The development of the torpedo—the instrument of carnage that gave the submarine its potency—was long and tortuous, but a tangential musical connection would bring enjoyment around the globe.

Many inventors had tried to achieve a working self-propelled torpedo, but Robert Whitehead (1823–1905) and Giovanni Luppis (1813–75) would make the most promising advances. The former was an English marine engineer, and the latter had been an officer in the Austro-Hungarian Navy.

Whitehead’s father owned a cotton-bleaching business, and his grandfather was active in the Lancashire cotton industry when steam was beginning to galvanize the industry. Whitehead was apprenticed to a Manchester engineering company when he was 16. He was keen to see the world and subsequently worked in France as a marine engineer and in Italy as an adviser on the engineering needed for land drainage and silk weaving.

After moving to Trieste, he worked to refine and adapt marine steam engines. In 1856, he became the chief engineer of a company that built engines for Austro-Hungarian Navy warships in the empire’s Adriatic coastal town of Fiume (present-day Rijeka, Croatia).

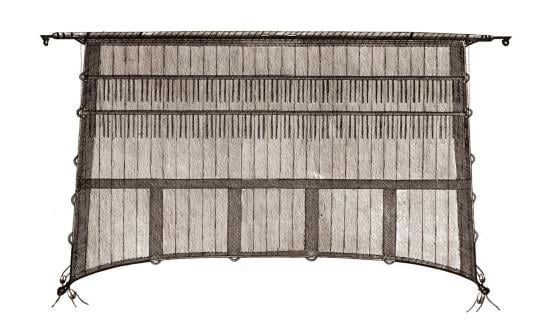

Eight years later, he began his association with Luppis, who had been trying to develop waterborne weapons. His inventions included an embryonic floating torpedo powered by a clockwork motor and packed with explosives. But it was unreliable and—hardly surprising—hazardous. The Luppis device inspired Whitehead to try to perfect a driverless underwater missile that would detonate on impact. It had to be practical, portable, and safe for use by its handlers. In 1866, he produced the Luppis-Whitehead torpedo, propelled by compressed air and fired from a tube. But it would not run at a constant depth, a problem he solved by adding a hydrostatic pendulum, the secrets of which he guarded for years.

The torpedo was a success and later adopted by sea services around the globe, including the Royal Navy. Having signed a contract with Luppis that gave him the rights on future sales, Whitehead became wealthy. Luppis, from an aristocratic family that had made money in shipping, died at age 62 in Milan, regretful, some said bitter, that he had signed away his rights. Now largely forgotten in the tides of history, he did not die entirely unrecognized. Austro-Hungarian Kaiser Franz Josef had bestowed on him the somewhat bizarre title of Baron von Rammer six years before his death.

In tracking the development of the torpedo, it would be remiss not to acknowledge endeavors in France, which at one stage led to pioneering submarine development, and in Britain, at the torpedo and mine school at the Royal Navy’s illustrious HMS Vernon. In the United States, the U.S. Naval Torpedo Station, established at Goat Island, Newport, Rhode Island, in 1869, also made a substantial contribution to torpedo development.

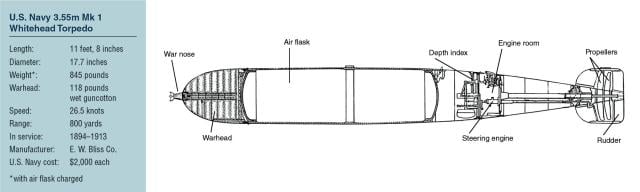

But the Whitehead torpedo was regarded as the most advanced, and by 1880, more than 1,400 of them had been sold to navies around the world. In 1891, Whitehead started the Whitehead Torpedo Factory at Wyke Regis, in southern Dorset, England, and opened negotiations with the E. W. Bliss Company of Brooklyn, New York, to produce torpedoes for the U.S. Navy.

Eliphalet Williams Bliss (1836–1903) is one of many noteworthy figures in early submarine and torpedo history. Growing up on a farm in Otsego County, New York, he showed a strong and early bent toward engineering. He started out at the famed Parker Gun Factory in Connecticut, noted for precision engineering and craftsmanship. He later established the E. W. Bliss Company, specializing in machining and metal production; some of its metal products were exported to Yorkshire, England, for use in the wool industry, while others were used in the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge. His company grew into a sizeable operation with some 1,800 employees.

