Editor’s Note: Since this article was published, the PLAN conducted an additional training cruise. An update on that deployment has been appended to the end of this article.

The details of China’s recent aircraft carrier operations provide some necessary perspective on the burgeoning capabilities of the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN). Technical capabilities are not sufficient; how and where the PLAN operates must be considered. Beyond simple math—ship tonnage, salvo rates, and weapon ranges—what matters in a comprehensive net assessment of competing military forces are operational capabilities and geometry. China’s demonstrated intent to operate at long ranges from the Chinese coast signals how the PLAN may fundamentally change threat geometry in the Pacific as its operational capabilities improve.

PLAN Air Force (PLANAF) J-15 Flanker-X2 fighters first landed on board the Chinese aircraft carrier Liaoning on 25 November 2012. I was an assistant U.S. naval attaché to Beijing at the time. At a diplomatic reception, I congratulated my PLAN colleagues on joining the elite group of aircraft carrier–capable navies. They humbly downplayed my compliments. The Chinese officers understood that U.S. Navy achievements in carrier aviation had come at a high cost in aircraft and lives. The PLAN has proceeded cautiously in developing its carrier program since then. Ten years on, while a few J-15s have been reported lost in training accidents, the PLAN apparently has yet to suffer a major flight-deck incident.

The PLAN has since claimed the title of the world’s largest navy. Chinese Communist Party Chairman and President Xi Jinping has pressed his military to increase the realism of training, ostensibly to prepare to “fight and win wars.” Each month, the media seems to reveal a new Chinese missile or report the launch of yet another combatant. In December 2019, the PLAN commissioned its second aircraft carrier, the Shandong. The Type 002 Shandong, with its ski-jump bow to assist aircraft takeoff, is a domestically produced copy of the Soviet-era Kuznetsov-class carrier that was refitted to create the Type 001 Liaoning. In June 2022, China launched its Type 003 aircraft carrier, Fujian, a flat-deck carrier that reportedly employs electromagnetic catapults in lieu of the ski-jump design. However, for all this apparent progress in naval force structure, the PLAN is still growing its operational capabilities to use new technologies to full effect.

Chinese military analysts have heralded recent Liaoning strike group deployments to the western Pacific as featuring “intensive aircraft sorties” and evidence of a “high combat capability.”1 Even the relatively new Shandong has reportedly conducted its first “realistic combat-oriented exercises” in the South China Sea.2 However, a close examination of these recent exercises shows the PLAN continues to conduct carrier operations with an abundance of caution. These operations reveal the changing geometry of naval operating areas in East Asia and how they could generate advantages and risks.

Flight Ops Geometry

The Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF) provides reliable public reporting on how and where the PLA has been operating in the East China and Philippine Seas.3 Based on this, the PLAN might have achieved another naval aviation milestone: blue-water aircraft carrier operations. “Blue-water ops” is shorthand for conducting carrier fixed-wing flight operations outside the unrefueled range of a divert airfield, a place to land if an aircraft cannot return to the ship. Any number of maintenance issues or damage to either the aircraft or the carrier might preclude a safe recovery. Conducting true blue-water ops is a high-risk endeavor. The only outcomes are either a 100 percent onboard recovery rate or losing an aircraft.

