Only twice during the Civil War did Confederates manage to break the stranglehold of the Union blockade. The first time is well-known: the land and sea assault on Union forces occupying Galveston, Texas, on 1 January 1863. The other, not known so well, came when the ironclads CSS Chicora and Palmetto State took on the blockaders off South Carolina’s Charleston Harbor on the 31st of that same month.

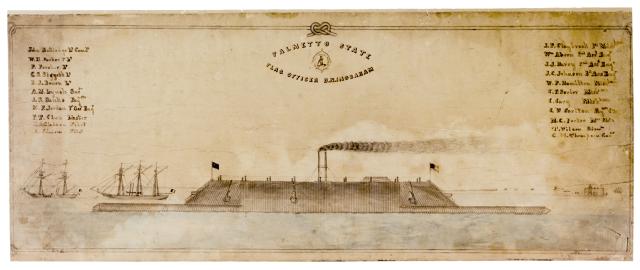

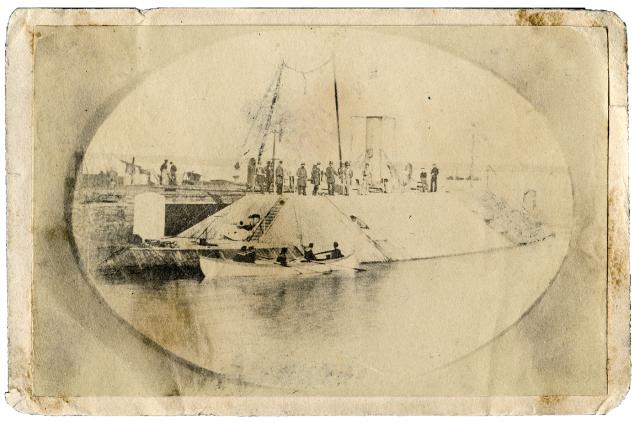

The two ships were testaments to Southern ingenuity and determination, constructed at Charleston mainly of materials salvaged locally. They were part of a class of six Confederate ironclads named for the first of the class, the CSS Richmond (also known as the Virginia II). The six sisters were built following the same casemate design as the CSS Virginia, which battled the USS Monitor to a draw at Hampton Roads, Virginia, in March 1862—but they were intended for a different strategic purpose. Instead of large, heavily gunned, seagoing ironclads that could take on the best of the Union Navy, they were smaller, basically harbor-defense gunboats and could be constructed with the South’s limited resources. Three of this class—the Palmetto State, Chicora, and Charleston—would form the Charleston Naval Squadron, but only two ever saw combat.1

The First Gunboats

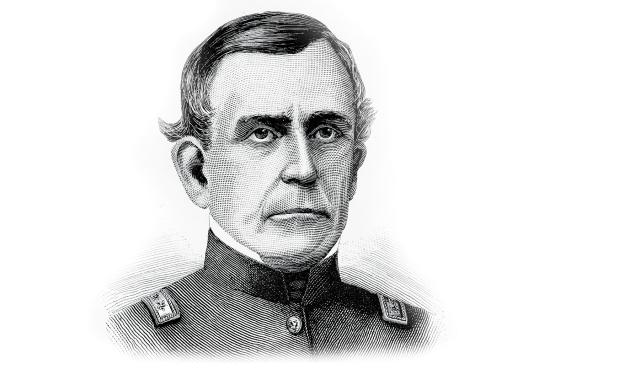

The Palmetto State and Chicora both were built in Charleston in 1862 under the supervision of Captain Duncan Ingraham. Charleston had no naval shipyards and no experienced shipbuilders, so amateurs built the vessels. Construction of the Palmetto State was in answer to a patriotic call in a Charleston newspaper in February 1862 for “the women of Charleston” to raise money to build a gunboat. James B. Marsh & Son won the contract and laid the keel within weeks. Meanwhile, the Confederate Congress appropriated money to build an ironclad at Charleston, and another contract was awarded to James M. Eason, who laid the keel in April. Competition was spirited between the two contractors, each vying to get his vessel in the water first.2

