According to noted military historian John Keegan, the Battle of Midway was “an ‘incredible victory,’ as great a reversal of strategic fortune as the naval world had ever seen, before or since.”1 That U.S. victory turned the tide of World War II in the Pacific, just six months after the U.S. Pacific Fleet was mauled by the Imperial Japanese Navy’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor.

Midway’s rightful place in history is secure, and at the center of the lore are the battle’s three victorious aircraft carriers: the USS Yorktown (CV-5), Enterprise (CV-6), and Hornet (CV-8). These three ships, the only available U.S. aircraft carriers in the Pacific, launched the air strikes that wrecked the Kido Butai—Japan’s previously invincible “mobile striking force,” comprised of the aircraft carriers Akagi, Kaga, Hiryū, and Sōryū.2

A significant part of the history around the Battle of Midway was the herculean efforts to repair the Yorktown in time to meet the advancing Japanese fleet. Badly damaged during the Battle of the Coral Sea less than a month prior, she was sent to Pearl Harbor, where her repairs were estimated to require three months—to which Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz famously replied, “We must have this ship back in three days.”3 The Yorktown went straight from the repair facility to join the impending battle with hundreds of men still working to patch her battle damage.4 Her air wing later destroyed the Sōryū and aided Enterprise aircraft in the attack that sank the Hiryū.5

It is easy to wonder if Midway would have turned from victory to defeat if the Yorktown had missed the battle. However, a more important question is: What would have happened at Midway if the Yorktown and her sister ships had not been built at all?

As World War II fades further into the past, the U.S. Navy risks developing a dangerous misperception about its triumph over Japan: Once awakened by the sneak attack at Pearl Harbor, U.S. industrial might built an unstoppable military juggernaut that steamrolled an outmatched enemy. While this rings true for the naval triumphs of 1944 and 1945, the ships that held the line against an ascendant Imperial Japan in 1942 were purchased and built during the interwar years. The Battle of the Coral Sea, Midway, and the Guadalcanal campaign were all fought with ships that made up the “peacetime navy.”

Today, with “the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as our most consequential strategic competitor,” there are lessons to learn from the peacetime investment preceding World War II.6

Naval Power as a Political Choice

The U.S. Navy of 1933 was a shadow of its former self. It had grown to parity with the Royal Navy by the end of World War I, with 774 ships, including 39 battleships, in 1918. However, the fleet quickly aged and dwindled to an interwar low of 308 ships in 1931.7 The Five-Power Treaty for naval arms limitation signed during the Washington Naval Conference of 1921–22 and subsequent London Naval Treaty of 1930 placed limitations on naval construction for the United States and its potential rivals. In addition, domestic political trends toward isolationism and fiscal austerity further limited U.S. naval construction.

While Japan was contriving to exploit treaty loopholes, the United States limited naval construction with the Cruiser Act of 1929.8 Shrinking the Navy by 60 percent reduced the nation’s shipbuilding capacity, as the number of active private shipyards available to support naval construction atrophied from 13 to 7 during the same period.9

The construction of the Yorktown and Enterprise represented a dramatic reversal of this downward trend. They were funded through the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) of 1933 during the first year of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration.10 The act was a fundamental aspect of Roosevelt’s economic New Deal, and the purchase of two modern aircraft carriers was a minor expenditure compared with its other historic measures, such as creating federal protection for collective bargaining rights.11

Contracts for both ships were signed on 3 August 1933—less than two months after the money was allocated—and they were both constructed in Newport News, Virginia. The Yorktown’s keel was laid on 21 May 1934, and she was commissioned on 30 September 1937. The Enterprise followed with her keel laid on 16 July 1934 and her commissioning on 12 May 1938. Both aircraft carriers were built simultaneously in the same yard, with the first vessel commissioned just four years after the initial contract award—a remarkable turnaround by today’s standards.12 In total, the NIRA appropriated twice as much money to naval construction in 1933 as had been done in any year since 1920 and funded 32 new warships.13

