The Sea Services have an extensive if long-dormant history with seaplanes. The first aircraft the U.S. Navy ever purchased was an amphibious seaplane, in 1911. The Marine Corps bought its first in 1913.1 Small single-engine float planes and large multi-engine seaplanes were widely used in World Wars I and II for fleet scouting, antisubmarine warfare (ASW), naval gunfire spotting, deploying mines, rescuing downed airmen, and attacking enemy ships. The Cold War saw seaplanes gradually replaced by land-based patrol aircraft that were faster, more affordable to operate, and sufficiently flexible—given a network of air bases. The Navy retired its last seaplane in 1967.

Now, as during World War II, the United States is focused on competition with an expansive, aggressive, high-technology naval power in the Pacific. National boundaries, governments, and alliances have changed in this vital region. Geography has not. Distances in the Pacific remain immense, while the handful of regional air bases on which the joint force depends for power projection and sustainment are obvious targets.

Seaplanes have gained attention as solutions to the tyranny of distance, yet attention has focused on large, manned seaplanes for logistics and support tasks.2 But an emerging family of small, uncrewed seaplanes could be used in riskier, tactical roles. Such vehicles are being developed to fill commercial maritime roles that require endurance, mobility, and flexibility. These attributes align well with requirements for expeditionary advanced base operations (EABO), which put Marine Corps units at austere bases inside the adversary’s weapon engagement zone (WEZ) to support a broader naval campaign.

The Marine Corps should build uncrewed seaplane squadrons to support Marine littoral regiments (MLRs). Broken into sea-mobile detachments, the squadrons would contribute across the spectrum of competition: providing maritime surveillance to joint and allied forces while campaigning, holding contact on adversary naval forces in the deterrence phase, and supporting multiple kill chains in conflict. Thanks to small size and low costs, their ability to operate from thousands of miles of coastline would provide a flexible, mobile, persistent, and cost-effective platform for the stand-in force.

Standing In to Stand To

Since 2019, the Marine Corps has redefined itself as the stand-in force, persisting inside an adversary’s WEZ and “operat[ing] with allies and partners, establishing the leading edge of a maritime defense in depth.”3

As the land-based eyes and ears of a naval campaign, stand-in forces provide persistent intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, and targeting (ISRT) and counter-ISRT to the fleet. EABO is driving major changes in how the Marine Corps is manned, trained, and equipped. The second edition of the Tentative Manual for Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (EABO) has identified six core attributes of stand-in forces. Uncrewed seaplanes offer benefits within each, but three stand out.4

Persistence. “Moving with a high degree of flexibility within areas of key maritime terrain, presenting a light posture, sustaining themselves in an austere setting, and protecting themselves from detection and targeting. EABO diminish the reliance on fixed bases and easily targetable infrastructure.”

Low Signatures. “Carefully manag[ing] signatures at all times, especially while conducting localized movement and maneuver.”

Cost-effectiveness. “Small, numerous, dispersed, relatively simple to maintain, and difficult to target, thus inverting an adversary’s cost-benefit calculation when deciding whether to engage and upsetting the cost-imposition strategy.”5

Uncrewed aerial systems (UASs) in general must necessarily play a large role as part of stand-in forces’ aviation capabilities.6 Unfortunately, the majority of Department of Defense UASs are expensive ($28 million for an MQ-9 Reaper, for example), not persistent in the face of resistance, and unable to stand in within contested environments.7

Help Wanted: Risk-Worthy Maritime Scouts

Platforms supporting stand-in forces must be risk-worthy and cost-effective. Pursuing capability and survivability for each individual platform is the wrong idea. Instead, the systems should comprise inexpensive units that distribute capability over multiple nodes. In this way, the system would remain capable despite the loss of some individual platforms. Such an approach could change an adversary’s cost-benefit calculation, calling into question the value of launching an expensive fighter aircraft or expending a multimillion-dollar missile to shoot down a cheap and easily replaced drone.