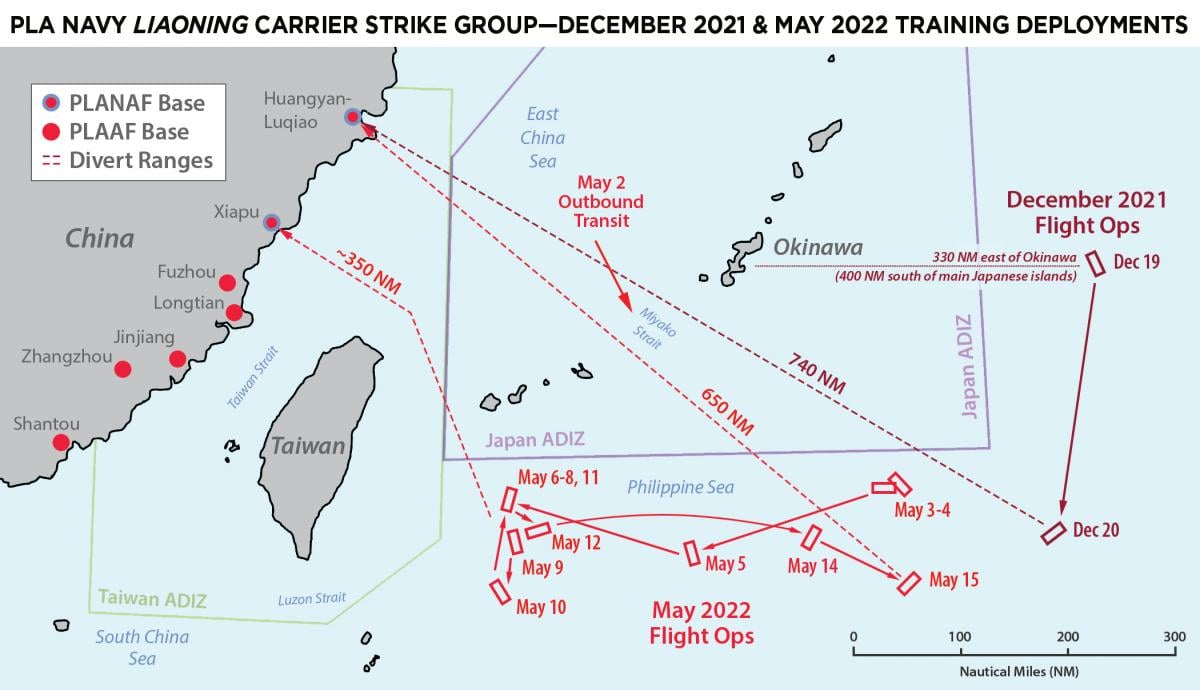

According to the JMSDF, during a December 2021 training deployment to the Philippine Sea, the Liaoning conducted fixed-wing flight operations more than 700 nautical miles (nm) from the Chinese mainland on at least two occasions. In May 2022, on a more substantial three-week training deployment to the Philippine Sea, the Liaoning conducted about half its flight operations between 500 and 600 nm from China. The other flying days occurred in an area east of Taiwan, still a respectable 300–400 nm from a divert airfield.

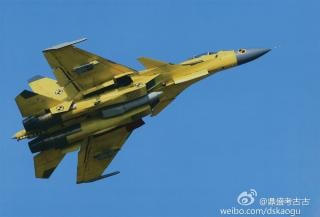

There is some question about how risky PLAN blue-water ops were, or if they were “blue-water” at all. China’s J-15, a reverse-engineered copy of Russia’s Su-33, is marginally larger than the venerable U.S. F/A-18E/F Super Hornet—10 percent longer and wider, with 40 percent more wing area. The J-15’s 20,000 pounds of internal fuel stores purportedly give the J-15 an impressive high-altitude transit range of more than 1,600 nm.4 Assuming low-intensity flight operations relatively close to the carrier, a J-15 theoretically would be able to reach the Chinese mainland from 700 nm if it maintained a 50 percent fuel reserve. J-15s also have demonstrated limited proficiency in air-to-air refueling, using the Russian UPAZ-1A fuel pod for fighter-to-fighter “buddy tanking.”5 The large, center-mounted tanks were not seen in photos or videos of Liaoning flight operations, nor were there any reports of PLA Air Force (PLAAF) H-6 or Y-20 air-to-air tankers from the mainland supporting carrier flight operations.

The PLAN likely pursued cautious, low-intensity flight operations to maximize aircraft fuel reserves for a divert and reduce overall risk to carrier operations. JMSDF photos and PLA video of the deployment showed J-15s either flew “clean,” without any drag-inducing external stores or with a few relatively light air-to-air missiles. No large payloads involving air-to-surface weapons, drop tanks, or pods were noted. Japanese officials reported the Liaoning conducted more than 300 aircraft sorties during the May 2022 deployment.6 Over the 12 days of reported flight ops, that averages to fewer than 20 fighter sorties per day, combined with dozens of helicopter flights throughout the deployment. Chinese military commentators declared this to be a “decent number” of sorties for training.7 For some perspective on those numbers, the U.S. aircraft carrier USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78) recently set a record for completing 170 sorties in eight and a half hours of training.8

