In late May 1860, the American schooner Clotilde sailed from Whydah, on the West African coast (present-day Ouidah in southern Benin), for Mobile, Alabama. She was in a great hurry, having loaded perhaps 116 of what, had her departure been less hasty, might have been as many as 160 slaves, erstwhile captives of the King of Dahomey. For more than two centuries Dahomey’s kings had enjoyed a rich business—and would for a decade or so longer—selling their fellow Africans to all comers.

The pudgy Clotilde, 86 feet long and 23 feet abeam, under two masts and with a crew of 12, was commanded by Captain William Foster. Her owner was prominent Mobile businessman Timothy Meaher, whose gamble was he could smuggle Africans into the country past customs inspectors and in flagrant violation of long-standing U.S. law.

The importation of slaves into the United States and the United Kingdom had been illegal since 1807. The internal trade in slaves and slave ownership would be prohibited much later—in the United Kingdom in 1833, and in the United States not until the Civil War. That said, most scholarly estimates suggest that fully a quarter of the 12 million-plus slaves shipped across the Atlantic through the centuries were smuggled out of Africa after 1807 both to the United States and to Spanish and Portuguese colonies.

Laws aside, Meaher easily succeeded as a highly public scofflaw: In mid-July 1860, the New Orleans Sugar Planter and other Southern newspapers reported without commentary that the Clotilde had cleared the bar and anchored in Mobile Bay the week before, on 9 July. From there a steamboat “took the negroes on board and continued up the river to some unknown point,” where they were delivered to planters. Meaher kept 30 for himself.

Northern papers were not so matter-of-fact. The Newark Mercury and others editorialized:

The President and Cabinet recently made all sorts of promises to Congress that the laws for the suppression of the slave trade should be respected, and carried out to the fullest extent. . . . The crime is still carried on to an enormous extent, and many arrivals of vessels at Southern ports are those of slavers, landing their cargoes of stolen negroes upon our shores, and replenishing the supply of slaves in the South. Only on Monday last a cargo of one hundred and twenty four Africans were landed from the schooner Clotilde at Mobile . . . we are bound to believe, in the face and eyes of the officials of the Federal Government.

The Clotilde’s crossing and the delivery of her cargo were not unique, but they were historic. They appear to have been the last time that slaves from Africa were shipped into the United States. Nine months after the Clotilde’s arrival in Alabama, Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor and started the Civil War, abruptly raising the question of the legality of slavery in the United States for the painful, last time.

The West Africa Station

One source suggests the Clotilde had slipped her cables and gotten under way hastily from Whydah in late May 1860 because the watch had spotted sails on the horizon, possibly those of a Royal or U.S. navy ship on the West Africa Station, one enforcing the several British and U.S. laws against the international slave trade.

The U.S. Navy’s squadrons early in the 19th century typically were small formations—a frigate (not always; these big ships were expensive to build and costly to operate) and several sloops-of-war and schooners—operating in the Mediterranean and later in European waters more generally, in the North and South Atlantic, in the Caribbean and the West Indies, and beginning during Andrew Jackson’s presidency, in the East Indies. Their missions were traditional ones: suppressing piracy, protecting trade, transporting diplomats and other government officials, showing the flag, and occasionally lending muscle to bolster U.S. diplomacy.

