Submarines have repeatedly proven their versatility in great power combat. When commanders needed a convoy destroyed, a garrison evacuated, or a downed pilot rescued, submariners flexed to accomplish the mission, often achieving the task when no other platform could.

As the U.S. Navy prepares for future high-end combat, commanders will again have a highly capable and flexible submarine force at their disposal, able to use nuclear power and advanced technology to accomplish an even wider array of missions. However, just because a submarine can accomplish a mission does not mean it should, and just because the mission can only be accomplished using a submarine does not mean it should be accomplished at all. Just as periscopes can only look at one target at a time, submarines can generally only execute one mission at a time. Commanders will need to choose wisely, because if the periscope is pointed at one target, it is not focused on any others.

As the Navy searches for the best use of its undersea fleet in high-end combat, a review of history shows that when submarines have a clear strategic goal—typically sea denial—it is rarely worthwhile to divert them to perform secondary tasks. They excel at destroying enemy shipping and are ill-suited to most other roles. That examination provides insight into steps the Submarine Force can take today to be ready to sweep the seas of enemy ships tomorrow.

Submarines in Great Power Combat

Kriegsmarine in World War II. “England was in every respect dependent on sea-borne supply for food and import of raw materials, as well as for development of every type of military power,” Admiral Karl Doenitz told the Office of Naval Intelligence following World War II. “The single task of the German Navy was, therefore, to interrupt or cut these sea communications.”1

Although their prospects were slim, the Kriegsmarine’s best chance of achieving that goal was early in the war, before the Allies developed robust antisubmarine warfare (ASW) capabilities. Even though Adolf Hitler himself declared, “The submarine war will in the end decide the outcome of the war,” he and the Oberkommando der Marine (OKM, or Navy High Command) frequently intervened to use U-boats for missions for which they were ill-suited, reducing Germany’s already poor chances of winning the Battle of the Atlantic.2

In the 1940 invasion of Norway, Doenitz sent 31 U-boats to defend amphibious landings, deliver supplies and fuel, and interdict enemy warships. However, in restricted waters with poor weather and terrible torpedo performance, these U-boats achieved little and four were lost. To concentrate the necessary force, Doenitz used all available sea-going units, broke off sea trials for two new boats, and temporarily stopped training to send six Submarine School boats.3 Thus, essentially all Atlantic patrols ceased for three months with little to show for it.

Eight boats deployed to the Baltic when Germany invaded Russia the following year, where they “found practically no targets and accomplished nothing worth mentioning,” and several more to the Arctic, where they “roamed the empty seas,” according to Doenitz.4 In the Mediterranean, U-boats achieved some success, but still likely did not justify their use in the secondary theater; between January and April 1942, 21 U-boats in the Mediterranean sank only six confirmed ships.5

In addition to being used in secondary theaters, U-boats were also used for secondary missions. They delivered Abwehr (intelligence) agents, most of whom yielded no benefit. They escorted German warships and commerce raiders, despite, as Doenitz wrote, that “the U-boat would stand very little chance of being able to protect its charge if it were attacked and would be quite powerless to help if it were sunk.”6 U-boats were removed from offensive patrols to submit weather reports for the Luftwaffe at a time when there were typically fewer than 10 operational submarines on patrol at a time.7

These operations forced the Allies to spread their forces and yielded some tactical victories. However, they typically were not beneficial enough to justify the diversion of U-boats from attacks on British supply lines. As Doenitz wrote in his War Diary, “The decisive factor in the war against Britain is the attack on her imports. The delivery of these attacks is the U-boats’ principal task and one which no other branch of the Armed Forces can take over for them.”8 Any chances the Germans had to execute that task early in the war were lost when the OKM directed dozens of U-boats to execute missions for which they were poorly suited at the cost of the sea denial mission for which they were designed.