Threat Axis Geometry

The map of the Liaoning’s movements in the Philippine Sea shows the Chinese carrier purposefully conducted flight operations just outside of Japan and Taiwan’s air defense identification zones (ADIZ). An ADIZ is not territorial airspace but represents an area in which a nation has declared it will identify and intercept unidentified or threatening aircraft. Chinese carrier operations east and south of these zones stress Japan and Taiwan’s air defenses. For example, during the recent Liaoning deployments, Japan Air Self-Defense Force (JASDF) fighters based on Okinawa would have had to fly intercepts up to 250 nm to the southeast corner of their ADIZ while still maintaining vigilance for threats from mainland China. A PLA video of the Liaoning’s December 2021 deployment featured images of a JASDF F-15 fighter viewed from the cockpit of a PLAN J-15.9 Chinese and Japanese fighters operating so close to one another, especially in the Philippine Sea, is a rare and somewhat concerning development. The range and geometry of the Liaoning’s flight operations help explain why Japan sent one of its own carriers to shadow the PLAN deployment in May 2022.10

Scores of PLA land-based aircraft that entered Taiwan’s ADIZ in May 2022 were likely designed to test how Taiwan responded when faced with threats approaching from both east and west. On 6 May, as the Liaoning moved into position east of Taiwan, a dozen land-based PLA fighter-bombers entered Taiwan’s southwest ADIZ.11 At the end of the deployment, on 18 May, two H-6J bombers swept through the Philippine Sea, likely simulating the clearance of exercise “enemy” forces before the Liaoning strike group transited back to the East China Sea.12

The support the Chinese carrier received from land-based PLA airborne radar and maritime patrol aircraft highlights one of the most critical geometries for modern naval operations: elevation and the advantages of looking down on the battlespace. The curve of the Earth limits a ship’s ability to detect low-altitude or surface targets beyond the horizon. Large, heavy radar-surveillance aircraft such as the U.S. Navy’s E-2D Hawkeye are unable to launch from Chinese carrier ski jumps. The Liaoning operates Z-18 helicopters equipped with a 360-degree airborne radar. Z-18s are unable to operate for long periods or at high altitudes for increased radar range. These critical limits on battlespace awareness will change in the coming years as the catapults on China’s Type 003 Fujian carrier will allow it to launch the recently revealed KJ-600 airborne early warning and control aircraft, which bears a striking resemblance to the E-2D.13

Missile-Defense Geometry

Aircraft carriers have arguably been the centerpiece of U.S. naval strategy since World War II. The PLAN is certainly drawn to the international prestige of operating aircraft carriers. However, the centerpiece of PLAN strategy, especially over the next decade, will likely continue to be the strike capabilities of its surface combatants and submarines.

Seven PLAN ships accompanied the Liaoning on its May 2022 deployment to the Philippine Sea: one Type 055 Renhai cruiser, three Type 052D Luyang III destroyers, one Type 052C Luyang II destroyer, one Type 054A Jiangkai II frigate, and a Type 901 Fuyu supply ship—a new large, high-speed auxiliary built to support carrier strike group deployments. It is unknown if a Chinese submarine accompanied the formation.

The cruiser and destroyers’ possessed a total of 352 vertical launch system cells, containing a likely mix of land-attack cruise missiles (CJ-10, range: 1080 nm), anti-ship cruise missiles (YJ-18A, range: 290 nm, or YJ-100, range: 432 nm), and surface-to-air missiles (HHQ-9A or B, range: 81 nm or 108 nm).14 In addition, in April 2022, video emerged of a missile launch from a Renhai cruiser that analysts speculate is a YJ-21 ship-launched ballistic missile, possibly an antiship ballistic missile of undetermined range.15 The ski-jump-launched fighters provide an air-defense umbrella, leaving power projection and striking capabilities—at least for the near term—to Chinese ships and missile-capable submarines.

Deployments of strike groups to the Philippine Sea and elsewhere beyond the first island chain certainly represent a “defense in depth” strategy for the PLAN. With this, PLAN forces can engage advancing fleets at greater range from the Chinese mainland. These deployments also complicate missile-defense geometry for naval forces and bases in Japan, Taiwan, and the Philippines. A diverse array of PLA missiles simultaneously attacking at different speeds from different altitudes already represents an exceedingly complex challenge. Adding missile approach vectors from shooters positioned in the Philippine Sea adds complexity, further challenging purportedly anemic U.S. missile defenses.16 If correct, alleged significant shortfalls in U.S. missile-defense funding and capabilities mean current protections against complex integrated attacks will continue to erode in the face of this increasingly diverse operational geometry.