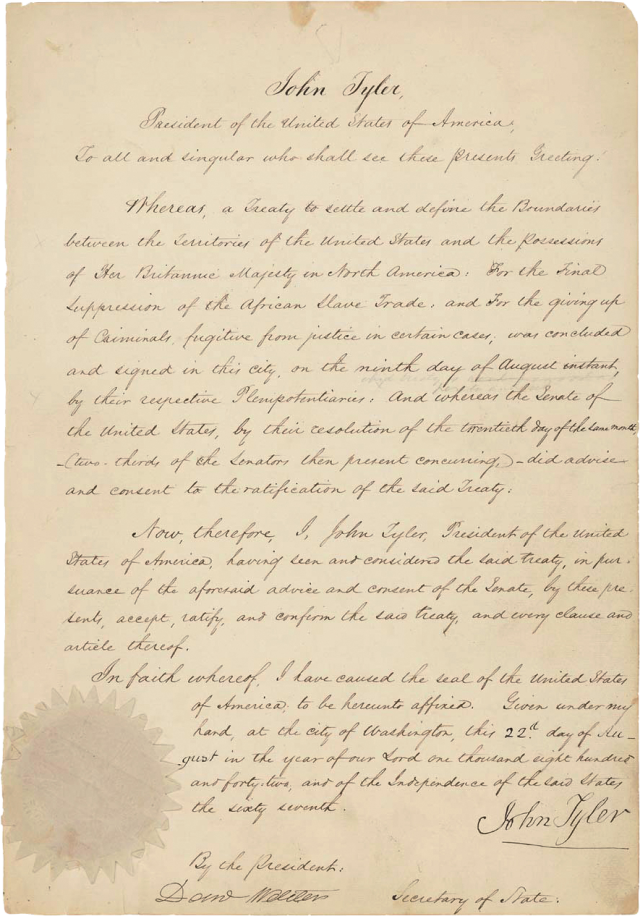

Not traditional was the mission of the U.S. squadron off West Africa during the 40-plus years it existed, off and on, between 1819 (when the enabling legislation was first passed) and 1861. It was most earnestly undertaken after November 1842 and implementation of the Webster-Ashburton Treaty until the start of the Civil War.

That treaty’s Article VIII provided that Great Britain and the United States each would maintain on the coast of Africa a “naval force of vessels” totaling at least 80 guns to enforce:

the laws, rights, and obligations of each of the two countries for the suppression of the Slave Trade, the said squadrons to be independent of each other, but the two Governments stipulating, nevertheless, to give such orders to the officers commanding their respective forces, as shall enable them most effectively to act in concert and cooperation, upon mutual consultation, as exigencies may arise, for the attainment of the true object of this article.

The treaty neatly dodged a problem that had bedeviled effective maritime enforcement. Although other trading nations had acquiesced to British bullying and agreed that the Royal Navy could stop and inspect their vessels, the United States had not. The determination of the United States not to permit any other country—in the shadow of the War of 1812, especially not Great Britain—to “visit and search” vessels flying its flag and carried on its registry opened a pore in the enforcement of laws against the slave traffic. Bringing the United States on board as an equal partner in the patrol solved that problem.

Equal partner legally, perhaps, but not equal in effectiveness. During the same period, the Royal Navy’s squadron might have caught some 20 times the number of slavers that its U.S. counterpart did, according to one source. Another source, historian Don Fehrenbacher, painted a no less bleak picture in his posthumously published The Slaveholding Republic. Over an extended period of time, he wrote, the U.S. squadron averaged grabbing one slaver a year; in the same period the larger squadron on the Royal Navy’s West Coast of Africa station caught 500 slavers and freed 38,000 Africans.

This disparity has been attributed to a lack of zeal on the part of the U.S. Navy, led most of the time between 1840 and 1860 by secretaries from the South and deploying ships often commanded by officers from Southern states. A more generous explanation seems to be that the U.S. Navy necessarily concentrated its efforts on those ships flying the U.S. flag, and although many slavers were American built and sailed to Africa from U.S. ports, few flew that flag off Africa and during the return crossing. The Royal Navy had much more game to hunt and deployed a much larger squadron to hunt it—27 ships in a representative year, 1852.

Ayers Negotiates for Land

Barely two months out of the building ways, in June 1821, the schooner USS Shark went into commission under her first commanding officer, Lieutenant Matthew C. Perry, at the Washington Navy Yard. She sailed in August for the Caribbean, followed by four months off West Africa, to lend her small heft to the new U.S. presence in those waters. Once on her new station, the Shark delivered Eli Ayers of New Jersey, agent for the five-year-old American Colonization Society, ashore and then joined for a short while the year-older and much lighter-gunned schooner USS Alligator on antislavery patrol.

Together with the Alligator’s commanding officer, Lieutenant Robert Stockton, Ayers quickly managed to extract from local kings rights to a 108-square-mile parcel of land, a slender coastal strip in western Africa on which a colony of freed American blacks eventually would establish Liberia and the city of Monrovia. That done, Ayers, then a month shy of his 44th birthday, died from one

or more of the diseases endemic to that famously unhealthy coast.