Construction, however, proceeded slowly because of problems securing building materials. Iron plate had to come from the Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond, the guns were part of the haul from capturing the Norfolk Navy Yard, and the engines were pulled from other ships. Both vessels had all the usual weaknesses of Confederate ironclads: They were underpowered and barely maneuverable. Both were outfitted with iron beaks in the misguided belief that they would do most of their damage as rams.3

Each ship was relatively compact—150 feet in length for the Palmetto State and 135 feet for the Chicora. The former was the heavier at 850 tons. Both drew about 12 feet of water. By comparison, the first CSS Virginia, which had been scuttled on 11 May, was 275 feet long and 4,000 tons with a battery of ten guns. The Palmetto State carried four inches of armor on her sides and two feet on the ends. The Chicora carried only two inches of armor all around. Since no Confederate ironworks could roll plates thicker than two inches, to achieve a four-inch thickness it was necessary to bolt two two-inch plates together, which was not as strong as a single four-inch plate.

The Palmetto State was armed with two 7-inch Brooke rifles fore and aft and a pair of IX-inch Dahlgren smoothbores on each side. The Chicora had six guns: IX-inch Dahlgren smoothbores fore and aft and four 6-inch, 32-pounder rifles in broadside. Their armament together barely equaled that of the Virginia.4

The crew of each gunboat, approximately 150 men, was a mix of experienced sailors and volunteers recruited from Army units. Some were veterans of naval combat at New Orleans and on the Mississippi River. Lieutenant Commander John Rutledge commanded the Palmetto State, and Lieutenant Commander John Tucker took the helm of the Chicora. Both were veteran seamen, but this was their first time to captain ironclads.5

Neither vessel was likely to strike fear into the hearts of the deep-water Union Navy. They were called gunboats because they were no match for ships-of-the-line or frigates. Because they were sluggish (top speed of 5 knots), they were vulnerable to enemy fire at their gunports and smokestacks, and their armor could not stand up to the heaviest Union guns. The pride of Charleston would have to depend on surprise to achieve their objective—breaking the blockade.

The Chicora won the race to the sea. She was launched on 23 August in an elaborate ceremony. A citizens’ committee selected the name Chicora (a legendary Native American kingdom or tribe early explorers searched for in what is now South Carolina), and she was commissioned a month later. The Palmetto State was launched in September and commissioned on 11 October. The choice of her name was left up to “the noble women in Carolina.” The usual sea trials had yet to be conducted, but for the first time the Confederacy had two ironclads at the same location ready for service.

As December turned to January, however, and the ships still sat at their moorings, citizens complained. One asked in a letter to the editor of the city’s newspaper, “Why is it that with gunboats at this port well-armed, manned, and officered and spoiling for a fight, we do not clear the blockade?” It was a good question.6

Preparation and into Battle

Any attack on the blockading fleet called for careful planning. General P. G. T. Beauregard might have been in command of Charleston’s defenses, but he could not command naval officers; all he could do was submit a request to them. Sending the ironclads into battle was Captain Ingraham’s call. Second, the two ships alone could not take on the Federal fleet. They required escorts or tenders, both to take possession of any blockaders they might capture and also because casemate ironclads were nearly blind when under way. The escorts could help prevent vessels with Yankee boarders from approaching. The lightly armed paddlewheelers Ettiwan, Clinch, and Chesterfield would fill the role of escorts.7

Union Rear Admiral Samuel F. DuPont, commanding the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, was aware of the shipbuilding at Charleston. Throughout the fall of 1862, he had begged Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles for ironclads, but the North was experiencing its own problems building the novel ships. Fortunately, DuPont’s intelligence reports in January 1863 said the Rebel gunboats were nowhere near ready to go to sea. That is why all was quiet off Charleston Harbor on the foggy night of 30 January. The Confederate plan was to attack under cover of darkness, taking advantage of the element of surprise. Ingraham would personally lead the little squadron, flying his flag from the Palmetto State.8

At approximately 2300, the two ironclads quietly weighed anchor and began moving toward the mouth of the harbor. Earlier in the day, their crews had greased down the casemates because it was believed this would cause enemy shells to glance off the sides. Any shoreside observer (spy) would have known they were preparing for action.

