All warfare is based on deception. Hence, when we are able to attack, we must seem unable . . . when we are near, we must make the enemy believe we are far.

—Sun Tzu, The Art of War

Marines in the Infantry Officers’ Course memorize what some call the Rules of the Infantryman. While the rules have evolved over time, the third and final rule has remained unchanged: “Deception in all that you do.” Unfortunately, this mantra receives little further emphasis. It is largely forgotten in the Marine Corps’ training and education continuum.

Deception, critical to both surprising the enemy and ensuring force protection, is an art in need of attention. For the Marine air-ground task force (MAGTF) to create and maintain a competitive advantage in the future operating environment, the service must inculcate a culture of deception across the force.

The What and Why of Deception

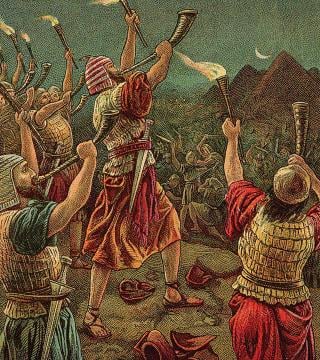

Deception in war is as old as conflict itself. In the Western tradition, the Bible chronicles Gideon’s plan to deceive the Midianites in 11th century BC. As he approached the outskirts of the enemy encampment, he ordered his outnumbered men to surround the enemy camp and “when I . . . blow [my] horn, then you . . . blow your horns . . . and shout, ‘For the Lord and for Gideon!’”1 Believing they were surrounded by a larger force, the Midianites fled. In the Eastern tradition, military deception is embodied by Sun Tzu’s principles and the ancient tactical adages contained in the 36 Stratagems.2

Today, the Marine Corps sees deception as a function of information operations (IO), defining it as “actions executed to deliberately mislead adversary . . . decision-makers,” causing them to “take specific actions (or inactions) that will contribute to the accomplishment of the friendly mission.”3 Joint doctrine calls this military deception (MilDec), which is “intended to deter hostile actions, increase the success of friendly defensive actions, or to improve the success of any potential friendly offensive action.”4 Put simply, deception aims to confuse the enemy, and, in this state of confusion, render him vulnerable to surprise.

There are many examples of the realities faced in contemporary conflicts and the resultant need for deception. Small-unmanned aerial systems flood the battlefield. Tactical satellites permeate low earth orbit, enabling persistent C4ISR. The proliferation of precision-guided munitions has upended decades of doctrine and assumptions regarding the efficacy of conventional offensive operations. Enemies have never had a greater ability to seek and strike centers of gravity and critical vulnerabilities.

In the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war, Azerbaijani forces not only employed loitering munitions to great effect, but also reportedly weaponized antiquated biplanes, using them to draw out or destroy Armenian air defenses in unmanned kamikaze attacks.5 In the Russia-Ukraine war, loitering munitions, commercially available drones, and a wide range of precision-guided munitions are being used. Modern battlefields show the lethal realities of 21st-century war. As the Marine Corps Operating Concept eloquently posits: “To be detected is to be targeted is to be killed.”6

But by deceiving the enemy as to friendly force locations and disposition, leaders can reduce the chances of detection and bolster survivability. By deceiving the enemy as to friendly force intentions, they can ensure operational surprise. Such deception can take many forms. The deceiver’s toolkit is diverse and brimming with historical examples.

The Marine Corps and Deception

One example of successful MilDec occurred during General Douglas MacArthur’s Operation Chromite. Mac-Arthur was inspired by his belief that North Korean leaders were convinced an amphibious assault at Inchon was impossible. His staff crafted an elaborate deception operation, masking the selection of Inchon as the landing site.

MacArthur drew North Korean attention away from Inchon, south to Kunsan, where U.S. forces raided enemy positions, conducted strikes on key infrastructure and military installations, and held false briefings that could be easily leaked.7 Taking the North Koreans by surprise, Chromite broke the back of the Communist forces. At a time in which questions about the feasibility of amphibious invasions were rampant, deception was critical to the success of the assault.

Unfortunately, despite the Marine Corps’ historical experience with deception, there is little record of attempts to institutionalize deception in service doctrine or force structure until the 2009 publication of MarAdmin 0266/09.8 This document created the Marine Corps Information Operations Center and formalized the 0510 Information Operations Staff Officer military occupational specialty for captains and above. For the Marine Corps, deception resides within the realm of information operations (IO).