Both the Yorktown and Enterprise were purchased far in advance of World War II—funded while the Washington Conference’s Five Power Treaty of 1922 and subsequent 1930 London Naval Treaty arms limitations were still in effect. The Hornet was purchased later with funds from the Naval Expansion Act of 1938—after Japan had withdrawn from the respective naval arms limitation treaties, but before World War II had begun in Europe.14 The Hornet’s keel was laid on 25 September 1939 and she was commissioned 20 October 1941, less than two months before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

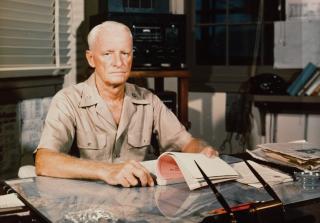

The motivating force behind this reversal of naval fortunes was President Roosevelt. A previous Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Roosevelt was a strong supporter of U.S. naval power in the mold of his fifth cousin, President Theodore Roosevelt. In fact, he often referred to his time “in the Navy” (as Assistant Secretary), relished traveling on U.S. warships, and kept a large collection of model ships.15 Roosevelt understood the United States’ place as a maritime power and the importance of maintaining a strong navy. Furthermore, he believed expanding and modernizing the fleet would serve those national imperatives while simultaneously providing work for thousands of Americans during the Great Depression.16

President Roosevelt was joined in these efforts by Congressman Carl Vinson of Georgia. Vinson led the passage of the Vinson-Trammell Act of 1934, which authorized construction up to treaty limits; the Second Vinson Act of 1938, which significantly expanded and modernized the Navy after Japan withdrew from the naval arms limitation treaties; and the Two Ocean Navy Act of 1940, which built the vast armada that eventually overwhelmed the Japanese Navy in 1944–45.17 This peacetime legislative leadership alongside strong presidential advocacy for the construction of what Vinson called “a first-class Navy for a first-class nation” came just in time—best evidenced by the fact that all three U.S. aircraft carriers had been in commission for less than five years when they won the Battle of Midway.18

Just as important, the large increase in shipbuilding after 1933 primed U.S. industry to build the massive fleet after Pearl Harbor. By 7 December 1941, there were 40 naval shipyards available and more on the way—more than four times the number in 1933.19

Cautionary Tales

Navalists during the interwar period, including Roosevelt and Vinson, were aware of the failed U.S. effort to quickly grow the Navy during the previous world war. Even though World War I had been underway for more than two years before the United States declared war on Germany on 6 April 1917, the U.S. shipbuilding industry was ill-prepared to respond to wartime demands. With the Naval Act of 1916, Congress attempted to make up for lost time, but the resulting shipbuilding efforts were too little, too late.

After building a prewar average of 12.7 naval vessels a year from 1905 to 1915, U.S. shipyards could only marginally increase ship production to 22 in 1916 and 16 in 1917. It was not until 1918, the year hostilities ceased, that the fleet was able to significantly grow by 89 new vessels. Even worse, most of the Navy’s growth in response to World War I was realized with 157 new ships in 1919—the year after the war ended.20

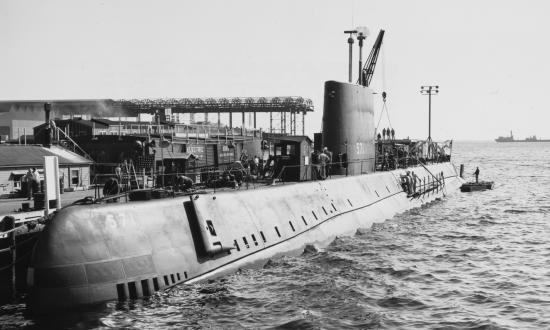

Another World War II naval campaign, fought just months before the Battle of Midway, also warns against relying on an outnumbered and obsolete fleet to defend U.S. interests in distant waters. The U.S. Asiatic Fleet comprised of 45 warships in 1942, almost all of which entered service before the naval expansion efforts of the 1930s. Shortly after the Pacific Fleet was hobbled at Pearl Harbor, the Asiatic Fleet joined the regional forces of the British, Dutch, and Australian navies to form the “ABDA Command” in a desperate attempt to stem the Japanese advance into the Dutch East Indies.