Commercially available uncrewed seaplanes are a niche sector of the multibillion-dollar UAS market. Variations include uncrewed pontoon-equipped floatplanes, flying boats that use their hulls for buoyancy, and amphibians with wheels and floats that permit operations from land and sea.

Current commercial uses for uncrewed seaplanes include: at-sea cargo delivery; ocean surveillance; maritime security; maritime search and rescue; agricultural support; oil and gas infrastructure monitoring; and fish and aquatic life tracking—ISRT, for all practical purposes.8 The commercial UAS market rewards low acquisition and operating costs, so adapting commercial models would benefit the stand-in force. Japan’s Space Entertainment Laboratory Co. offers the Hamadori 3000, for example, for around $225,000 per aircraft.9

The aircraft typically weigh 150 to 450 pounds each—squarely inside the Department of Defense’s midtier UAS Group 3 category.10 They can be launched or recovered in moderately high sea states and remain aloft for multiple hours. Speed is not vital, with most cruising at less than 100 knots. Endurance is the key consideration, varying from as little as 2 hours to as many as 15. Thanks to their small size, many seaplane uncrewed aerial vehicles (UAVs) have modest fuel requirements, improving costs and reducing logistical burdens. The ongoing development of hydrogen fuel cells and battery technologies could further improve both.

Mobility and Persistence

Fixed air bases in the Pacific are in short supply and obvious targets. The Center for Strategic and International Studies’ recent wargames examining a potential conflict in the western Pacific indicated that missile attacks on U.S. and allied air bases could destroy hundreds of aircraft on the ground and leave many airfields devastated and at least temporarily unusable.11 A seaplane UAS would be much less susceptible to this threat, because its ability to operate from anywhere in the littorals would afford the mobility, flexibility, and resilience land-based manned and uncrewed aircraft lack.

Nowhere is this advantage more apparent than in the strategically vital first island chain, a 3,000-mile-long arc extending from the Kuril Islands at its northernmost, southwest through Japan, Taiwan, the Philippines, and into the South China Sea.12

The Philippines, which sits in the middle of the first island chain, adjacent to China’s vital sea lines of communication, is at the frontline of the competition. With 7,600 islands and a land mass similar to the state of Arizona’s, the archipelago stretches 800 miles from north to south and has 22,000 miles of coastline. But it has fewer than 50 paved airfields 5,000 feet or longer—the length required for many large, manned aircraft and big-wing UAVs. And these possess a total area of around 50 square miles, offering a fairly simple target list to an adversary who wishes to disrupt land-based ISRT operations.13 It is worth noting that, on 8 December 1941, Imperial Japanese attacks on the Philippines destroyed nearly half the U.S. Army Air Forces land-based bombers and a sizable proportion of its fighters on the ground, while dispersed Navy seaplanes suffered just 5 percent losses.14

Distributed seaplane ISRT operations, on the other hand, would require China to maintain constant surveillance across 40,000 square miles of coasts, beaches, rivers, and lakes. And then, Chinese forces would face the challenge of quickly tracking, targeting, and engaging any targets they identified.

The Uncrewed Seaplane Squadron

A Marine uncrewed seaplane squadron (VMU[S]) would be equipped with approximately 18 small seaplane UAVs, organized into three detachments of six UAVs, each with one or more portable mission control systems. Each detachment would comprise perhaps eight to ten Marines with the skills to support, operate, and maintain their assigned vehicles and systems. The detachment would travel in small craft similar to the Navy’s former 53-foot riverine command boats. These would function as miniature seaplane tenders, moving frequently throughout the region.

