As the potential for a lethal and complex conflict in the Pacific grows, it is more important than ever the U.S. Navy intensively trains to defeat the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN). However, live-fire training is expensive and logistically challenging to safely conduct. And while events such as the widely commended Naval Surface and Mine Warfighting Development Center “Live Fire with a Purpose” are effective, they do not generate the volume of fires desired. Similarly, while fleet synthetic training provides complex scenarios, it does not capture the entire operating environment. Therefore, neither live-fire training nor synthetic events can provide a comprehensive training solution.

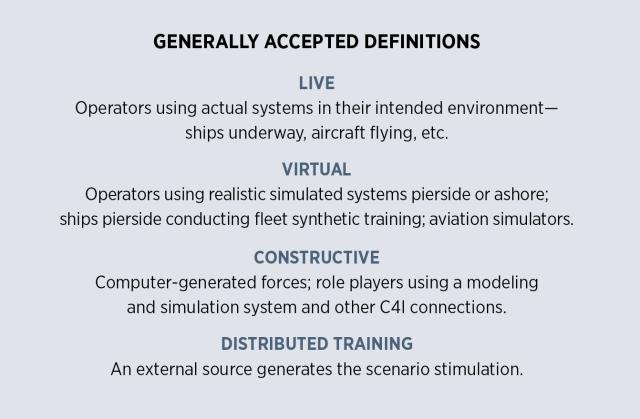

A live, virtual, constructive (LVC) hybrid or blended training environment can be the solution. LVC is not a specific system—it blends various systems, networks, and environments to enhance live training. Since 2016, LVC has been the preferred option for high-end integrated training and is rapidly expanding to all phases of the Fleet Response Training Plan (FRTP).

The LVC Appetite Grows

Since 2016, LVC-enhanced exercises have become a major part of all strike group and amphibious ready group integrated phase training exercises. LVC is further expanding into Surface Warfare Advanced Tactical Training and forward-deployed exercises, such as Valiant Shield and Talisman Saber in the western Pacific. Furthermore, most vision statements and policy documents in the past few years, such as the Naval Aviation Vision 2030–2035, articulate that LVC capabilities are critical to facilitate the required number of training events (reps and sets) against a credible opposing force while mitigating fiscal, geographic, and operations security constraints.1 In April 2023, both the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) and Commandant of the Marine Corps emphasized the need for multidomain LVC training at the Sea-Air-Space convention. And specific to Indo-Pacific Command, the Pacific Multidomain Training and Experimentation Capability seeks to connect U.S. and coalition forces across the region in LVC training.2

LVC Versus Live Training

Presenting LVC scenarios to the training audience can come in many forms. During “live” training, ships “shoot” constructive missiles but generally the action is observed only on the launching platform and kill confirmation only determined in debrief. Within LVC, however, inbound missiles are detected and defensively countered with constructive missile shots from ships in real time. In live training, fleet and contracted aircraft act as opposition force aircraft regardless of their operating characteristics compared to the actual threat. Within LVC, live opposition force aircraft are enhanced with accurate threat radar emissions and launch constructive antiship cruise missiles to be detected by ship electronic warfare and radar systems.3

LVC training uses tactical training range infrastructure, the Navy Continuous Training Environment, and Joint Semiautomated Forces modeling and simulation and requires ships to align their combat systems in training mode at sea. Ship crews follow their combat system operating sequencing systems (CSOSSs) to correctly align the training systems, C4I, and combat systems to process both live and synthetic injects. The CSOSS procedures are adapted from the ship’s “normal” method of using training mode at sea, including various deviations and relaxations. Strike group training in this LVC environment has been tested and approved by Naval Sea Systems Command and Naval Air Systems Command. Both commands are required to ensure LVC can be conducted safely without accidental weapon release or interference with safe navigation or flight operations.

Many conditions or situations affect the ability to deliver LVC training. While not necessarily unsafe, improperly aligning the ship’s combat system can result in instability, causing the training and/or combat systems to “fall out of training mode.” This disrupts the scenario and prevents full crew participation until the situation is corrected. Synthetic injects are delivered via satellite, so any disruption in data service will prohibit the ship from receiving them.

Furthermore, the Battle Force Team Trainer system does not interface well with all ship information technology baselines. For example, Aegis weapon systems can simultaneously process live and constructive injects, but the Ship’s Self-Defense System (SSDS) on aircraft carriers and amphibious ships was specifically designed to prevent this occurrence. The East and West Coast training carrier strike groups must carefully account for Aegis and SSDS training system limitations in developing LVC scenarios. Exercise design must also account for littoral combat ships and Zumwalt-class destroyers, which were delivered without onboard training systems or systems that do not support distributed training. Separately, live allied and coalition platforms are currently not compatible with virtual and constructive injects and can only share a Link-16 picture.

Perhaps most critical with LVC training is the inability of aircraft to receive direct virtual or constructive stimulation. Aircraft can detect only the live environment. Using a networked solution of ship and aircraft tracking pods combined with Joint Semiautomated Forces modeling and scenarios to blend the scenario presentation partially alleviates this shortfall. An opposing force ship or aircraft with a tracking pod can be “ghosted” or “guised” (synthetically overlayed) with constructive components that can be detected by ships in training mode.

Despite these limitations, LVC can greatly enhance the live presentation, as well as expand the battlespace the training audience must consider in planning and decision-making. A multiaxis antiship cruise missile attack with the combination of fully constructive and ghosted live forces is easily accomplished in an LVC environment. No longer must the known physical range or operating area limitations (e.g., Federal Aviation Administration restrictions, national airspace, etc.) force the training audience to narrow the scope of the scenario.

Future of LVC

While adapting existing technologies can expand LVC training, much more must be done to meet the CNO and Marine Corps Commandant’s direction and intent. LVC training has been embraced by the training community as well as by exercise designers up to the component commander level, but LVC training faces technical limitations without additional investment.

Expeditionary Warfare Training Group Pacific has conducted several LVC events, but increased integration with Marine Corps systems is an imperative. Naval aviation envisions LVC training will be at its full capability in 2035 when live units are able to “detect, track, classify, and engage virtual/constructive entities—and vice versa—with both kinetic and non-kinetic effects.”4 Ultimately, Tactical Combat Training System Increment (TCTS) II will fulfill this requirement using a secure waveform.

Air Test and Evaluation Squadron 23 recently flew TCTS II on fleet F/A-18s, but full implementation across all type/model/series aircraft remains several years away.5 To meet that goal across all platforms, Navy resource sponsors must consistently keep training systems and LVC enablers above the budget funding cut-line. Every tactically relevant system must be integrated into platform training systems and must enable multilevel security, multidomain functionality, and fully informed training. The high-end fight will not wait for training to catch up.

1. U.S. Naval Air Enterprise, Navy Aviation Vision 2030–2035 (October 2021).

2. Thomas G. Mahnken and Regan Copple, “Bring U.S. Operational Training and Experimentation into the 21st Century,” Defense News, 23 November 2020.

3. EWA Government Systems, “Battle Force Electronic Warfare Trainer (BEWT),” www.ewa.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/BEWT.pdf.

4. U.S. Naval Air Enterprise, Navy Aviation Vision 2030–2035.

5. LCDR Colin Locke, USN, “Integrating the Live and Virtual Environments for Development and Training,” Navy.mil, 3 October 2022.