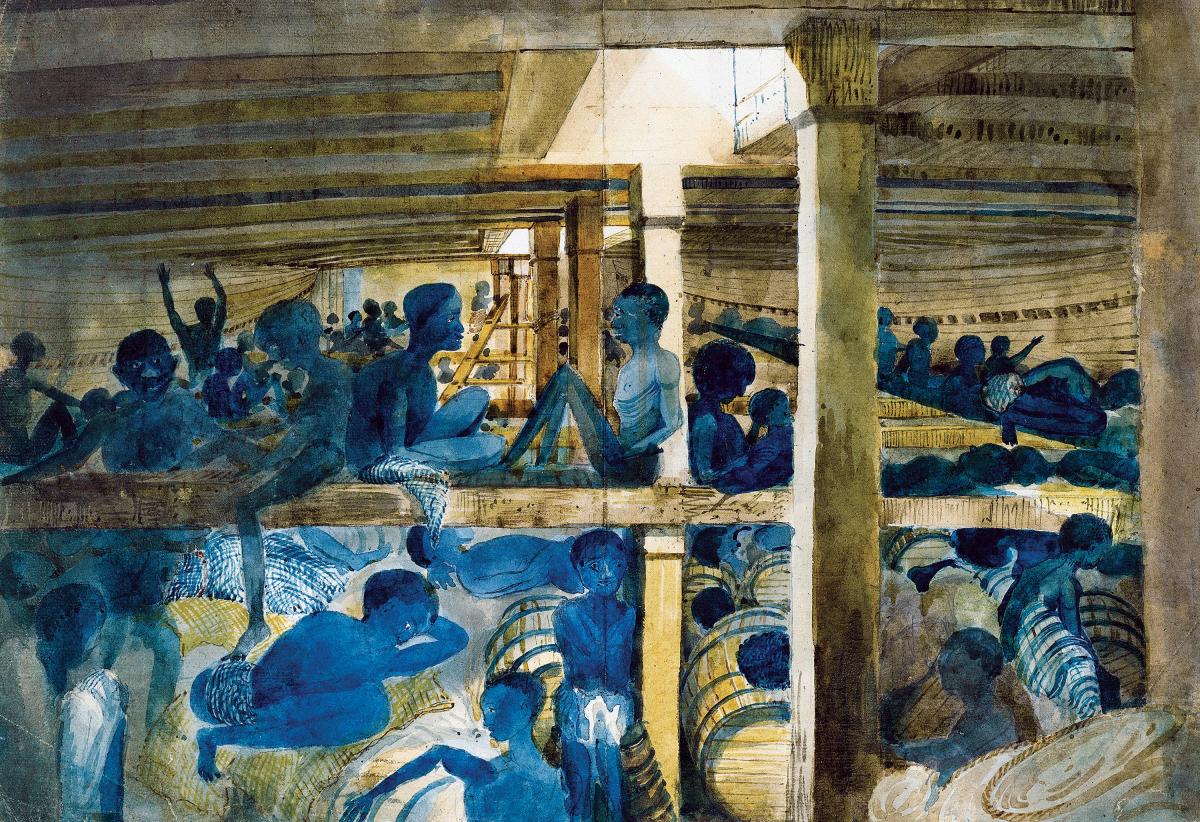

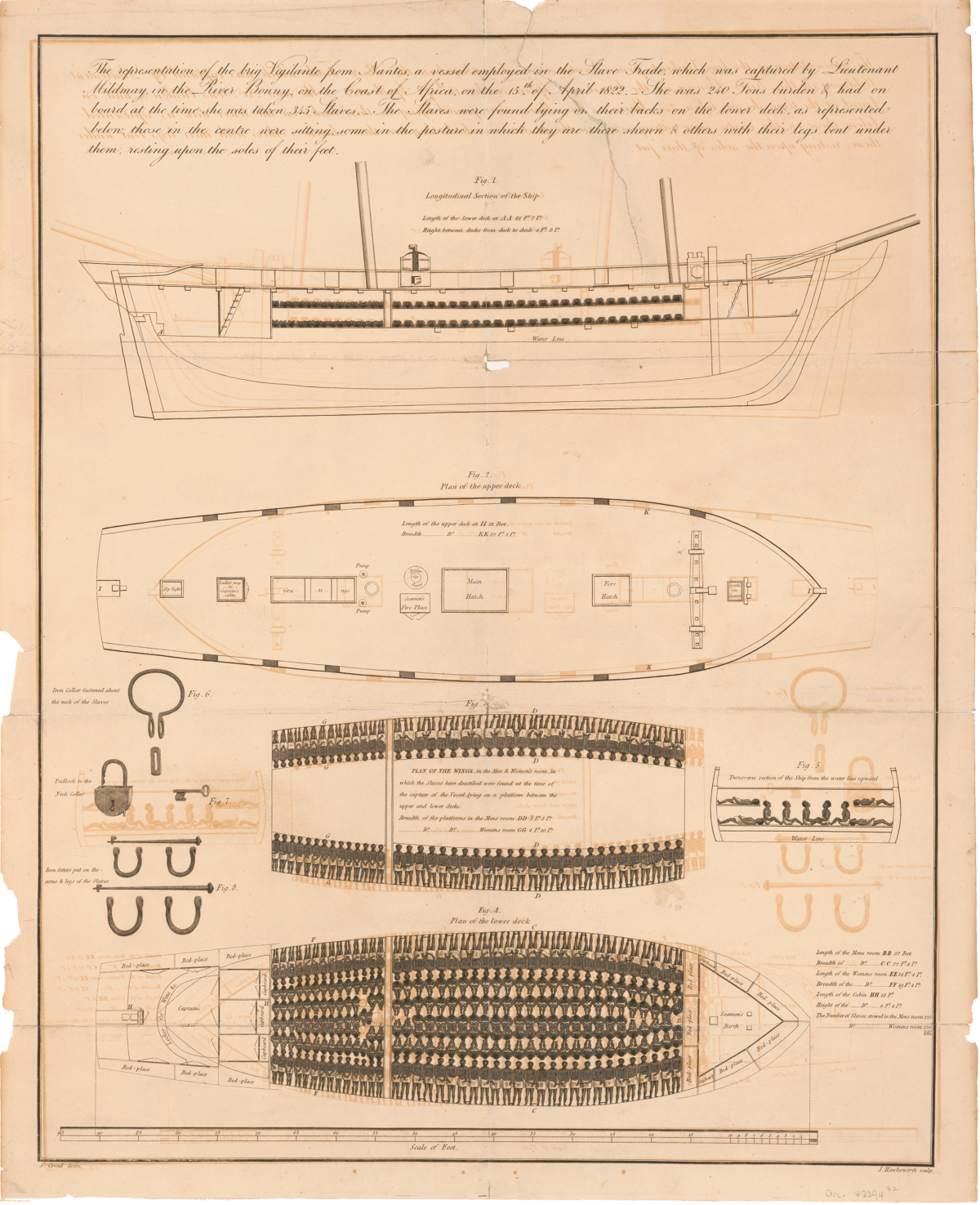

Exposure to fearsome and frequently lethal fevers, such as that which felled Ayers, was one reason why U.S. and British navy crews despised duty off West Africa. Other reasons included the long transits to and from station, epic boredom, enervating heat and humidity, no liberty ports, a strict prohibition against overnighting on shore (to avoid being exposed to vaporous “miasma” believed to carry disease), and the horrors routinely discovered in the hold when a ship finally intercepted a slaver and sent a boarding party on board. One such horror, cited by Fehrenbacher, was the discovery by a boarding party from the Shark in the small hold of the French slaver Caroline of 133 naked slaves, memorably described as resembling “Egyptian mummies half-awakened into life.”

Commander Lynch in Africa

Soon after the Shark’s commissioning, on 6 July 1821, Midshipman William F. Lynch joined her at the Washington Navy Yard from the frigate USS Congress, his first ship, for her impending cruise to the Caribbean and West Africa. He served in the Shark only through the end of the following January, time enough to have been on board during the schooner’s first months on her initial antislavery patrol of that decade.

