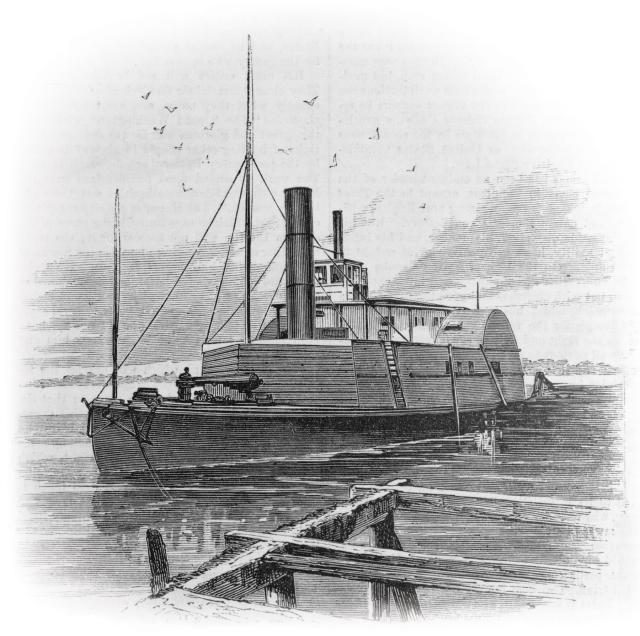

In the quiet morning hours of 13 May 1862, a pair of deckhands cast off all lines on board the side-wheel steamer Planter as she got up steam in South Carolina’s Charleston Harbor. The deckhands were slaves, most of them leased out to the ship’s owner to stoke the fires, work the decks, and haul the cargo as the vessel moved around Charleston’s waterways in the service of the Confederacy.

The ship herself was hired out to Brigadier General Roswell S. Ripley, the Confederate commander of the defense of Charleston. Used as a dispatch boat, cargo hauler, and troop transport, the Planter also was seen locally as the general’s personal ship. A few hours before dawn broke across the Atlantic horizon, however, the Planter had a new and different mission: freedom.

The only crew members on board the Planter, as she slipped her mooring below General Ripley’s headquarters and came about to head north toward the Cooper River, were the slaves. Charles C. J. Relyea, the ship’s captain, and the other two white officers who made up his wardroom had gone ashore that evening to spend the night with their families. While technically a violation of Confederate standing orders, this was not entirely uncommon, and the Planter’s “wheelman,” Robert Smalls, knew it, as did the rest of the crew.

With a hold full of cannon and military stores from a redoubt on the Stono River, which they had helped dismantle the day prior, the steamer slipped past the other vessels moored at Southern Wharf, and the guards walking the waterfront waved goodbye to the shadow-covered pilothouse.