In 1892, an agreement was signed in which the U.S. Navy would buy 100 Whitehead torpedoes from Bliss. The Navy, in effect, was giving its endorsement to the Whitehead torpedo. Bliss and other companies later would hugely benefit from torpedo and other armament contracts for the Spanish-American War of 1898, as well as for World Wars I and II.

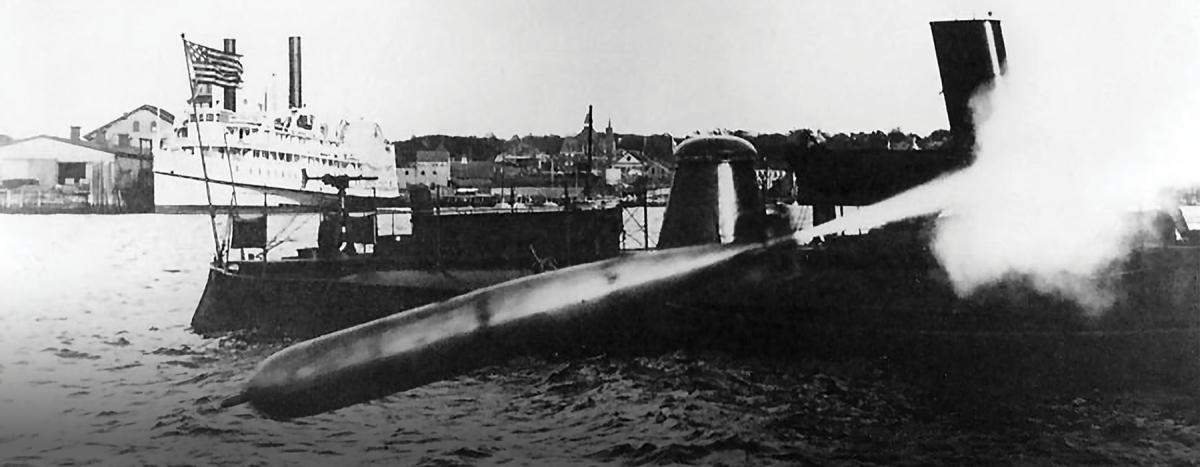

Myriad experiments were undertaken at HMS Vernon and Goat Island with different torpedo propulsion methods—electrical, chemical, and rocket firing—being tried. Bliss, meanwhile, conducted torpedo experiments in Peconic Bay, New York. But torpedo testing was always perilous. In one incident, a rogue torpedo shot through the hull of a small craft; mercifully, it had no occupants. Fifteen people attached to the Goat Island Torpedo Station would be killed in two 1918 explosions.

Though Whitehead’s torpedo was judged the best available, it was still flawed, as directional control remained a problem. Sometimes it worked; on other occasions torpedoes went rogue. A U.S. naval officer, John Adams Howell (1840–1918), is credited with developing a self-steering torpedo; its 128-pound flywheel, spun to 10,000 rpm before launch, creating gyroscopic properties for guidance. The U.S. Navy had ordered 50 of the torpedoes in 1889.

Inventor and former Austrian naval officer Ludwig Obry’s 1895 gyroscope could detect any deviation from a torpedo’s intended path and signal necessary changes to its rudders. Whitehead, always open to innovation and improvement, employed Obry’s innovations in his torpedoes before later using one of Howell’s designs.

Though the torpedo would herald mayhem, transforming the submarine into a predator that would change the course of maritime conflict, the Whitehead story also offers a pleasant aside.

Robert Whitehead’s daughter Agathe married a young Austro-Hungarian Navy officer, Kapitanleutnant Georg von Trapp. They had met in 1908, when he was at Fiume studying torpedoes and submarines. In World War I, he commanded submarines U-5 and U-14, but his naval career came to an abrupt end when defeated Austria had to surrender her coastal provinces to Yugoslavia and Italy. His life took another calamitous turn when Agathe died in 1922. Georg engaged a governess, Maria Augusta, to help raise the children. He later married her, and she bore him several children. Among other things, Maria taught the children to sing. Out of tragedy would spring joy.

It was not long before the musical talents of the family brought global fame as the Trapp Family Singers. Their story became the basis of the Hollywood blockbuster movie The Sound of Music.