When the United States began building battleships in about 1890, it adopted—uniquely among the world’s battleship navies—two-story turrets for some them. The lower level carried the usual pair of heavy guns, with a pair of 8-inch guns mounted in the upper level. Smaller, quick-firing guns also were on board. All other navies carried their heavy guns in single-story twin turrets, with triple and quadruple turrets far in the future.1

Many naval experts argued that the most important battleship guns were quick-firing ones discharging explosive shells that could tear up an enemy ship’s unarmored structure.2 The advent of brass cartridge cases made quick firing possible. On firing, the cartridge case expanded to seal the gun’s breech. That meant there was no need for an elaborate breech mechanism, which took time to operate. After firing, the case cooled and contracted, so it could easily be extracted. The cartridge case had to be made very precisely; defects would allow firing gas to escape.

Manufacturing cases of larger and larger caliber seems to have been no problem for the United Kingdom and, almost certainly, France. In the 1890s, the United States still was a developing country with relatively less-sophisticated industry. About 1890, the largest size cartridge cases the United States could produce were for 4-inch guns. There may not seem much difference between a 4-inch and a 6-inch gun, but the weight of a shell is proportional to the cube of its caliber. For a 4-inch shell, the nominal shell weight is 32 pounds. For a 6-inch shell, it is about 100 pounds, making it the upper caliber limit for a hand-loaded gun. All heavy quick-firing guns fired at roughly the same rate, so shell weight determined the ability to pour explosives into a target.

These factors seem to have determined the choice of weapons for the first U.S. battleships, the Indiana class, launched in 1893. Their design was roughly contemporary with that of the British Royal Sovereign class, considered the best of the time. Where the Royal Sovereign had a single-caliber secondary battery of 6-inch guns, the Indiana (Battleship no. 1) had a few slow-firing 6-inch guns and four twin 8-inch turrets, in addition to the main 13-inch guns in two twin turrets. It seems fair to envision the 8-inchers as a way of providing firepower that might offer more volume than the ships’ very slow-firing 13-inchers. This secondary-battery combination was repeated in the follow-on Iowa (Battleship no. 4), which had four 12-inch heavy guns in twin turrets. The U.S. solution seems to have been unique.

The space between the two heavy turrets determined how many faster-firing guns a ship could mount. U.S. battleships devoted much of that space to two twin 8-inch turrets. That was crucial if, given their ability to tear up a target, the faster-firing guns were really the ship’s most important.

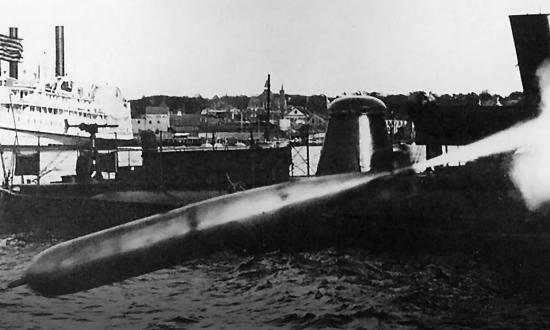

By the time the next design was being cast, the United States had advanced to 5-inch quick-firing guns. How could they be mounted in larger numbers without sacrificing 8-inch fire? In the next class—the Kearsarge—U.S. designers came up with an inventive solution. They moved 8-inch turrets to positions atop the main turrets. Two such raised turrets offered the same 8-inch broadside as the earlier two twin turrets on each broadside, at about half the weight. The 8-inch turret atop the 13-inch turret could not turn independently, but that was not considered a problem. It was assumed that a battleship would engage one enemy at a time. Space was thus cleared for more 5-inch guns.

By about 1896, U.S. industry was able to produce cartridge cases for 6-inch quick-firing guns, negating the usefulness of the slow-firing 8-inch guns. Designed before the Spanish-American War, the Illinois and Maine classes were similar in outline to contemporary British designs, armed mainly with heavy guns and quick-firing 6-inchers, plus much smaller guns to deal with attacking torpedo boats.

U.S. naval gunnery during the Spanish-American conflict was extremely poor, but sailors liked the 8-inch guns on board battleships and armored cruisers. The supposed performance of the 8-inch guns generated a demand they be revived for the next class of battleships. The 8-inch guns used in the war were rather different from those that would arm postwar ships; the latter offered much higher performance.

Congress was willing to spend considerably more per ship, so instead of displacing about 12,000 tons, the post–Spanish-American War battleships could displace about 16,000. That allowed for much more flexible designs. If 8-inch guns were required, should they be in two-story turrets or in the earlier arrangement with two independent 8-inch turrets on the broadside?

The designers punted. They produced two alternative designs, one with two-story turrets (plus one turret on each broadside) and one with two twin 8-inch turrets on the broadside. The 8-inch guns in the latter turrets would have high enough velocity to penetrate most battleship armor. In fact, the U.S. Navy also was building big armored cruisers equipped with these guns, which the service considered a sort of fast battleship (later ones had 10-inch guns). Both designs were adopted—the two-story type as the five Virginia-class battleships and the one-story type as the six ships of the Connecticut and Vermont classes. The Navy claimed that its strong sailors could handle 150-pound, 7-inch shells, which were too heavy for sailors of other navies.

The two Kearsarge-class battleships were not completed until after the Spanish-American War. Like earlier U.S. battleships, they had cylindrical turrets with vertical sides. To provide much barrel elevation, the turrets needed large ports. A young William S. Sims, assigned to the Kentucky (BB-6), considered her turrets a crime because a shell could pass through one of those openings to burst in a turret’s magazine. That was not the fault of her two-story arrangement, but the upper story certainly provided two more large gun ports. Subsequent battleships adopted the sloped-face turrets used abroad, which had much smaller ports.

Like the ones in the Kentucky class, the Virginia class’s two-story turrets trained as a single unit. That became much less attractive as single-caliber fire control was developed, at roughly the same time the ships entered service. However, the two-story turret may well have suggested to designers that placing more guns on the centerline would offer great advantages in terms of broadside weight for a given length of ship. That in turn may explain another great leap in battleship design: the use of superimposed, or superfiring, turrets in the South Carolina class, which succeeded the Vermonts, and in subsequent U.S. battleship classes. Superfiring turrets are single-story, single-caliber guns arranged along the centerline, with turrets toward the center of the ship elevated farther above the waterline than turrets nearer the bow and stern. Unlike the two-story turrets, superfiring guns are all of a single caliber and train and fire independently.

1. Surviving documentation of late-19th- and very early 20th-century U.S. warship designs is sparse, but this account seems to be the only one that fits the known facts.

2. In 1897, the U.S. 12-inch/35-caliber gun was rated at one round every 300 seconds and the 8-inch/35-caliber gun at one round every 120 seconds. A decade later, better loading practice reduced firing intervals to 30 and 51 seconds, respectively. In 1897, the U.S. quick-firing 6-inch gun was rated at 40 seconds per round, compared to 90 for a gun using bag ammunition (i.e., pre-quick-firing).