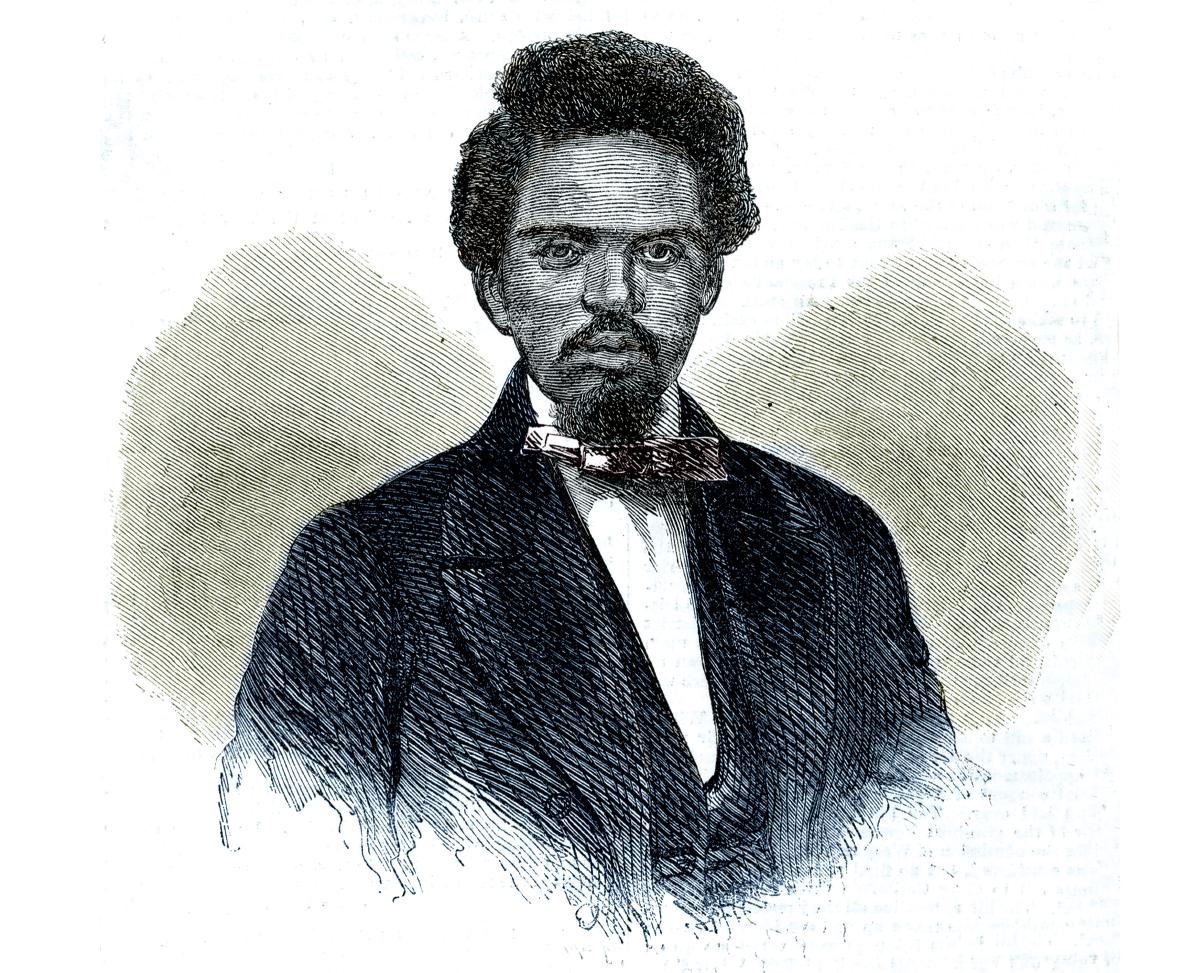

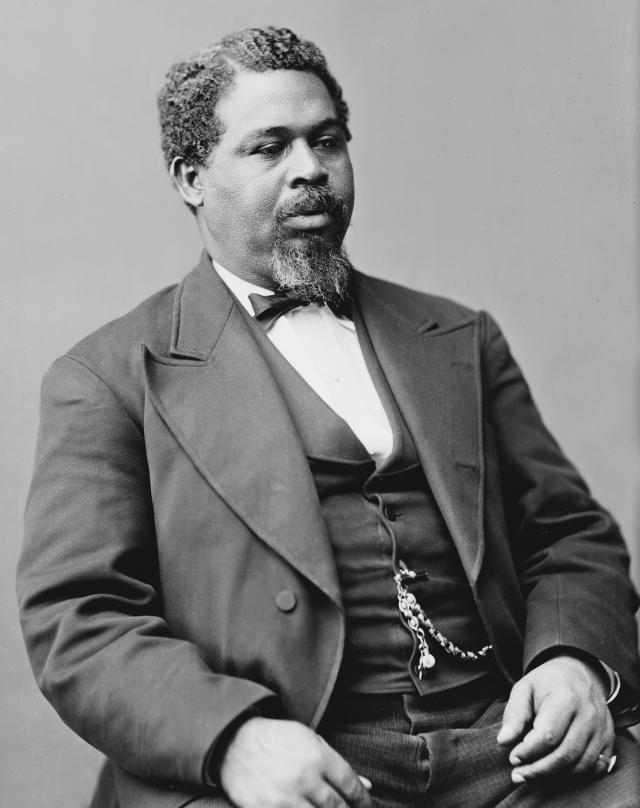

Smalls had been a member of the Planter’s crew since before the Civil War. Leased out in Charleston by his owner, Beaufort, South Carolina, planter Henry McKee, Smalls had been working the waterfront since he was a teenager. After first laboring as a waiter and then maintaining streetlamps, he started his maritime work as a stevedore and worked his way up the trades to become a trusted pilot and the rough equivalent of a noncommissioned officer as wheelman of the Planter. All the while, his salary went to McKee back in Beaufort.