Like other naval officers who served at sea during the interesting times of the 19th century, Lynch’s career had many highlights. In 1848, then-Lieutenant Lynch commanded the stores ship USS Supply in the Mediterranean, from which he went ashore to lead the Navy’s unlikely and historic exploration of the Jordan River and the Dead Sea in two small boats (see “Historic Ships,” pp. 58–59). Four years later, Captain Lynch returned to West Africa for most of a year after a decades-long absence, for a ground reconnaissance ordered on 25 October 1852 by Secretary of the Navy John Kennedy.

Sailing from point to point along the Liberian coast in the John Adams, Lynch repeatedly went ashore (so wrote Kennedy’s successor, Navy Secretary James Dobbin, in his annual report dated 5 December 1853) “for the purpose of ascertaining the localities affording the greatest facilities for penetrating the interior of the country.” The product of Lynch’s weeks ashore in Africa was a 60-plus-page annex to Dobbin’s annual report, complete with an appendix, sketches, and overlapping maps of the “Republic of Liberia” and “Maryland in Liberia.” The lengthy work is an enormously readable account of his progress on land, studded with economic data, and descriptions of exotic places and colorful native peoples and their lifestyles and speckled with improbable observations and unlikely explanations.

Travelogue done, Lynch finished his report with two professional observations. First, small and efficient steamers should supplant sailing vessels on the station. And second, officers needed to be incentivized to volunteer for service on the African coast. The macabre incentive he proposed was that a promotion to replace an officer who died while deployed should be permanent, not temporary.

In April 1861, Lynch resigned his U.S. Navy commission, curiously in view of his repeated antislavery views, to accept one in the Confederate States Navy. After honorable service during the Civil War, he died in October 1865 at age 64.

Operations Off Africa

Statistics and Lynch’s suggestions aside, while it was deployed, the small U.S. squadron off Africa had some notable successes.