IO planners are to be jacks-of-all-trades, championing a litany of capabilities including electronic warfare, operations security, psychological operations, information assurance, public affairs, civil-military operations, and—finally—military deception.9 Yet, with so many responsibilities, the immaturity of the career field, limited experience, and the lack of understanding of IO utility and purpose across the force, IO planners easily can be and often are relegated to minor, ancillary efforts. Serious deception planning goes with them.

EABO: The Future of Deception

The lack of serious attention to MilDec is especially concerning given the Marine Corps’ and MAGTF’s trajectory. Deception is fundamental to the underpinnings of expeditionary advanced base operations and associated stand-in forces. Both the Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (EABO) Handbook and A Concept for Stand-In Forces stress deception as critical to survive and win in the next fight.

Envisioning a future of expeditionary advanced bases facilitating sea denial and enabling friendly force access against a peer adversary, the EABO Handbook posits that such bases must “use passive defenses and rely upon mobility, deception, and concealment to compound the adversary targeting problem.” Similarly, it notes that deception is required to “win the hider/finder competition” inherent in peer conflict.10

A Concept for Stand-In Forces pays even more attention to deception. Stand-in forces (SIF), defined as “small but lethal, low signature, mobile, relatively simple to maintain and sustain forces designed to operate across the competition continuum within a contested area,” must be survivable.11 Because these forces will operate in contested areas, “understanding deception is critical.” Without decoys, masking, and signature management, SIF cannot survive to enable EABO and associated maritime campaigns.12 More attention must be given to conceptualizing, training, and inculcating deceptive mindsets to ensure maritime and littoral operational success as envisioned by EABO and SIF.

What To Do

There are three primary avenues to explore:

Teach and Train, Early and Often. Writing about British Field Marshall Edmund Allenby during World War I, T. E. Lawrence observed the serious integration of deception in operational planning in the Third Battle of Gaza.13 He celebrated what he saw as the culmination of decades of training, education, and experience. Developing the knowledge, skills, and ability to incorporate deception in a combined arms model today will require similar deliberate training and education. Outside the limited experience within the IO community and basic exposure at entry-level infantry schoolhouses, such training is absent in the Marine Corps. Deception is not prioritized, despite its centrality to surviving and winning on the modern battlefield.

To begin to address this gap, Marines could be taught a set of “deception principles.” For example, Magruder’s Principle holds that “it is generally easier to induce the deception target to maintain a preexisting belief than to deceive the deception target for the purpose of changing that belief.” It is easy to see the applicability of such principles to facilitating and planning deception operations. Additional maxims can facilitate deception on the battlefield—for example, Jones’ Dilemma and “Multiple Forms of Surprise.”15 If these are unfamiliar, that is the point. None are taught outside the IO curriculum. Including specific, deception-focused educational objectives throughout professional military education should be the first step to inculcating deception in the collective military mindset.

Find and Free the Deceivers. After studying more than a hundred examples of military deception, denial and deception authority Barton Whaley observed that the most effective deception planners “usually—perhaps always—bring . . . a talent for deception based on prior understandings of deception, however vague.”16 Finding these individuals and sharing their ideas is imperative for leaders at every level. They could be:

• A squad leader who creates innovative dummy positions to facilitate an ambush

• A driver who discovers a unique way to mask his vehicle’s heat signature

• A logistician who creatively prepositions hidden caches to surreptitiously resupply troops in the field

Just as important to finding these key deceivers, however, is encouraging the creative process, accepting risk, and allowing experimentation and failure. Leaders must incentivize and encourage this if they wish to develop a culture of military deception.

Take a New Look at Deception Planning. MAGTF deception planning formally rests within the purview of IO planners and is operationally detailed in A Concept for Information Operations. Separating deception into its own concept would highlight its importance. While IO and force protection are addressed separately at the MAGTF level, a “Concept for Deception” should be considered and institutionalized as a separate entity to habituate Marines to its importance.