In April 1861, when the Civil War had begun with the bombardment of Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, Smalls had stayed with the ship as she began working for the Confederacy. He piloted the steamer throughout the local area and took her as far afield as the coastal bays and waterways south of Charleston. He knew the Confederate minefields, defensive fortifications, and the shifting mud banks and sandbars like the back of his hand. He and his crew had begun talking about the possibility of escape, putting together a plan for something historians might consider somewhere between a mutiny and a naval cutting-out expedition.1

Escape: Now or Never

May 1862 was a tense time in Charleston. U.S. Navy Commodore Samuel Francis Du Pont had established a blockade of the Southern coast early in the war, and in November he had successfully seized Port Royal and the area around Beaufort. Establishing a U.S. Navy base of operations in the natural harbor south of Charleston, Du Pont had locked down a close blockade of South Carolina’s main seaport.

At the same time, the Navy and the U.S. Army in Beaufort had sent Henry McKee and his family fleeing from their home and had freed Smalls’ mother on the McKee properties. Du Pont and Major General David Hunter began planning for an assault on Charleston and testing the Confederate defenses. New Orleans fell to Flag Officer David Farragut in April, and by May Southern leaders were ready to place Charleston under martial law in preparation for the threatened attack.2

Smalls knew an escape attempt would become more difficult with the city placed under martial law. He and his men decided there was no time to lose.

They also knew when they decided to make their escape that they held valuable military resources, having just helped dismantle the Confederate defensive position on the Stono River near the mouth of Charleston Harbor. In addition, Smalls and his men had a wealth of intelligence about Confederate positions, strengths, and weaknesses, including the locations of minefields and the numbers of guns in defensive batteries. It was time to go.3

Running the Charleston Gauntlet

Instead of heading southeast toward the mouth of the harbor and the beckoning Atlantic, Smalls first guided the Planter north, away from the prying eyes of the guards around Southern Wharf and Confederate headquarters. Hiding in the hold of the steamer Etiwan moored on North Atlantic Wharf, where the Cooper River joined the harbor proper, were Smalls’ family—his wife, Hannah, their son, and his wife’s daughter—as well as the families of the other members of his crew. Despite the risk of heading deeper into Charleston Harbor, for Smalls and his men, escape with their families was the whole point and was built into the plan.

Slipping carefully alongside the Etiwan, Smalls held his ship in position without lines or a boarding plank as one of the moored vessel’s slave crew members helped the families leap aboard and join the escape. As the women and children climbed below to hide in the hold, Smalls brought the Planter about and headed south for the harbor’s main channel.4

It was 0325. The sun was climbing toward the eastern horizon, and a dull glow began to appear on the harbor. The steamer’s paddle wheel pushed the ship through the calm water, and she headed south toward the shipping channel. To the rest of Charleston, it appeared as if Captain Relyea and his ship were getting an early start to a full day of work.

Smalls had spent nearly a year in the pilothouse with the captain and his officers. As one of his shipmates took the wheel, he slipped into the captain’s cabin and donned Relyea’s uniform. He also picked up the floppy, wide-brimmed straw hat that the captain compulsively wore when on board and pushed it jauntily onto his head. He slipped into the shadows at the back of the pilothouse, appearing in the early morning light as the distinctive silhouette of the steamer’s captain diligently watching over his slave crew.5

Charleston Harbor was on high alert with the looming threat of Du Pont’s forces. Smalls and the crew of the Planter had to navigate past all the major defenses. He knew the locations of the minefields and which channels were open and which had been blocked with obstructions. He also knew the signals and codes as he passed each checkpoint, battery, and fortification on the harbor’s edge. The crew understood that, in addition to the chance of being fired on, if they were caught in the act on such an audacious mission, the men were sure to be executed, and the women and children would be split up and sold inland as plantation laborers.

As the paddle wheel churned the water at an easy cruising speed, Smalls maintained his cool, giving orders to his shipmate on the wheel and guiding the steamer past five different sets of guns. Despite the risk of going slowly, the ship moved without hurry in the morning breeze to avoid drawing attention. Smalls sounded the ship’s whistle, saluting the forts as the Planter passed, and leaned on the window with his arms crossed, as Captain Reylea always did, the straw hat pulled down low.6

At 0430 the Planter approached Fort Sumter, the last checkpoint before reaching open water and the promise of the U.S. Navy’s blockading squadron in the nearby Atlantic. Smalls put his hand on the lanyard and used the ship’s whistle to send the signal from the codebook announcing his intention to pass out of the harbor. Sumter’s lookouts, perhaps assuming that General Ripley could be on board on an inspection tour, signaled “all right,” and the Planter passed close under the fort’s guns without the slightest indication of trouble.