Imperial Japanese Navy in World War II. The primary focus of the Imperial Japanese Submarine Force early in the Pacific War was to sink U.S. warships and merchants to protect Japanese territorial gains. In 1942, Japanese submarines performed this function reasonably well. In a year that U.S. submarines managed to sink only two cruisers, Japanese submarines sank two carriers and a light cruiser while also damaging another carrier, a battleship, and a heavy cruiser.9

However, by late 1942 the strategic picture had changed. Japanese ground forces were struggling to hold on at Guadalcanal, and so Japanese leaders directed submarines to serve as transports. Thirteen fleet-type submarines delivered approximately 1,000 tons of supplies to Guadalcanal while evacuating approximately 2,000 troops, yet four boats were lost in the process.10 Throughout the rest of the war, the Japanese submarine fleet primarily executed resupply and evacuation missions for stranded garrisons, with disastrous results both for the boats’ survival and their ability to execute the sea denial mission. In 1943, Japanese submarines sank only three U.S. warships: a jeep carrier, a submarine, and a destroyer.11 As Kennosuke Torisu, a Japanese submarine captain and staff officer during the war, wrote, “This blunder in submarine employment was hard to remedy.”12

When Japanese submarines were freed from those missions, they were still often diverted from sea-denial missions to futilely execute coastal defense operations or mini-submarine attacks. Admiral Charles Lockwood, the Pacific Fleet Submarine Force Commander for much of the war, wrote that mini-submarine construction was a “sideshow” that “seemed like wasted effort.”13

U.S. Navy in World War II. The U.S. Submarine Force’s primary mission in World War II was to cut off the flow of supplies and oil to Japan. However, the three Pacific submarine commands failed to identify this strategic aim early in the war, even though the Japanese had attacked the U.S. largely to assure its access to vital supplies of oil and raw materials.14