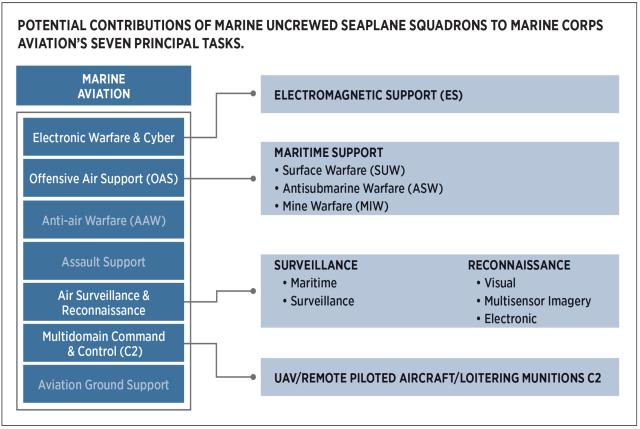

The Marine Corps has identified seven principal tasks for its aviation units: electronic and cyber warfare; offensive air support; air surveillance and reconnaissance; multidomain command and control; antiair warfare; assault support; and aviation ground support. VMU(S) detachments would be capable of swapping mission payloads to support the first four.

Campaigning: Show the Flag

It is often said you cannot surge trust, and a principal tenet of EABO is to build it ahead of time through early and constant engagement with local allies and partners to counter threat networks, preserve access, and shape the theater for future operations.

A VMU(S)’ ability to persist within contested littorals while maintaining a small signature would allow it to be present before the onset of hostilities, supporting a forward-deployed MLR and contributing across the phases of competition. In the campaigning phase, a VMU(S) equipped with maritime search radar and/or electro-optical and infrared (EO/IR) sensors would provide allies with critical maritime domain awareness capabilities.16 Missions supported would include training with host nation militaries and coast guards, counterpiracy, counterinsurgency, counterterrorism, and general maritime security. The campaigning phase would enable a VMU(S) to exercise its full set of expeditionary capabilities.

Critically, the availability of “low-end” seaplane UASs could free larger, more capable, and expensive manned and uncrewed platforms for higher-end deterrence-related tasks—for example, freeing a costly long-range P-8A Poseidon from a low-end maritime surveillance mission better suited to a UAV and allowing the P-8A instead to detect, track, and engage adversary submarines.

Deterrence: Eyes on Target

The Concept for Stand-In Forces says that “for deterrence to succeed, it must shape the thinking of a potential aggressor.”17 It is not only necessary that adversaries be observed; they must also know they are being observed and that such observation poses the potential of an attack or other adverse consequences. VMU(S) detachments would serve this role by providing a mobile, high-endurance, and overt surveillance capability over potential adversary ships the moment they enter the littoral battlespace, especially in maritime choke points. The seaplane UAS would be equipped with lightweight sensors capable of tracking and identifying targets such as EO/IR or electronic signals measurement.

In a maritime-fires kill chain, a seaplane UAV would complement the capabilities of larger medium- and high-altitude, long-endurance UAVs (such as MQ-9 Reapers and MQ-4 Tritons). These UAVs would be used to find a target and then stand off while a more risk-worthy vehicle would be used to fix and track the target while collecting vital electronic warfare intelligence (and holding contact until a firing order is given when conflict arrives). A VMU(S)’s swarm of 18 seaplane UAVs for ISRT would preserve the costly and vulnerable high-end UAVs for the wide-area search tasks for which they are better suited.

When deterrence-by-observation is not a goal, an uncrewed seaplane could also take advantage of the maritime environment to avoid detection and targeting by adversary forces. Its small size and ability to operate at mere feet over the water, or even temporarily on the water, could reduce the distance at which adversary surface-based sensors could detect it, thanks to sea clutter, reflection, and water spray, each of which can disrupt sensors.

Conflict: Use It and (Probably) Lose It

Should deterrence escalate to conflict, VMU(S)s already present in theater and in numbers would be distinctly useful.

To ensure that seaplane UAVs are unable to maintain tracks on its ships, an adversary surface force would need to detail a larger number of higher capability platforms for screening operations. Or, equipped with appropriate communication packages, seaplane UAVs could maintain vital networks among targeting platforms, tactical commanders, and firing units (such as an MLR Naval Strike Missile battery). In all cases, many seaplane UAVs would likely be shot down—but their low cost would allow for sufficient inventory to permit quick replacement.