By the time the sentries realized something was amiss, the Planter was out of range of the fort’s guns. The Confederates signaled their battery on Morris Island to open fire, but it too was out of range, and the rounds fell short of the ship, whose paddle wheel now was spinning at flank speed. Smalls and his crew had escaped.7

Onward to Onward

But they were not yet in a position to celebrate. They were rushing at full steam, in a stolen Confederate warship, with Rebel guns firing behind them, toward the ships of the U.S. Navy. The closest vessel to the Planter’s approach was the blockader Onward, commanded by Acting Volunteer Lieutenant J. F. Nickels. She lay at anchor on what otherwise had been a quiet night, the crew beginning to awaken for another day on blockade duty.

The Onward, a clipper ship built in 1852 for the merchant trades, had run cargo between New York, Boston, and San Francisco prior to the war. Purchased by the Navy, which was desperate for blockaders in 1861, she had been outfitted with eight 32-pounder guns and a crew of 103 sailors and placed under Nickels’ command. As dawn broke, the Onward’s lookout spotted an enemy ship rushing toward them, and word was quickly passed to the commander. Nickels ordered his men to quarters.8

Since the Onward was at anchor, had no steam engine, and the crew was ill-prepared to get her sails up and get her under way, Nickels ordered deckhands to haul on the cables of the spring anchors. The ship rotated on her anchorage as the rest of the crew manned the four guns of her portside broadside and prepared to fire at the oncoming steamer.

As the tense moments ticked by, and Nickels looked westward in the growing light, he noticed an oddly shaped flag flying and later wrote in his report, “I discovered that the steamer now rapidly approaching, had a white flag set at the fore.”9 He called for his men to stand down from their guns. Smalls’ crew, as they realized the danger they were rushing into, had hoisted Captain Relyea’s white bedsheets into the air. The gun crews of the Onward remained at their stations, but Nickels allowed Smalls to maneuver his vessel alongside.

The volunteer lieutenant was shocked at what he found once he swung over his ship’s gunnel and onto the deck of the steamer. The crew was made up entirely of slaves. The women and children had come up on deck, embracing the men in tears as sailors from the Onward watched in surprise. Nickels sent one of his men for a flag, and when he returned he went to the yardarm and hauled down the makeshift white flag, replacing it with the American flag. Smalls and his crew cheered and wept as they saw the Stars and Stripes unfurl in the lazy morning breeze.10

From Contrabands to Crewmen

Nickels hastily wrote his report of the incident and put together a small prize crew, then dispatched the Planter to rendezvous with the side-wheeler gunboat Augusta. From on board the Augusta, Commander E. G. Parrott commanded the small group of ships that enforced the blockade at Charleston’s entrance. After only a brief conversation with Smalls, he wrote out a quick report and ordered an acting master to accompany the Planter directly to Admiral Du Pont at Port Royal. His report assured the admiral that “the very intelligent contraband” Robert Smalls brought with him valuable intelligence.11

For more than a year, U.S. forces had struggled with how to adapt to the influx of “contraband” slaves who were coming under their control (they were considered “contraband of war” in that they were property used to support the enemy’s war effort). Some officers, such as Du Pont and Hunter, believed these men and women were on the path to true freedom and the men should be given the opportunity to join the U.S. Navy and Army. Others disagreed.

But the practical reality was that naval commanders were in a bind; they were experiencing a personnel shortage while attempting to keep the ships at sea in their massive blockade of the Southern coast. Because free blacks had a long history of service with American naval forces and maritime trades dating back to the Revolution, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles had authorized captains to enlist contrabands in their crews—in essence creating an integrated force. While politicians debated, in the exigencies of wartime the Navy largely had been left to set its own racial policy.12

When the Planter arrived at Port Royal, Smalls was taken almost directly to see Samuel Du Pont. The Navy’s commander of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron was astonished. After hearing the story of the Planter’s escape, and once Smalls had shared with him the newspapers his crew had brought out of the harbor with them as well as the charts and codebooks, Du Pont wrote his report to Secretary Welles. The mission itself was nothing short of heroic, and Du Pont wrote that “[t]he bringing out of this steamer, under all the circumstances, would have done credit to anyone,” including white naval officers.

He continued that “Robert Smalls . . . is superior to any who have come to our lines, intelligent as many of them have been. His information has been most interesting and portions of it of the utmost importance.” There was no doubt in the flag officer’s mind that what had been accomplished was remarkable, and he told Welles that he believed Smalls and his crew not only should be honored, but also should be given prize money from the “capture” of the Planter.13

Courage Under Fire

Du Pont went one step further, making Smalls a pilot in the service of the U.S. Navy. It was clear to Du Pont that the man’s knowledge of the waters surrounding Charleston would make him enormously valuable. Du Pont also offered the rest of the Planter’s crew the opportunity to enlist, and most of them appear to have taken him up on it. The women and children moved into the camps being built at Beaufort to support the growing population of escaped slaves.