Doing the Math

China’s navy is evolving at an astonishing rate. The increase in force structure alone offers legitimate cause for concern, if not alarm. A few years ago, China had one aircraft carrier. Now it has three. The PLAN is also clearly pushing out into new operating areas to extend its reach and potentially improve its lethality. However, recent PLAN operations suggest that, for all the rhetoric, the PLAN is still not truly comfortable behind the wheel of its aircraft carriers.

Among the most significant, if underappreciated, factors limiting current PLAN operations is the experience of its personnel. During a trip to the United States with the Chinese chief of naval operations, the first commanding officer of the Liaoning complained to me about the personnel challenges he faced on his ship. Several years into China’s carrier program, for many jobs on board the ship, he had two officers or sailors in each billet. The berthing issues alone were exceedingly frustrating.17 With only one carrier, the Liaoning had to train the entire crew for the second carrier. Now, the Liaoning and Shandong will have to train the entire crew for the third carrier, Fujian.

With a score of aircraft carriers and air wings in its fleet for decades, the U.S. Navy has a deep bench of experienced active-duty personnel from which to draw should it need to create a new aircraft carrier crew. The PLAN is generating experience in carrier aviation—pilots, anticorrosion procedures, flight deck crews, and firefighting protocols—from nothing. In many cases, senior PLAN officers and noncommissioned officers are learning hard lessons at the same time as their junior sailors. The PLA faces the same personnel limitations fielding other technical weapon systems that they are often operating in unfamiliar areas under complicated conditions. The PLA simply cannot scale up its human resources fast enough to meet its emerging operational requirements. That said, the PLA is making cautious progress. The Chinese military recently began a series of personnel reforms, what it calls “talent work,” to address its recognized shortfalls in recruiting, training, and retention.18

As PLAN operational capacities improve and it operates farther from home waters, China will create additional challenges for the United States and its allies. In a potential conflict, U.S. forces will face more sophisticated and complex threats from new vectors as the PLA tries to outflank the U.S. Navy’s distributed maritime operations strategy and the U.S. joint force’s efforts at “expanded maneuver.” Of course, geometry cuts both ways. The PLAN must also be concerned about surviving a coordinated, multiaxis attack. The question may be whether the advantages gained and the risks realized by the changing geometry of these new operating areas drive one side to shoot first in a crisis to retain its advantage.

In the “competition phase” below the level of armed conflict, the changing geometry of PLAN operations will also create new challenges and risks. Chinese forces operating close to other naval forces in unfamiliar areas should be cause for concern. Some Chinese media noted that the Abraham Lincoln Carrier Strike Group was operating in the Philippine Sea during the Liaoning’s May 2022 deployment.19 Neither side has commented on whether U.S. and PLAN forces operated near each other. But a close encounter is inevitable. There should be great concern that the channels of communication both navies enjoyed ten years ago have largely broken down. The potential for miscommunication is significant and may well get worse.

It is doubtful the PLAN is actively seeking conflict with the United States or its allies. But the PLAN will continue to push the envelope, needling the United States, pushing to the point of confrontation without crossing the line to war. This is a dangerous game. Inexperienced PLA personnel operating in unfamiliar areas could push too far; it is unknown how the U.S. Navy will respond if they do. U.S. Navy leaders and operators should pay close attention to the changing geometry of PLAN operations as the tactical proficiency of its personnel continues to improve.