Timing of the attack was vital. The ironclads could cross the bar at the entrance to the harbor only at high tide. And the attack had to be coordinated with Confederate shore batteries so that in the dark they would not fire on the gunboats. After waiting at the bar for several hours, at 0440 the ironclads steamed quietly out of the harbor. For some unknown reason, their three escorts did not accompany them.9

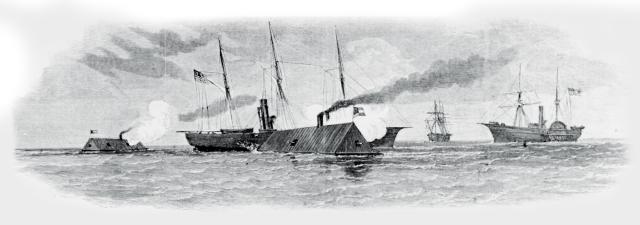

The two iron ships chugged seaward. Trying to navigate in the fog was useless; they literally blundered into the blocking fleet. The first vessel they encountered loomed up as a dark shape in the pea-soup visibility. She was the steamer USS Mercedita. Captain Rutledge ordered full-speed ahead, intending to ram the blockader. The ironclads were barreling toward her at three or four knots when the Mercedita’s deck officer sighted a dim outline approaching and ordered “All hands to quarters!” The captain joined them and hailed the mystery vessel: “Steamer ahoy! Stand clear of us and heave to! What steamer is that?”

Like a Freight Train

After a long pause, a reply came back: “This is the Confederate States Steamer Palmetto State!” The ironclad then slammed into the Union ship like a freight train, her iron bow driving deep into the hull of the opposing ship. Lieutenant Philip Porcher, commanding the gunboat’s forward Brooke rifle, fired a 7-inch shell point-blank into the Mercedita. It passed through the bowels of the ship, disabling the steam machinery before emerging out the other side and leaving a 5-foot hole.

The Palmetto State backed engines and pulled free of the Yankee, and Captain Rutledge hailed her, “Surrender or I’ll sink you.” The Mercedita’s captain sent his first officer over in a whaleboat to surrender. He was escorted to the wheelhouse, where a discussion of terms got under way while valuable time passed. Ingraham flatly refused to take the blockader’s crew aboard since she did not appear to be in imminent danger of sinking. Nor could he spare a prize crew, so he paroled the Union crew, putting them on their honor not to fight again until properly exchanged. At this point, Ingraham must have cursed the captains of his missing escorts. Eager to return to the fight, the Palmetto State steamed off to find her sister ship, which was strangely quiet.10

That was because after she split from the Palmetto State, it was another 30 minutes before Captain Tucker found an enemy to engage: the steamer USS Augusta. At 0540 the Chicora opened fire, sending a few rounds toward the Augusta before ever-so-slowly turning to take on a larger foe looming up out of the fog. She was the side-wheeler Quaker City, rapidly approaching with the clear intention of engaging the Chicora. At 100 yards, the Chicora fired her forward Dahlgren smoothbore then came around to fire a broadside. One of those shells exploded in the engine room of the Quaker City, which promptly turned tail and limped away.

Next, the side-wheeler Keystone State came on to engage the Confederates. Her skipper, Commander William LeRoy, had heard shellfire and guessed the blockaders were under attack. He ordered his ship forward and hailed the Chicora. When he received no reply, he ordered two ineffective broadsides fired at the mysterious vessel. In return, an incendiary shell from the Chicora’s forward Dahlgren shattered the Keystone State’s starboard wheelhouse and set the ship ablaze. LeRoy ordered his gun crews to cease firing and lowered his flag. Captain Tucker then ordered an officer and prize crew to board her, but before they reached the Union vessel, LeRoy discovered that his ship still had one good paddlewheel, so he opted to flee instead, a contravention of naval custom.

Meanwhile, the steamer USS Memphis, a former blockade-runner, arrived on the scene and, seeing the Keystone State’s predicament, tossed her a towline. Since the Keystone State had lowered her flag, this was dishonorable by the rules of naval warfare. But because the Memphis had not surrendered, she was perfectly within her rights to grab the disabled Union vessel and haul her to safety.