Smalls returned to the Planter as her pilot—retaining a civilian position rather than formally joining the Navy. Du Pont realized that, had Smalls enlisted, the naval hierarchy would not have allowed him to hold the important positions that the squadron needed him in, particularly based on his skill as a mariner and navigator and his knowledge of the surrounding waters.14

Barely a month later, Smalls was in combat with the U.S. Navy for the first time. Piloting the Planter, with a detachment of the 55th Pennsylvania Regiment on board and in the company of the U.S. gunboat Crusader, Smalls helped lead an amphibious raid on the Confederate camp at Simmon’s Bluff. It was the first of several times Smalls made it into Du Pont’s dispatches back to Secretary Welles.15 Through the remainder of the war Smalls was in 17 combat engagements and repeatedly was noted for his cool head and bravery.

In 1863, during the failed assault on Charleston Harbor, Smalls served as pilot of the ironclad Keokuk, which took a beating in a heroic gunnery duel with Fort Sumter.16 Smalls became a national figure, a hero in the newspapers of the North and a villain in Southern writings. In the summer of 1862, he had visited Washington to help make the case for allowing wider black enlistment, as well as formal emancipation. On that trip, he met with President Abraham Lincoln in the White House.

‘. . . History Will Delight to Honor’

Robert Smalls went from being slave to sailor to combat veteran to political leader to American hero by the end of the Civil War. But most important, he was a free man. He and his crew eventually were granted prize money by Congress, and it afforded him the financial security after the war to purchase the McKee house, where he had grown up as a slave in Beaufort.

Unfortunately, knowing that the money would go to escaped slaves appears to have offered naval officers a way to save money for the government. The officers assigned to survey the Planter lowered her value significantly, making it inexpensive for the Navy to purchase the vessel but also cheating Smalls and his men out of a significant amount of what they were owed.17 Smalls entered the newspaper business and politics after the war. He was elected to the South Carolina legislature, and in 1874 he was elected to the U.S. Congress as the representative for his home district in Beaufort.

Following his escape, the New-York Daily Tribune had written that, regardless of his skin color, Smalls was “a hero—one of the few History will delight to honor.”18 And yet, despite the laudable works of recent historians cited in this article, today his name is not widely known among the general public—nor in the U.S. fleet. There never has been a USS Robert Smalls. His story does not appear in most of the histories of the 19th-century Navy. Is it because he never formally enlisted in the U.S. Navy? Is it because of race? Whatever the reason, the historical record speaks for itself, and we should all remember Congressman Smalls and his place in American naval history.

1. Andrew Billingsley, Yearning to Be Free: Robert Smalls of South Carolina and His Families (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2007), 34–42.

2. Craig Symonds, The Civil War at Sea (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 147–49.

3. “Services of Robert Smalls,” House Executive Document 1546, 54th Congress, 1st Session, 2.

4. Cate Lineberry, Be Free or Die: The Amazing Story of Robert Smalls’ Escape from Slavery to the Union (New York: St Martin’s Press, 2017), 21–22.

5. “Report of the Committee on Naval Affairs,” 23 January 1883, House Executive Document 1962, 47th Congress, 2nd Session, 2.

6. “Report of the Committee on Naval Affairs,” 2.

7. “Services of Robert Smalls,” 2.

8. “Onward I (Clipper Ship),” Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/o/onward-slipper-ship-i.html.

9. J. F. Nickels to E. G. Parrot, 13 May 1862, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, series 1, vol. 12 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1901), 822.

10. Lineberry, Be Free, 72–73.

11. E. G. Parrott to Samuel Du Pont, 13 May 1862, Official Records, series 1, vol. 12, 821–22; Parrott to Acting Master Watson, 13 May 1862, Official Records, series 1, vol. 12, 822.

12. Joseph P. Reidy, “Black Men in Navy Blue During the Civil War,” Prologue 33, no. 3 (2001), www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2001/fall/black-sailors-1.html.

13. Samuel Du Pont to Gideon Welles, 14 May 1862, in “Services of Robert Smalls,” 3.

14. Lineberry, Be Free, 93

15. Lineberry, Be Free, 103–4.

16. Billingsley, Yearning, 78–81.

17. Lineberry, Be Free, 89–91.

18. “Robert Smalls,” New-York Daily Tribune, May 20, 1862.