Their doomed effort lasted just two months, from January to February 1942, and provided little resistance to Japan’s expansion at the cost of 18 ships. One of the U.S. casualties was the USS Langley (AV-3)—the Navy’s first aircraft carrier, but subsequently converted to a seaplane tender. Ironically, she was sunk by Japanese aircraft on 27 February 1942, while transporting U.S. Army Air Corps fighter aircraft on her deactivated flight deck.21

A Similarly Precarious State

The modern U.S. Navy finds itself in an eerily similar position regarding shipyard capacity. The United States currently boasts the same number of private shipyards capable of producing new warships as it did in 1933: just seven.22 In addition, the Navy’s four public yards are no longer available for new construction like the ten public yards were in 1933.23

From 2012 to 2021, the U.S. fleet added an average of 10.1 new ships a year—even fewer than the inadequate 12.7 production rate before World War I.24 In fact, the Navy’s current plan as represented in the Report to Congress on the Annual Long-Range Plan for Construction of Naval Vessels for Fiscal Year 2023 (better known as the “30-Year Shipbuilding Plan”) increases naval construction expectations to an average of just 12 vessels per year between fiscal year 2023 and 2027.25 By these metrics, the Navy seems in danger of repeating the errors of World War I’s delinquent shipbuilding efforts—the fate Roosevelt and Vinson successfully avoided with their efforts to expand the fleet in the 1930s.

Today’s relative pace of construction makes early investment even more imperative. While the Yorktown took only four years from contract award to commissioning, modern vessels take much longer. The USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78) took nine years to build and did not deploy for a subsequent five years.26 Granted, the Ford was delayed by the development of multiple technological innovations as the first ship in her class, but the USS Raphael Peralta (DDG-115) took six years to build even though she was the 64th copy of her mature ship class.27 Submarines fare no better. The USS Delaware (SSN-791) commissioned on 4 April 2020—more than 11 years after her contract award date.28 Nuclear power, advanced sensors and weapons, and a reduced domestic shipbuilding industry mean modern warships take much longer to build than their World War II predecessors.

Build Now or Pay Later

Without a massive, predictable boost in U.S. investment in the future navy, the U.S. shipbuilding limitation will not change as it did immediately prior to World War II. Nimitz was willing to risk his precious carriers at Midway in part because he knew reinforcements would soon arrive from an industry prepared to produce warships at scale. A future U.S. admiral may have to face a similar threat knowing that reinforcements are not on the way.29

In contrast, China’s shipbuilding industry is already operating at levels akin to those in the United States in the decade preceding World War II. China’s People’s Liberation Army-Navy (PLAN) grew from 220 to 360 ships between 2010 and 2020 and is expected to expand further to 425 battle force ships by 2030.30 That growth includes China’s first six aircraft carriers in the same way the Yorktown, Enterprise, and Hornet were in the initial cohort of U.S. aircraft carriers built between world wars.

President Roosevelt and Congressman Vinson could not have predicted that the next world war was less than a decade away when they started naval rearmament in 1933, just as contemporary U.S. political leaders can only guess at the future need for the ships they build today. The immediacy of threats has an obvious effect on the importance of investing in tomorrow’s fleet without delay, and China’s threat may be much closer than most expect.

Admiral Phil Davidson famously warned during congressional testimony in March 2021 that “the [China] threat is manifest during this decade, in fact in the next six years.”31 Now known as the “Davidson Window,” the view that China may soon invade Taiwan argues for an immediate and substantial investment to grow U.S. military ability to deter and/or defeat such aggression. If Admiral Davidson’s concerns are taken to heart, the ships funded today may be ready in time to meet this challenge, just as the Hornet proceeded almost directly from her peacetime acceptance trials to combat in the Pacific.32

Admiral Nimitz’s command summary on the eve of the Battle of Midway prophetically stated, “The whole course of the war in the Pacific may hinge on the developments of the next two or three days.”33 Although they did not realize it at the time, President Roosevelt and Congressman Vinson could have made a similar prediction as they set out to rebuild the U.S. Navy in the 1930s: The course of the war in the Pacific hinged on their efforts to rebuild a world-class fleet in the next decade. The Yorktown, Enterprise, and Hornet were just three of the scores of ships that joined the fleet on the eve of World War II, but their fundamental role in winning the war’s most pivotal naval battle makes them the best symbols for the importance of peacetime investment in the Navy.