December 2022 Update

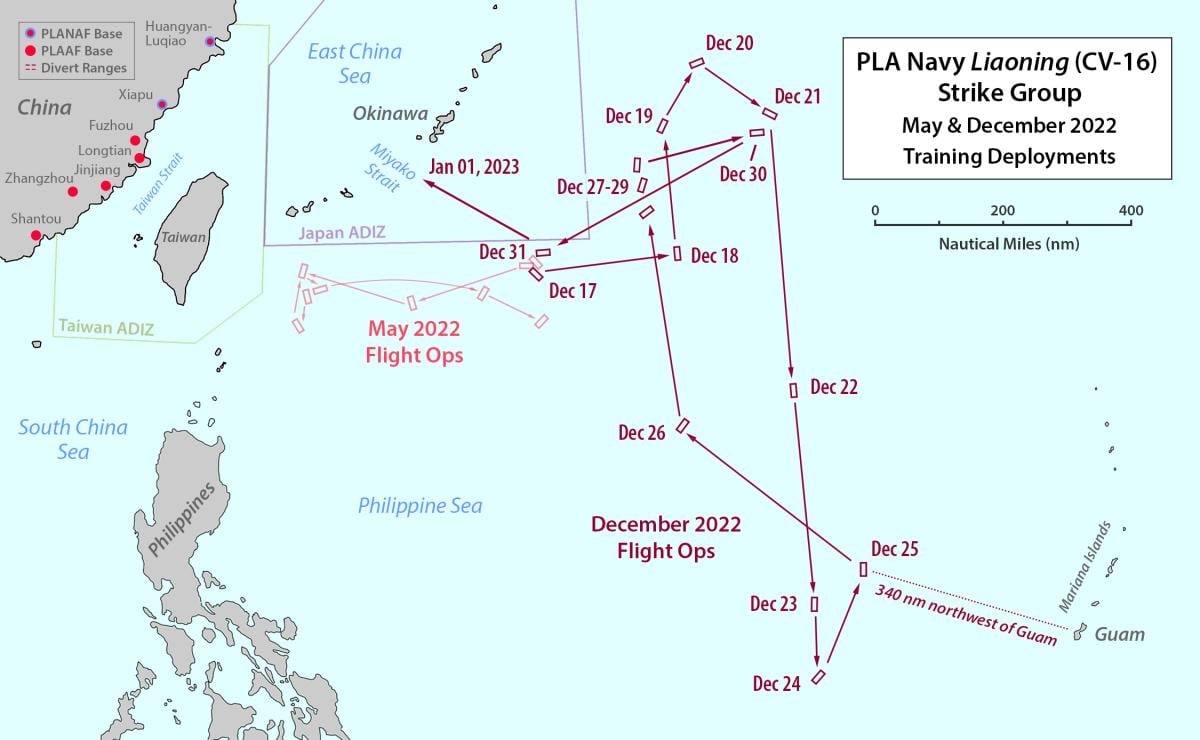

Just as the January 2023 Proceedings and the above article went to print, the PLAN aircraft carrier Liaoning returned to the Philippine Sea for another training deployment. The carrier transited the Miyako Strait on 16 December 2022 accompanied by two Type 055 Renhai cruisers, one Type 052C Luyang II destroyer, one Type 054A Jiankai II frigate, and a Type 901 Fuyu supply ship. The strike group returned to Chinese waters on 1 January 2023.

The Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF) reported that the substance of the December 2022 training appeared very similar to what was observed in December 2021 and May 2022.1 Interestingly, the Philippine Sea carrier training occurred concurrently with a joint China-Russia navy exercise in the East China Sea. Compared to May 2022, the most notable difference in the December 2022 deployment was the range at which the Chinese carrier conducted flight operations. The Liaoning pushed deep into the eastern Philippine Sea. On 23 December, the ship reportedly conducted fixed-wing flight operations 400 nautical miles (nm) from U.S. bases on Guam. These operations truly were “blue water operations”—more than 1,300 nm from the Chinese mainland. PLAN J-15 fighters had no prospects for divert airfields in U.S. Mariana Islands territories or U.S. military protectorates Palau or Yap, just south of the carrier’s operating area.2

Over 15 days, the PLAN carrier reportedly conducted as many as thirte13en days of flight operations in the Philippine Sea. JMSDF reporting indicates that the Liaoning conducted about 20 fighter sorties per fly-day, which is consistent with the earlier Philippine Sea training deployments. J-15s again appeared to fly “clean” or with relatively light air-to-air missiles. No flight operations were reported by JMSDF over the Christmas weekend, 24–25 December, when the Liaoning was farthest from China and closest to Guam.

