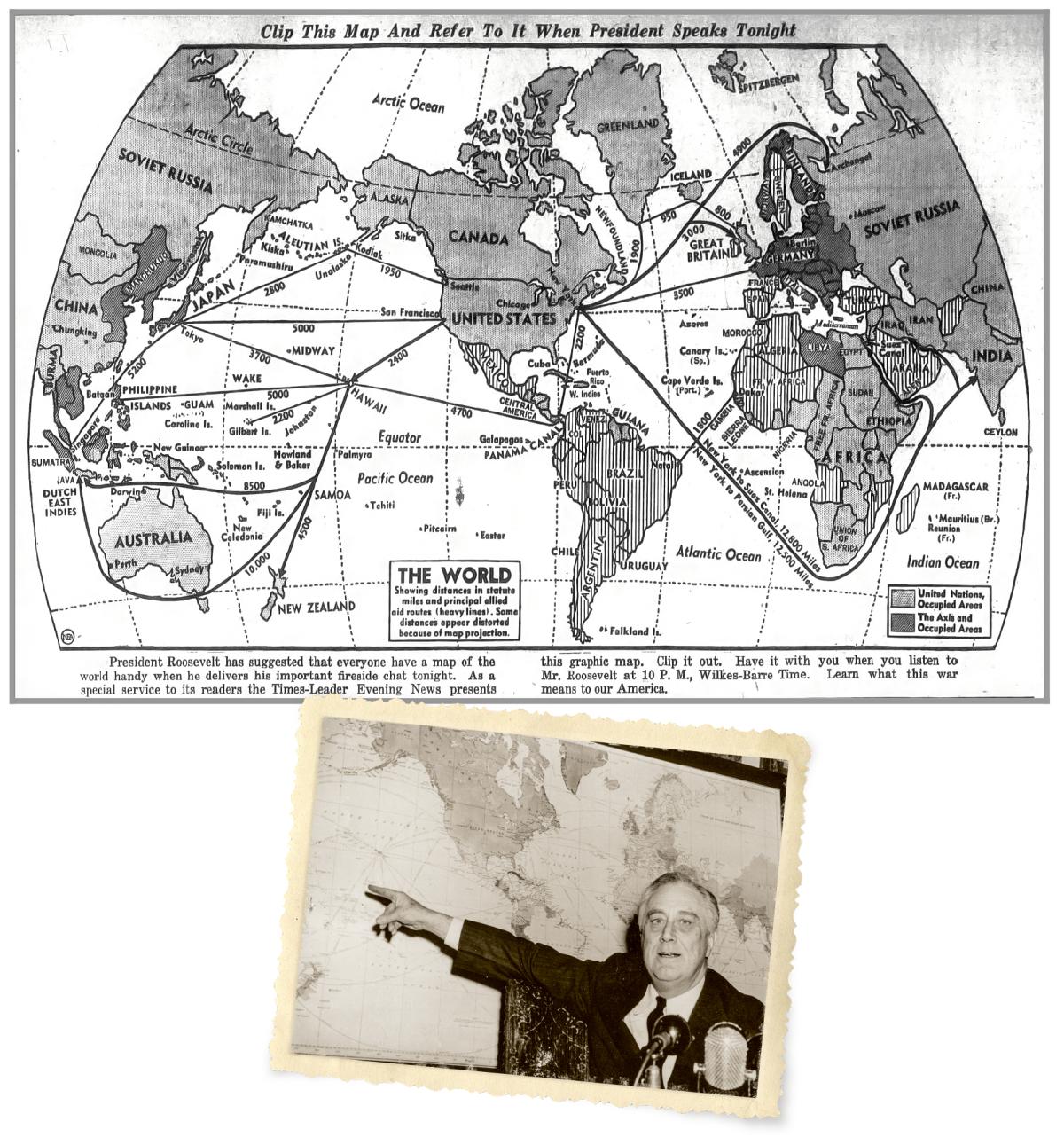

World War II sparked a renaissance of spatial thinking in the U.S. military and greater geographic literacy in the U.S. population. The war prompted the publication of sophisticated and inventive war maps and sold out atlases across the country as President Franklin Roosevelt asked the American people to follow along with his explanations of strategy in his radio addresses. Roosevelt’s 23 February 1942 address linked operational challenges of vast distance to grand strategy—not for the benefit of force planners, but for the public that would have to sacrifice to implement that strategy.8

The past 17 years of war and the emergence of new peer rivals such as China have not produced a similar increase in American geographic literacy. What will it take to get the non-professional to think about the vastness of the Pacific, to have every naval officer know the standard distances that govern fleet operations, or to return the fleet’s operational reach to a planning factor of the highest order?

And what might be the “critical distance” for 21st-century naval strategy and operational planning? There are many worthy candidates for a new Mahanian yardstick, but a strong case can be made for 1,000 nautical miles. This is roughly the distance from Shanghai to Tokyo or Manila, from Beijing to Okinawa or Hong Kong, from Singapore to Palawan, and from Jakarta to Fiery Cross Reef. It is a bit beyond the reported 810-nm (1,500-km) range of the Chinese DF-21D antiship ballistic missile—a worthy consideration, given the attention that particular weapon system has gained in the past decade. Given the possibility of new weapons entering the U.S. arsenal after a withdrawal from the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, the DF-21D range is comparable to that of a Pershing II missile, which retired Navy Captain Sam Tangredi has argued for adapting to a sea-based system.9 And deployment of the MQ-25 Stingray in its planned refueling role will push the air wing’s striking range close to 1,000 nm, depending on the mission profile and the range of the weapons it carries.10

But for the sake of argument, consider preserving Mahan’s original 3,500 nautical miles as the standard distance. The 3,500 nm between U.S. bases on Guam and Oahu are even more important today than they were for Mahan. A 3,500-nm-radius ring centered on Guam extends to the Aleutians, Xinjiang, and the Bay of Bengal and encompasses all of Australia. Mahan’s standard distance also is close to the critical distance in the best available case study of naval operations in the missile age: the Falklands War. The Royal Navy covered roughly 3,500 nm in staging force from Britain to the intermediate base at Ascension Island, and then deployed nearly the same distance from Ascension to the combat zone around the Falklands Islands.