Meanwhile, the Keystone State’s captain ordered her flag back up, and she resumed firing. On board the Chicora, confusion reigned over whether the Yankee had actually surrendered or was still fighting. While the Southerners dithered, the two Union vessels steamed out of sight. Outraged over what Tucker called a “faithless act,” the Confederates opened fire again and gave chase but were too slow, another consequence of the ironclad’s weak engine.11

After an hour of combat, the Rebel ships had neither sunk nor captured a single enemy vessel. The Chicora tried to engage the other blockaders, but they all fled. Then Captain Tucker spotted a ship in the distance that was not fleeing. She was probably the Housatonic, a three-masted sloop mounting 21 guns, including a 100-pounder Parrott rifle. This might have been a more even fight, but before the two ships could close, Ingraham signaled his squadron to disengage and return to port. After waiting several hours at the bar for the water to rise, they reached home.

By default, the Palmetto State and Chicora held the field. The blockaders had not lost any ships, but three had been severely damaged, plus 27 men killed and 20 wounded.12

Blockade Lifted, or Not?

The battle at this point moved from the waters of the Atlantic to the halls of government, where diplomatic battles were fought. The burning question was whether the Confederates had broken the blockade to the satisfaction of the international community, which really meant the British, French, and Spanish. Ingraham reported confidently to Beauregard that he had scattered the blockaders and sunk several of them, information that the general relayed triumphantly to Richmond without confirming it.

Confederate Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin conveyed the news to the relevant consuls in the Confederate States.13 (Since the Confederacy was not officially recognized by any European power, it did not rate ambassadors.) Benjamin even sent a dispatch to that effect to Europe, where Confederate agents were arguing in several capitals for recognition. Back in Charleston, on the 31st, Beauregard thoughtfully put a steamer at the disposal of foreign consuls in the city so they could go out and see for themselves. Sure enough, they saw no sign of any blockaders.14

After consultation that evening, the three consuls jointly declared the blockade of Charleston broken. That meant the port once more was open to trade—at least for the next 15 days, which according to international law was the length of time that had to pass before it could be reestablished. Richmond joyfully seized on that verdict, announcing to the world that it had broken the blockade. Unfortunately, London, Paris, and Madrid, under pressure from U.S. ministers in each capital, refused to take the word of their consuls and declare Charleston an open port. Meanwhile, Washington did not wait 15 days to reestablish the blockade; four Union ships took up station off the port before the end of the 31st.

Celebration and Reaction

That did not keep the war-weary citizens of Charleston from “rolling out the barrel” to honor the heroes of the Palmetto State and Chicora. That not a single Confederate life had been lost in winning the glorious victory made the celebration all the more meaningful. Clear-eyed observers were not so sure. James Tombs, an engineer on board the Chicora, noted the obvious: They had not captured a single prize or sunk a single blockader. He questioned whether they had even raised the blockade; they sure hadn’t raised much “hell,” he grumbled.15

Spokesmen for the respective sides—General Beauregard for the Confederacy and Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles for the United States—not surprisingly had very different takes on what had happened. Welles proclaimed the blockade to be as strong as ever. Behind the scenes, however, he began assembling every Union ironclad he could to send to Charleston. Meanwhile, Beauregard crowed that Charleston was an open port. Welles’ pronouncements would prove to be more accurate.16

In the end, the spectacular sortie of the two ironclads had the opposite effect of what was intended. Instead of breaking the blockade, the attack awoke the administration of President Abraham Lincoln to the danger posed by Confederate ironclads and led to the strengthening of the blockade of Charleston; eight monitors and the armored steam frigate New Ironsides took station there. This was the most powerful force of ironclads ever assembled anywhere. Never again would the Charleston blockade busters venture forth to challenge the Union Navy. And having their own seagoing juggernauts stiffened the backbones of the embarrassed Union captains who had so precipitously abandoned their posts on the night of 30–31 January.17

That Battle of Charleston was not the end of its namesake squadron. Richmond shook up its command structure in March, transferring Ingraham ashore to command the Charleston Naval Station and putting Captain Tucker in command of the squadron. Commander Isaac Brown succeeded him the following year, and the little force was also augmented by two additions, the ironclads Charleston and Columbia. The keel of the Charleston was laid in December 1862, but the usual shortages delayed completion, and it was early 1864 before she was ready for service. Because construction had been financed with money raised largely by the ladies of Charleston, she was nicknamed “The Ladies’ Gunboat.” The Columbia’s keel was also laid in 1863, and she was projected to be a “monster,” 216 feet long, six inches of armor all around, and carrying eight guns. Both ships were significantly stronger than either the Palmetto State or the Chicora. The Columbia was launched on 10 March 1864, but during her sea trials she ran aground and cracked her keel. She was still aground in February 1865 when Major General William T. Sherman’s Union army approached.18