Persistent and ubiquitous seaplane UAV presence inside the adversary’s WEZ suggests additional potential roles. For example, Marine Corps leaders have expressed interest in supporting the antisubmarine warfare (ASW) mission.18 Seaplane UAVs equipped with magnetic anomaly detectors or other lightweight sensors could search for adversary submarines, especially at maritime choke points. A VMU(S) detachment could maintain a nearly continuous barrier with a high revisit rate, denying undetected passage to transiting submarines. Pairing an uncrewed seaplane with a torpedo-equipped helicopter could complete the ASW kill chain.

Think Small to Win Big in the Littorals

The Department of Defense appears to be betting that small and cheap uncrewed systems will have a major role to play in future conflict. Former Chief of Naval Research Rear Admiral Lorin Selby observed in 2021 that “the small, the agile, and the many have the strong potential to define the future in a world where the large and the complex are either too expensive to generate in mass, or potentially too vulnerable to put at risk.”19 Deputy Secretary of Defense Kathleen Hicks established the Replicator Initiative to rapidly deliver uncrewed systems that are “small, smart, cheap, and many.”20 Operations in Ukraine have provided real-world evidence of the value of small, cheap, and numerous uncrewed systems.

The timing is right for the Marine Corps to explore this disruptive concept more fully. The 2023 Annual Update to Force Design 2030 directs that by summer 2024, the service’s headquarters will need to “identify ways to increase and maintain a persistent Marine aviation presence across the physical expanses of littoral geography and inside an adversary’s WEZ.”21 Integrating a commercially available uncrewed seaplane system into its cycle of wargaming, analysis, experimentation, and exercises would show whether this new application of the original naval aviation platform could contribute meaningfully to the Marine Corps’ ability to remain mobile, survivable, and lethal in the contested littorals.

1. John Elliot, “Marine Corps Aircraft 1913–2000,” History and Museums Division, Headquarters U.S. Marine Corps, 2002.

2. Christopher D. Booth, “Overcome the Tyranny of Distance,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 146, no. 12 (December 2020).

3. A Concept for Stand-in Forces (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, December 2021), 6.

4. Tentative Manual for Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations 2nd edition (Washington DC: Headquarters U.S. Marine Corps, May 2023), 1-2.

5. Tentative Manual, 1-4.

6. A Concept for Stand-In Forces, 22.

7. John R. Hoehn and Paul K. Kerr, Unmanned Aircraft Systems: Current and Potential Programs, Congressional Research Service, crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R47067/5, 28 July 2022.

8. “What Are Unmanned Seaplanes?” The Corona Wire blog, undated, www.thecoronawire.com/what-unmanned-seaplanes-floating-drones-explained.

9. Chris Loew, “Japanese Company Trials Seaplane Drone in Fish Spotting,” Seafood Source, 10 August 2022.

10. Group 3 vehicles weigh less than 1,320 pounds, operate below 18,000 feet, and fly at speeds of less than 250 knots.

11. Mark Cancian, Matthew Cancian, and Eric Heginbotham, The First Battle of the Next War: Wargaming a Chinese Invasion of Taiwan (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, January 2023).

12. See James Holmes, “Defend the First Island Chain,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 139, no. 4 (April 2014).

13. Philippines Airports with Paved Runways, www.indexmundi.com/philippines/airports_with_paved_runways.html.

14. David Allman, “Bring Back the Seaplane,” War on the Rocks, 1 July 2020.

15.Table generated from multiple sources including the Space Entertainment Laboratory website and the now-defunct Warrior Aero Limited website.

16. Tentative Manual, 1-5.

17. A Concept for Stand-In Forces, 5.

18. Gen David H. Berger, USMC, “Marines Will Help Fight Submarines,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 146, no. 11(November 2020).

19. Warren Duffie Jr., “‘Our Time to Innovate is Now’: Chief of Naval Research Reimagines Naval Power for 21st Century,” Office of Naval Research, 8 December 2021.

20. Jim Garamone, “Hicks Discusses Replicator Initiative,” DoD News, 7 September 2023.

21. Force Design 2030 Annual Update (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, June 2023).