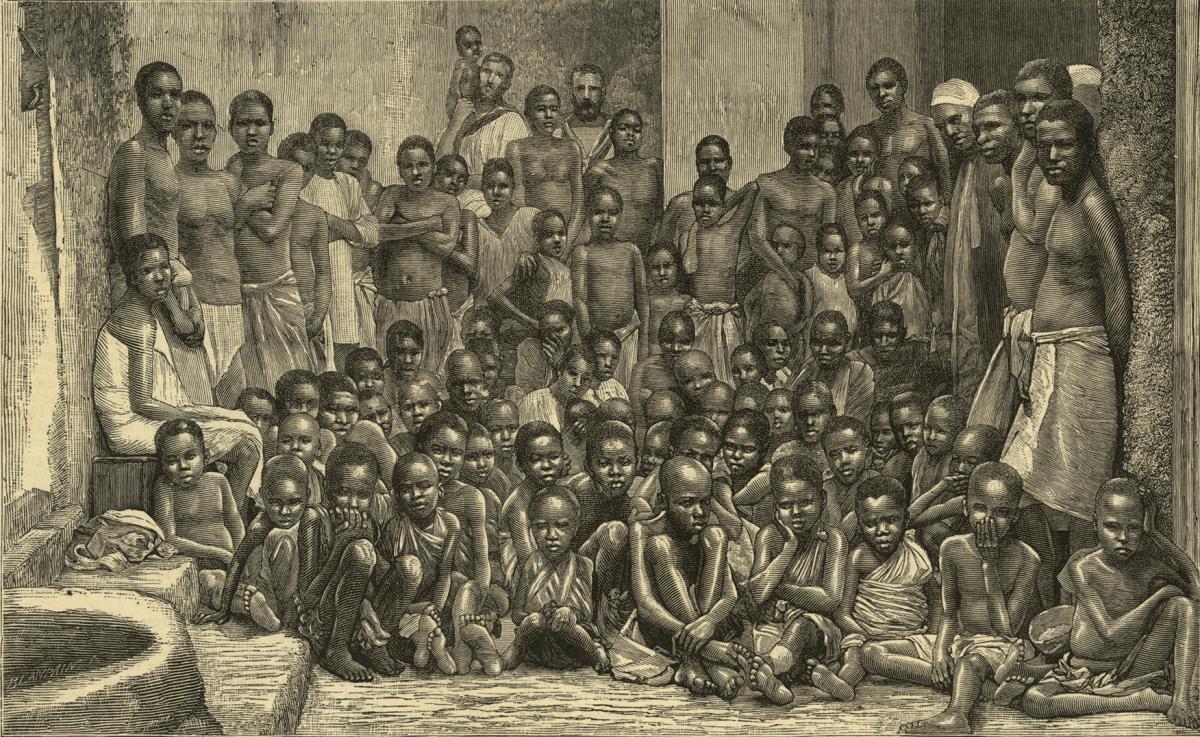

Late on 25 September 1860, the flagship USS Constellation ran down the Baltimore-built bark Cora 80 miles off the mouth of the Congo River and discovered 705 naked slaves “packed together like so many sheep” below deck. These unfortunates were put ashore at Monrovia, and the Cora, under a prize crew, sailed for Norfolk. In its 8 December story on the Cora’s capture, The New York Times boasted that “in the last six weeks 2,221 recaptured Africans have been sent to Monrovia,” all removed from the slavers Erie, Storm King, and Cora.

Soon after Fort Sumter first came under fire, on the night of 20 April 1861, off Kabenda on the West African coast, sailors from the sloop-of-war USS Saratoga boarded the Boston-based Nightingale, a ten-year-old former tea clipper.

Earlier, the Nightingale had left Boston for Liverpool with a cargo of grain, bread, and barrel staves. Out of Liverpool with a largely foreign crew and a suspiciously light load of dry goods on board, the Nightingale sailed for West Africa. The Saratoga’s boarding party discovered some 950 slaves concealed below her decks.

Stripping the Saratoga’s complement to create the Nightingale’s prize crew, Captain Taylor ordered Lieutenant John Guthrie to sail the former slaver to New York via Monrovia, where the rescued Africans were to be delivered ashore. Guthrie succeeded. That done, he arrived in New York on 15 June, despite the deaths from fever of several crew members en route (sharply paring both deck watches), and delivered the ship and her documents to government officials on shore.

Anglo-American Cooperation

On 4 March 1861, the day President Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated, the U.S. Navy had eight ships deployed on antislavery patrol off West Africa: the sloops-of-war Constellation, Portsmouth, and Saratoga; the screw steamers San Jacinto, Mohican, Sumter, and Mystic; and the stores ship Relief. All together 95 guns and nearly 1,000 sailors. Of the Navy’s remaining five squadrons afloat, only the Home Squadron (12 ships, 187 guns, and almost 2,000 men) was larger.

The five squadrons deployed away from home waters would soon have their ships recalled to join blockading squadrons fighting the war at sea against the Confederacy. Responding to this recall, between late September and mid-November 1861, all of the Africa Squadron’s ships except the sloop Saratoga were off station and back in home waters. Soon the Saratoga was ordered home, too.

Reflecting this reality, on 7 June 1862, President Lincoln proclaimed a treaty negotiated by his Secretary of State in April and ratified in May between the United States and Great Britain for the suppression of the African slave trade. In a sharp break with decades of U.S. policy, the treaty provided that U.S. Navy and Royal Navy ships could henceforth visit and search merchant vessels of the other power at sea off Africa or off Cuba in the slave trade or fitted out for it, thus permitting the interdiction of slavers at sea in the hemisphere even while Americans fought each other to death over the root issue.

Sources

lan R. Booth, “The United States Africa Squadron 1843–1861,” Boston University Papers in African History, vol. 1, Jeffrey Butler, ed. (Boston: Boston University Press, 1964).

David Eltis and David Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010).

House of Representatives, 53D Cong., 3d Sess., Mis. Doc. no. 58, ser. 1, vol. 50, xv–xvi, 11–14, 24.

Norman A. Howerton, “The U.S. Schooner Shark,” Oregon Historical Quarterly 40, no. 3 (September 1939), 288–91.

Zora Neale Hurston, Baracoon: the Story of the Last Black Cargo (New York: Amistad, 2018).

Ward M. McAfee, ed., Don F. Fehrenbacher, The Slaveholding Republic: An Account of the United States Government’s Relations to Slavery (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001).

Letters Sent to Naval Officers, and Letters Received from Commanders, Entries 6 and 520, RG 45, Collections of the Office of Naval Records Library, National Archives and Records Administration (hereafter NARA).

Log Books of U.S. Ships and Stations, Entry 118, RG 24, Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, NARA.