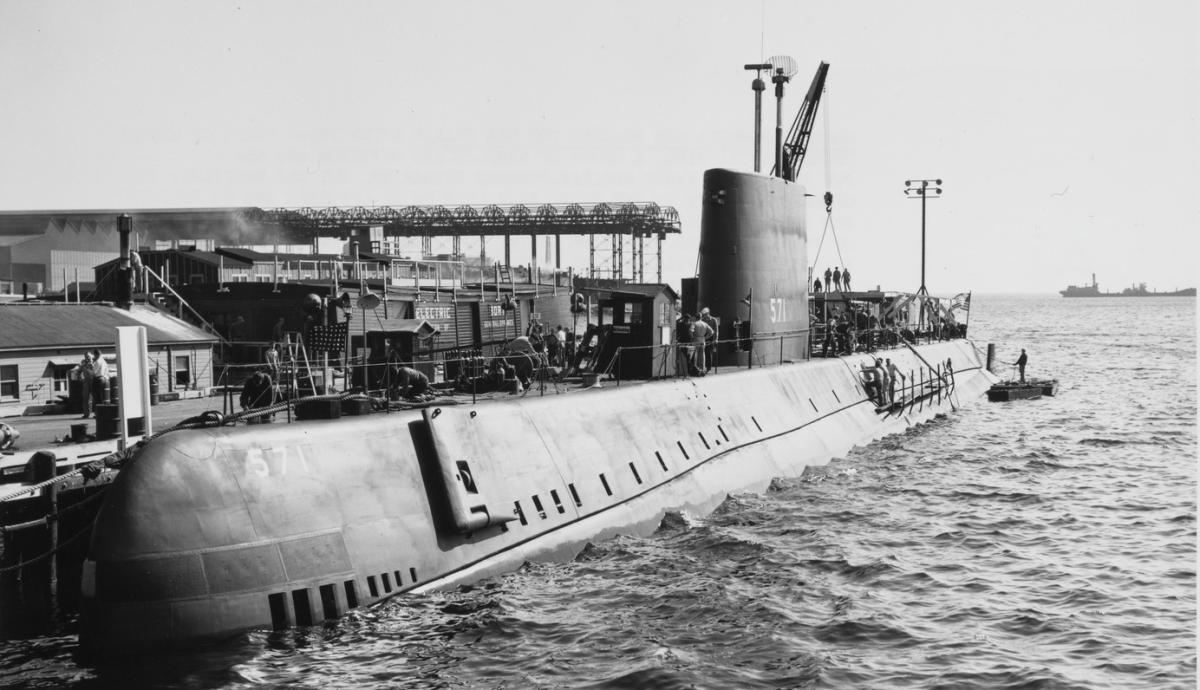

As a result of the lack of a clear focus, it became easier to use submarines for a wide variety of disjointed tasks. They conducted patrols in far-flung locations, such as when 17 boats operated off the Aleutians in 1942, combining to sink just two destroyers and one freighter.15 They moved meager amounts of supplies, such as when USS Seawolf (SS-197) offloaded 16 torpedoes to deliver 72,585 pounds of .50 caliber and 3-inch ammunition to General Douglas MacArthur’s forces on Corregidor, a delivery that “amounted to about one day’s supply,” according to Seawolf’s captain.16 They conducted commando raids, like when USS Nautilus (SS-168) and USS Argonaut (SS-166) offloaded most of their weapons and converted to troop transports to launch the botched Makin Island raid.17 Meanwhile, during the first year of the war, U.S. submarines executed just 15 percent of their war patrols in the most fruitful and strategically important waters, near Japan and Formosa. Those few patrols accounted for 45 percent of all sinkings that year.18

When the Submarine Force focused on cutting off supplies to the Japanese islands, its boats—finally armed them with effective torpedoes and led by aggressive captains—achieved devastating results. By the end of the war, they had sunk 1,113 merchant ships for more than 4.7 million tons.19

Argentinian Navy in the Falklands War. In the 1982 Falklands War, the Argentinian Navy’s primary focus was to prevent British sea control and thus stop them from retaking the Falkland Islands. Throughout the war, the Argentinian Submarine Force only had two operational boats to contribute to that mission, yet it sent one of them to deliver reinforcements to the island of South Georgia. On 25 April, ARA Santa Fe was on the surface just after delivering the troops when British ASW helicopters attacked the submarine, forcing the crew to beach their damaged ship.20

That left a single operational submarine, ARA San Luis. It did not even sink any ships on its patrol, yet its mere presence affected British fleet disposition, altered operational plans, and led the Royal Navy to launch 200 torpedoes at false contacts.21

Thus, San Luis, focused on the sea-denial mission, “created enormous concern for the British,” according to a former commander of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet. “It dictated, at least as much did the air threat, the conduct of British naval operations.”22 On the other hand, in what the British Task Force Commander Admiral Sandy Woodward called “a miracle,” Santa Fe was lost delivering an inconsequential number of troops to a remote outpost; British forces still captured the island later that same day.23

Focusing Submarines on the Right Missions

The history of undersea warfare in great power combat indicates that submarines have often been poorly used. In the sea-denial role, a submarine is “a first class weapon of offence in naval warfare,” as Doenitz wrote.24 On the other hand, submarines are only marginally effective at many other missions. They can carry only small amounts of material for resupply missions, just a few dozen troops for special operations forces (SOF) insertion, and their poor scouting ability and communication capability mean they have often struggled in the coastal defense and fleet scout role. Most importantly, submarines’ limited space and posture allows them to typically execute just one mission at a time, meaning changes in operations incur high opportunity costs.

This is not an absolute rule, as there have been many cases of submarines conducting worthwhile secondary operations. For example, U.S. submarines on “lifeguard” duty rescued dozens of downed aviators throughout World War II. However, there was little cost to diverting the submarine’s focus; they did not need to offload weapons, could continue their war patrol, and primarily executed the mission late in the war when there were increased numbers of U.S. submarines and few Japanese ships left to sink. Overall, in a future conflict, commanders should think twice before using a submarine for a wartime mission other than sea denial. Submarines, originally focused on antisurface warfare (ASUW), are now key platforms for ASUW, ASW, mine warfare, clandestine strike, subsea and seabed warfare, SOF insertion, and intelligence collection, but just because they can perform more missions does not mean they should.25

Submarine Forces command is already taking steps to ensure its boats are used appropriately in combat. It has argued against deploying submarines with carrier strike groups. It is addressing command-and-control issues that have led to improper submarine employment in the past, such as split operational commands, MacArthur’s frequent demands for submarine special missions, and what Doenitz described as a “complete lack of understanding, particularly by our political leadership, of the essential characteristics of U-boat warfare.”26 Under the Theater Undersea Warfare Commander (TUSWC) construct, there is a single undersea domain commander who understands the proper use of submarines and is better able to advance the combatant commander’s aims while resisting outside pressures for extraneous submarine services.27

Yet the real challenge will happen when the bullets—and torpedoes—start flying. The Japanese did not envision converting their attack boats to supply ships and the Germans did not intend to use their U-boats as weather stations. The difficult task for TUSWCs will come when SOF leaders want their forces inserted, the Army demands resupply for its isolated troops, the Air Force requests “lifeguard” submarines for its pilots, and the surface fleet orders protection for its aircraft carriers. Then TUSWCs will need to make hard choices, acknowledging that all those missions have value but likely not as much as sending submarines to sweep the seas of enemy warships.