The Liaoning’s December 2022 deployment will likely be heralded in Chinese media as more evidence of the PLAN’s “combat capability.” Operating a PLAN carrier group just west of Guam was certainly a noteworthy evolution in the geometry of PLAN carrier operations. Still, at those ranges, the Chinese carrier was objectively at a significant disadvantage. The Liaoning’s small air wing could generate only a modest number of sorties with limited airborne radar support from its organic Z-18 airborne early warning helicopter. In a conflict, the Chinese carrier and its escorts would arguably face overwhelming risk from U.S. air power on Guam and from the Nimitz Carrier Strike Group, which was reportedly operating in the Philippine Sea at the time. However, what the PLAN may lack in proficiency, it apparently makes up for by scheduling significant training evolutions on holiday weekends, generating consternation for watchstanders and alert crews and upsetting Christmas and New Year’s “holiday routines.”

1. All PLAN activity and ship positions taken from Japanese Joint Staff, “Movement of Chinese Navy Fleet” press releases, 16–28 December 2022.

2. Palau and Yap were 350 nm and 200 nm south of the Liaoning 24 Dececemberop area respectively. Under the terms of a Compact of Free Association with the U.S., foreign militaries are not allowed to use facilities on Palau or in the Federated States of Micronesia, which includes Yap.

1. Liu Xuanzun and Guo Yuandan, “PLAN’s Liaoning Carrier Group Returns from West Pacific after ‘Longest, Most Sortie-Intensive’ Exercise,” Global Times, 23 May 2022.

2. Liu Xuanzun, “PLA Aircraft Carrier Shandong Holds Drills in South China Sea in Full Combat Group,” Global Times, 25 August 2022.

3. All PLAN activity and ship positions taken from Japanese Joint Staff, “Movement of Chinese Navy Fleet," press releases, 17–21 December 2021 and 2–22 May 2022, www.mod.go.jp/js/press/index.html.

4. Specifications and range information for aircraft taken from Janes references, www.janes.com.

5. Liu Xuanzun, “Chinese Aircraft Get Boost by Fighters’ Nighttime Buddy Refueling Capability,” Global Times, 28 July 2020.

6. Liu and Guo, “PLAN’s Liaoning Carrier Group Returns.”

7. Liu Xuanzun, “Over 100 Aircraft Drill Sorties from Carrier Liaoning in 6 Days near Japan, Taiwan Island ‘Demonstrates Readiness,’” Global Times, 11 May 2022.

8. PEO Aircraft Carrier Public Affairs, “USS Gerald R. Ford Closes Out Evolutionary 18-Month PDT&T for First-in-Class Aircraft Carrier,” press release, 5 May 2021.

9. “The Latest Combat Training of Chinese Navy Liaoning Ship," CCTV Military YouTube channel, 31 December 2021.

10. Japan’s “multipurpose destroyers” Izumo and Kaga do not currently have fixed-wing aircraft on board. Originally built as helicopter carriers, they are being converted to carry F-35s.

11. Taiwan Ministry of National Defense, “Air Situation in Southwest Airspace," press release (Realtime Military Updates), 5–8 May 2022.

12. Japanese Joint Staff, Movement of Chinese Aircraft, press release, 18 May 2022.

13. Liu Xuanzun, “China’s First Carrier-Based Early Warning Plane Continues Flight Tests,” Global Times, 22 February 2021.

14. Specifications and range information taken from Janes references, www.janes.com.

15. “China Unveils World-First Sea Launch Anti-Ship Ballistic Missile,” Chinese Forces YouTube channel, 20 April 2022.

16. See Wes Rumbaugh and Tom Karako, “Seeking Alignment: Missile Defeat in the 2022 Budget,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, 10 December 2021; and John D. Sawyer, Missile Defense (Washington, DC: Government Accountability Office, 2022).

17. To accommodate excess personnel underway and because of a lack of berthing near Chinese shipyards, the Liaoning and Shandong have dedicated “barracks ships,” converted cruise ships that sail with them. See “China’s 2nd Barracks Ship Appears in Dalian,” China Military Online, 16 January 2018, eng.mod.gov.cn/news/2018-01/16/content_4802563.htm.

18. “Talent work”—see "Xi Jinping Delivered an Important Speech at the Central Military Commission Talent Work Conference," Xinhua, 28 November 2021, www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-11/28/content_5653888.htm.

19. Citing the USNI News Fleet Tracker: Liu Xuanzun, “UPDATE: Aircraft Carrier Liaoning Hosts Jet Drills in Philippine Sea, ‘Displays Confidence,’” Global Times, 5 May 2022.