At the MAGTF level, the operations officer should have the best insight into the commander’s intent and ability to craft a suitable deception plan. At the battalion and lower levels, addressing a “Concept for Deception” would provide a venue to discuss a wide range of maneuver, tactics, techniques, and procedures that aid in deceiving the enemy. Building a lasting planning culture takes time and repetition. Developing a MilDec plan regardless of unit size will aid in formalizing a thorough approach to deception planning.

Survive and Succeed

While creating a deception culture will enable the MAGTF to survive and succeed, some may find the concept unfamiliar and uncomfortable. But deception has been practiced throughout Marine Corps history—from General Harry Schmidt’s feint that diverted the Japanese during the battle of Tinian, to the U.S. Army 23rd Headquarters Special Troops’ Ghost Army of inflatable decoys and sound effects that deceived the Germans about the D-Day landing site.17

Unlike the battlefields of World War II, however, the democratization and proliferation of new technologies have made the modern battlefield increasingly transparent and targetable. Deception is essential to the MAGTF’s survival and ability to obtain a decisive advantage over its foes. Only by intentionally fostering a culture of deception through training, education, and deliberate deception planning can the Marine Corps ensure deception becomes and remains part of all it does.

1. Judges 7:18, in John K. Riches, The Bible: A Very Short Introduction, 2nd ed. (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2023).

2. “Make a sound in the east, then strike in the west.” Peter Taylor, The Thirty-six Stratagems (Oxford, UK: Infinite Ideas Limited, 2013), ch. 6.

3. U.S. Marine Corps, Marine Corps Warfighting Publication (MCWP) 3-40.4: Marine Air-Ground Task Force Information Operations (Washington, DC: Headquarters U.S. Marine Corps, 2013), glossary-5.

4. Department of Defense, Joint Publication 3-13.4: Military Deception (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 2012), vii.

5. Shaan Shaikh and Wes Rumbaugh, “The Air and Missile War in Nagorno-Karabakh: Lessons for the Future,” CSIS, 8 December 2020.

6. U.S. Marine Corps, Marine Corps Operating Concept: How an Expeditionary Force Operates in the 21st Century (Washington, DC: Headquarters U.S. Marine Corps, September 2016), 6.

7. Curtis A. Utz, Assault from the Sea: The Amphibious Landing at Inchon, no. 2 in The U.S. Navy in the Modern World Series (Washington, DC: Naval History and Heritage Command, 2020).

8. MarAdmin 0266/09: “Establishment of the Marine Corps Information Operations Center (MCIOC),” 22 April 2009.

9. MCWP 3-40.4, Marine Air-Ground Task Force Information Operations, 14-33.

10. Art Corbett, Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (EABO) Handbook, version 1.1 (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps Warfighting Lab, Concepts & Plans Division, 1 June 2018), 27.

11. Gen David H. Berger, USMC, A Concept for Stand-in Forces (Washington, DC: Headquarters U.S. Marine Corps, December 2021).

12. Rémy Hémez, “To Survive, Deceive: Decoys in Land Warfare,” War on the Rocks, 22 April 2021.

13. T. E. Lawrence, Seven Pillars of Wisdom (1926), 615. Allenby sent out false radio messages and planted fake military plans for a British attack on Gaza and instead attacked at Beersheba.

14. Department of the Army, Field Manual (FM) 3-13.4: Army Support to Military Deception (Washington, DC: Headquarters, Department of the Army, February 2019), 16.

15. According to FM 3-13.4, Jones’ Dilemma holds that “deception generally becomes more difficult as the number of conduits available to the deception target to confirm the real situation increases. However, the greater the number of conduits that are deceptively manipulated, the greater the chance the target will believe the deception”(1-9). Again from FM 3-13.4, Multiple Forms of Surprise posits that “the more forms of surprise built into the deception plan, the more likely it will overwhelm the target. These forms of surprise include size, activity, location, unit, time, equipment, intent, and style” (1-9).

16. Barton Whaley, Practice to Deceive: Learning Curves of Military Deception Planners (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2016), xiv.

17. As part of Operation Forager, the combined amphibious force conducted an amphibious demonstration and naval shore bombardment on the southwestern side of Tinian, opposite where the actual landing would occur. The deception worked and the actual landing force took few casualties. See Samuel J. Cox, “H-033-3: Operation Forager, Part 2: The Invasion of Tinian,” Naval History and Heritage Command, July 2019.