Preparing Submarines for Those Missions

Focused on the wrong missions, using overly conservative tactics, and employing defective weapons, the U.S. Submarine Force was not well prepared for great power combat in 1941. Despite weak Japanese ASW efforts, many submarine COs failed to achieve results, and 30 percent of them were relieved by the end of the 1942.28 The U.S. Submarine Force cannot afford to repeat that failure; its forces must be ready to fight on day one.

Fortunately, the submarine force has taken important steps to better prepare for combat. It has refocused the primary tactical evaluation as the Combat Readiness Evaluation, trimming extraneous tasks to concentrate on primary warfighting mission areas. “Fight Clubs” pit submarine crews against each other in competitive combat scenarios. An “Aggressor Squadron” now trains the fleet on adversary platforms, weapons, and tactics. Throughout the force, there is a renewed focus on maximizing readiness and combat potential.

With the threat of great power combat growing, it is time to build off those successes. These changes will not be easy, but because the submarine force has already picked all the low-hanging fruit, it is time for fundamental changes to realize fundamental improvements.

Specialize Submarine Officers Into SSN- and SSBN-Centric Corps. To execute the strategic deterrent and fast-attack missions, the Navy uses specialized submarine classes tailored to the mission instead of a common hull. The Navy uses customized weapons for strategic deterrence, conventional land attack, and ASW, realizing the gains of specialization outweigh the costs of differentiation. In contrast, the officers commanding those specialized hulls employing those specialized weapons are generally interchangeable. As a result, officers are unable to develop the same breadth of experience and expertise they could if they specialized in either challenging mission. Doctors practice a specialty, baseball players play at a particular position, and submarine officers should focus on either the SSBN or SSN mission to become masters of their profession. It does not need to be an absolute separation, but after the department head tour it is likely time to focus on one area instead of continuing to be a jack of all trades.

Solve the Unsolvable Shipyard Dilemma. History has shown how important it is to focus submarines on the right mission, but for huge portions of submariners today, the only mission that matters is shipyard availability. With the Navy’s shipyards completing just 15 percent of submarine availabilities on time between 2015 and 2019, boats such as the USS Boise (SSN-764), Helena (SSN-725), and Columbus (SSN-762) remaining offline for years longer than planned, and officers routinely completing entire tours without ever going to sea on their own ships, the problem is only getting worse.29 In the long term, the only solution appears to be opening another public shipyard, as the Navy’s maintenance workload will exceed its shipyards’ capacity in 25 of the next 30 years.30 That will alleviate the backlog of submarine availabilities, provide surge capacity for battle-damaged ships, and give shipbuilders the capacity to build three SSNs per year—an impossible goal today.

In the meantime, the Navy can free some of those submarine officers in shipyard purgatory so they can better prepare for what only they can do—fight their ships at sea. In major availabilities, the Navy should shift some responsibilities from unrestricted line (URL) officers to the engineering duty officers and civilian shift test engineers, both better trained and more experienced in that role. Whether that frees officers for months to deploy on other submarines, or just for hours to go to more trainers, it will result in a more tactically adept force ready to execute crucial wartime missions. Submariners should not be sacrificed in years-long maintenance periods if the Navy expects them to be tactical experts when war erupts.

When submarine officers switch between SSBNs and SSNs, or return to sea after years in the shipyard, they use their training, intelligence, and work ethic to perform well in their new roles. However, they are unable to perform as well as they could if they had more experience in that role. In a fight against China or Russia, the United States will need every possible advantage and specializing officers will help make a great officer cadre even better.

Reduce SSN Global Force Management (GFM) Requirements. Exercises are one of the best ways to prepare crews for the sea-denial mission, allowing them to “develop the foundational tactical skills” and “experience and sound judgment required to win,” as the Submarine Force leadership wrote.31 However, the submarine force can only participate in exercises if it can meet GFM requirements for deployed submarines. As the number of idle and shipyard boats increases, the remaining operational boats will have less ability to participate in exercises, instead having to accomplish certification milestones on the way to deployment.