The Palmetto State, Chicora, and Charleston were defiant to the end. For more than two years they did their job, which was to hold the Union Navy at bay outside the harbor. They represented the time-honored naval doctrine of a “fleet-in-being,” a doctrine favored by weaker maritime powers for centuries, which stated that a naval force does not have to leave the safety of port to tie up disproportionate enemy naval forces. Posing an active threat is more important than risking combat at sea. In the end, Charleston fell, but not to Union naval forces; Sherman’s troops seized it from the rear. To keep his squadron out of enemy hands, Confederate Lieutenant Robert Bowen fired all three ironclads on 18 February. (Apparently, he did not consider the Columbia worth the trouble.) They burned magnificently until exploding and sinking at their moorings.

The three ships were next heard from in 1929, when the Corps of Engineers discovered them while dredging a creek that flowed into the harbor. Uninterested in trying to salvage them, the Corps removed their remains along with the sediment they lay in and dumped it all at sea.19

1. Kevin J. Dougherty, Ships of the Civil War, 1861–1865 (London: Amber Books, 2013), 44; Maurice Melton, The Confederate Ironclads (Cranbury, NJ: Thomas Yoseloff, 1968), 157.

2. E. Milby Burton, The Siege of Charleston, 1861–1865 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1970), 124–25; Paul H. Silverstone, Warships of the Civil War Navies (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1989), 205; Dave Page, Ship Versus Shore (Nashville, TN: Rutledge Hill Press, 1994), 131; Melton, The Confederate Ironclads, 153–54; James M. Merrill, The Rebel Shore (Boston: Little, Brown, 1957), 138–39; Robert M. Browning Jr., Success Is All That Was Expected (Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2002), 137.

3. Melton, 153–54; Browning, Success Is All That Was Expected, 136–37.

4. Silverstone, Warships of the Civil War Navies, 205; Melton, 153–54. Sources do not agree on the makeup of each ship’s battery. Cf. Browning, 137; Silverstone, 205; and Melton, 153–54. The descriptions here are based on a consensus.

5. Dougherty, Ships of the Civil War, 44; Melton, 154–55; Silverstone, 205.

6. Burton, The Siege of Charleston, 126, 128–29. Other sources are confusing on the launch and commissioning dates. Cf. Silverstone, Warships of the Civil War Navies, 205, and Browning, Success Is All That Was Expected, 137.

7. Browning, 138.

8. For DuPont, see Browning, 137. For Union problems, see John Niven, Gideon Welles (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973), 428.

9. Raimondo Luraghi, A History of the Confederate Navy (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1996), 209–10.

10. Melton, The Confederate Ironclads, 156–57; Browning, Success Is All That Was Expected, 138–40; Merrill, The Rebel Shore, 140.

11. Melton, 159. Browning, 140–41. For “faithless act,” see Burton, The Siege of Charleston, 131.

12. Melton, 159–60; Browning, 142.

13. Letter from the Secretary of State of the Confederate States to British consuls, regarding result of attack, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, series 1, vol. 13 (Washington, DC.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1901), 620–21.

14. Burton, The Siege of Charleston, 130; Browning, Success Is All That Was Expected, 142–43.

15. Thos. J. Scharf, History of the Confederate States Navy (New York: Rogers & Sherwood, 1886), 725.

16. Burton, The Siege of Charleston, 130.

17. Burton, 131.

18. For Charleston, see Melton, The Confederate Ironclads, 155,161. For Columbia, see Melton, 167–68. Also referred to in some sources as the “Ladies’ Iron-clad Gunboat,” there is some confusion over whether this name applied to the Palmetto State or the Charleston. Cf. Melton, 155, and Browning, Success Is All That Was Expected, 136 (fnt. 27).

19. Dougherty, Ships of the Civil War, 44.