If U.S. naval dominance is not a birthright, it is also true that U.S. naval superiority stems from an intentional political choice.34 As the Battle of Midway showed, the United States must make the necessary investments in her navy before it is too late.

1. John Keegan, The Price of Admiralty: The Evolution of Naval Warfare (New York: Penguin Books, 1988), 250.

2. Naval History and Heritage Command, “Battle of Midway 4–7 June 1942.”

3. Robert Cressman, That Gallant Ship, U.S.S. Yorktown (CV-5) (Missoula, MT: Pictorial Histories Publishing Company, 1985), 115.

4. Keegan, The Price of Admiralty, 219.

5. Jonathan Parshall and Anthony Tully, Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway (Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2005), 250–61; 326.

6. U.S. Department of Defense, “Fact Sheet: 2022 National Defense Strategy.”

7. Naval History and Heritage Command, “U.S. Ship Force Levels, 1886–present.”

8. CAPT James McGrath, USN, “Peacetime Naval Rearmament, 1933–39 Lessons for Today,” Naval War College Review 72, no. 2 (Spring 2019): 83–103.

9. Philip Koenig and Norbert Doerry, “Industrial Mobilization in World War I:

Implications for Future Great Power Conflict,” 16th Annual Acquisition Research Symposium, Naval Postgraduate School (Monterey, California), 8–9 May 2019, 5.

10. Cressman, That Gallant Ship, 2.

11. National Archives online, “National Industrial Recovery Act (1933).”

12. David Doyle, USS Yorktown (CV-5): From Design and Construction to the Battles of Coral Sea and Midway (Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, Ltd., 2017), 4; Naval History and Heritage Command, National Museum of the U.S. Navy, “19-LC-Box24-Enterprise-Yorktown: USS Enterprise (CV-6) and USS Yorktown (CV-5), 1930s (photo).”

13. McGrath, “Peacetime Naval Rearmament.”

14. David Doyle, USS Hornet (CV-8): From the Doolittle Raid and Midway to Santa Cruz (Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 2019), 4.

15. Craig L. Symonds, World War II at Sea: A Global History (New York, Oxford University Press, 2018), 173–74.

16. McGrath, “Peacetime Naval Rearmament,” 88.

17. McGrath, 88–96.

18. Carl Vinson, “Navy Needs—Extracts from a Speech by Congressman Vinson,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 58, no. 4 (April 1932).

19. McGrath, “Peacetime Naval Rearmament,” 91.

20. Koenig and Doerry, “Industrial Mobilization in World War I,” 4.

21. W. G. Winslow, The Fleet the Gods Forgot: The U.S. Asiatic Fleet in World War II (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1982), 299–304.

22. McGrath, “Peacetime Naval Rearmament,” 96.

23. Shipbuildinghistory.com, “U.S. Naval Shipyards and Bases.”

24. Congressional Research Service, Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress, 16 September 2021.

25. Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Warfighting Requirements and Capabilities, Report to Congress on the Annual Long-Range Plan for Construction of Naval Vessels for Fiscal Year 2023, April 2022, 13–16.

26. Naval Vessel Register online, “USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78): Multi-Purpose Aircraft Carrier (Nuclear-Powered).”

27. Naval Vessel Register online, “USS Rafael Peralta (DDG-115): Guided Missile Destroyer.”

28. Naval Vessel Register online, “USS Delaware (SSN-791): Submarine (Nuclear-Powered).”

29. CAPT James McGrath, USN, “Would Nimitz Win a Midway Today?” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 144, no. 6 (June 2018).

30. Congressional Research Service, China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress, 8 March 2022, 9.

31. Mallory Shelborne, “Davidson: China Could Try to Take Control of Taiwan in ‘Next Six Years,’” USNI News, 9 March 2021.

32. Naval History and Heritage Command, “Yorktown III (CV-5): 1937–1942.”

33. McGrath, “Would Nimitz Win a Midway Today?”

34. CDR Benjamin Armstrong, USN, “American Naval Dominance Is Not a Birthright: Dominance at Sea Depends on the Navy’s Relationship with the American People,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 147, no. 9 (September 2021).