A moderate reduction in GFM requirements—a blasphemous proposition for combatant commanders—would provide submarines more opportunities to participate in premier exercises like Black Widow and Fleet Battle Problems. It would help balance the Navy’s missions of deploying to deter aggression and being ready for high-end combat if that deterrence fails.

On the Scope, Beware the Shiny Object

Just as shiny objects distract periscope operators from the primary target, history shows that secondary missions often divert submarines from their primary task—sea denial.

Applying that, wartime TUSWCs fight extraneous tasking that keeps submarines from destroying enemy warships. Today’s force can better prepare its boats for that fight by specializing SSBN and SSN officers, increasing shipyard capacity and shifting shipyard responsibilities away from URL officers, and reducing GFM demands. Enacting these recommendations will be difficult, but submarine force leaders have already seized most opportunities that are easier to realize. To build on those successes, larger changes are needed if the Navy hopes to achieve greater improvements in combat potential.

1. Admiral Karl Doenitz, “The Conduct of the War at Sea.” (Washington, D.C.: Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, Division of Naval Intelligence, 15 January 1946), 21.

2. Clay Blair. Hitler’s U-Boat War. Volume II, The Hunters, 1939-1942 (New York: Modern Library, 1996), 564.

3. Grand Admiral Karl Doenitz, Memoirs: Ten Years and Twenty Days (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2012), 77.

4. Doenitz, Memoirs, 153.

5. Blair. Hitler’s U-Boat War, 555.

6. Doenitz, Memoirs, 153.

7. Ibid., 105.

8. Ibid., 153.

9. Clay Blair, Silent Victory: The U.S. Submarine War Against Japan (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2001), 360-361.

10. Carl Boyd and Akihiko Yoshida, The Japanese Submarine Forces and World War II (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1995), 105.

11. Blair, Silent Victory, 553.

12. Kennosuke Torisu, assisted by Masataka Chihaya, “Japanese Submarine Tactics,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 87, no. 2 (February 1961).

13. Vice Admiral Charles Lockwood, USN (Ret.), Sink ‘Em All (Columbia, SC: Rocket Press, 2018), 23.

14. Peter Padfield, War Beneath the Sea: Submarine Conflict During World War II (New York: John Wiley & Son, Inc., 1995), 193-194.

15. Blair, Silent Victory, 359-272.

16. “USS Seawolf (SS-197), “Third War Patrol Report,” 7 February 1942, 4.

17. “USS Nautilus (SS-168), Second War Patrol Report.”

18. Blair, Silent Victory, 359-361.

19. The Joint Army-Navy Assessment Committee, “Japanese Naval and Merchant Shipping Losses: During World War II By All Causes.” (February 1947), vii.

20. Max Hastings and Simon Jenkins, The Battle for the Falklands (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1983), 129.

21. Lawrence Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign. Volume II, War and Diplomacy. (London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2005), 214, 728.

22. Admiral Harry D. Train II, USN (Ret.), “An Analysis of the Falkland/Malvinas Islands Campaign,” Naval War College Review, Winter 1988, 40.

23. Admiral Sandy Woodward, One Hundred Days: The Memoirs of the Falklands Battle Group Commander (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1992), 105.

24. Doenitz, Memoirs, 13.

25. Vice Admiral Daryl Caudle, USN, and Rear Admiral Blake Converse, USN, “Commander’s Intent 3.0: U.S. Submarine Force and Supporting Organizations.” (September 2020), 10.

26. Link.

27. Doenitz, Memoirs, 152.

28. Caudle, “Commander’s Intent 3.0,” 22.

29. Peter Padfield, War Beneath the Sea: Submarine Conflict During World War II (New York: John Wiley & Son, Inc., 1995), 191.

30. Government Accountability Officer, “Navy Shipyards: Actions Needed to Address the Main Factors Causing Maintenance Delays for Aircraft Carriers and Submarines.” (Washington, D.C.: United States Government, August 2020), 10.

31. Congressional Budget Office, “The Capacity of the Navy’s Shipyards to Maintain Its Submarines.” (Washington, D.C.: Congress of the United States, March 2021), 1.

32. Caudle, “Commander’s Intent 3.0,” 8.