Thirty-five hundred nautical miles is at the upper classification limit for intermediate-range ballistic missiles (IRBMs), but should the United States withdraw from the INF Treaty, it might derive great benefit from developing and deploying an IRBM system in the western Pacific. As Jacob Heim’s excellent RAND analysis points out, such deployments would be discontinuous and expensive and would pose a host of basing challenges, but the range this capability would bring could well outweigh the costs in a post-INF world.11

Finally, consider the possibility of applying Mahan’s 3,500-nm yardstick to the carrier air wing. Such reach would be an audacious stretch goal, but an aircraft with a 3,500-nm range is within the realm of possibility for existing flight decks, especially if that aircraft is unmanned and optimized for range. Imagine how different the conversation about the utility and survivability of the Ford-class carriers—to which the Navy is committed for the rest of this century—would be if those carriers could demonstrate their mobility and versatility nearly four times farther from their targets than they can today.

Range isn’t everything. Recruitment, readiness, training, damage control, mastery of the electromagnetic spectrum, and all the other challenges confronting the Navy are essential to avoiding some of the darker scenarios that might loom on the horizon, such as that laid out by Navy Captain Dale Rielage in “How We Lost the Great Pacific War.”12 And a myopic focus on range can crowd out thinking about and investing in effective “second-best weapons” such as mines. But, as Chris Nelson points out, U.S. mine warfare was at its peak effectiveness against Imperial Japan when mines could be rapidly delivered at Pacific ranges by air.13

The Pacific hasn’t gotten smaller since Mahan analyzed the geographic implications of the Spanish-American War and newly acquired U.S. possessions. Mahan’s geographic concept of the Pacific runs through the pioneering island studies of Major “Pete” Ellis and the strategists who crafted and continually revised War Plan Orange.14 U.S. ships no longer are powered by coal, and the nation relies far more on alliances and partnerships than in Mahan’s day. Nevertheless, his exhortation to know and value the critical distances in the Pacific remains essential.

The Navy must do more to inculcate an awareness of critical distance and must place greater emphasis on range, reach, and distance in force planning and strategy development. And all personnel should spend more time studying the distances in the Pacific and considering which essential strategic and operational challenges might dictate the “standard distance” for the 21st century. But until a better metric comes into focus, measure off 3,500 nm on a good chart of the Pacific and keep Mahan’s yardstick handy.

Author’s Note: The author would like to acknowledge Professor Kevin McCranie, Captain Dale Rielage, Mr. John Schaus, and Captain Max “Toto” Shuman for their helpful discussions and comments on this topic.

1. Alfred Thayer Mahan, Lessons of the War with Spain and Other Articles (Boston: Little, Brown, 1899), 41.

2. Mitchell Sutton and Serge DeSilva-Ranasinghe, “The U.S. 7th Fleet and the Tyranny of Distance (Interview with CTF-76 commander RADM Denny Wetherald),” Australian Naval Institute, 13 March 2016, https://navalinstitute.com.au/4329-2/.

3. CAPT Wayne P. Hughes Jr. and RADM Robert P. Girrier, USN (Ret.), Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations, 3rd ed. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2018), 27.

4. Jerry Hendrix, The Retreat from Range: The Rise and Fall of Carrier Aviation (Washington, DC: Center for a New American Security, October 2015).

5. ENS Michael Walker and ENS Austin Krusz, USN, “There’s a Case for Diesel,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 144, no. 6 (June 2018), and James Holmes, “Go Diesel, Scare China: Why the Navy Should Deploy Diesel Submarines to Asia,” The National Interest, 1 September 2018.

6. CDR Cameron Ajilani, USN, “U.S. Diesel Boats? Never Again!” Undersea Warfare (Winter 2018).

7. Richard Scott, “NAVAIR Reveals Sub-Harpoon Contract Award Plan,” Jane’s Missiles and Rockets, 17 December 2018.

8. Franklin D. Roosevelt, “On the Progress of the War,” radio broadcast, 23 February 1942 (Fireside Chat #20). Transcript and audio recording available at https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/presidential-speeches/february-23-1942-fireside-chat-20-progress-war.

9. CAPT Sam Tangredi, USN (Ret.), “/node/32644,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 143, no. 8 (August 2017).

10. “Interview with the ‘Air Boss,’” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 143, no. 9 (September 2017).

11. Jacob Heim, Missiles for Asia: The Need for Operational Analysis of U.S. Theater Ballistic Missiles in the Pacific, RAND Research Report RR-945.

12. CAPT Dale Rielage, USN, “How We Lost the Great Pacific War,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 144, no. 5 (May 2018).

13. CDR Christopher Nelson, USN, “Win with the Second Best Weapon,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 144, no. 11 (November 2018).

14. James R. Holmes and CDR Kevin J. Delamer, USN (Ret.), “Mahan Rules,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 143, no. 5 (May 2017): 40.