Ultra-long-duration balloons are a subset of high-altitude balloons (HABs) that can operate for extended periods as high as 120,000 feet, into the stratosphere. Should the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) attempt to invade Taiwan, sea mines—deployed in critical choke points—will be among the tools best tailored to blunting the attack; joint doctrine says the objective of mining is to “reduce the adversary’s threat to friendly forces and preserve freedom of action.”1 Unfortunately, the Sea Services and U.S. Air Force may not be able to deliver many mines. Nuclear submarines, Air Force bombers, and maritime patrol aircraft are low-density, high-value capabilities that will be tasked with other missions farther from China. HABs offer a potential solution.

The Sea Services should develop a balloon-based mine delivery system because of its increased capability and capacity and reduced cost and risk compared with existing mine deployment systems. HABs could prove a valuable complement to the Navy’s Extra Large Unmanned Undersea Vehicle (XLUUV) Orcas, while providing additional capacity across numerous warfare areas. HABs are a proven capability that could be adapted for military use, scaled economically, and impose greater costs than current systems while remaining in line with associated doctrine.2 The Navy and Marine Corps must consider balloons for mine warfare.

The Deflating Reality

In “An Offensive Minelaying Campaign against China” in the winter 2022 Naval War College Review, Matthew Cancian argues that, in a war with China, “the American bomber arsenal . . . could lay between 840 and 3,880 mines at one time . . . while historical cases show that each of China’s twenty available minesweepers could clear an average of 0.8–2 mines per day,” delaying operational freedom of maneuver for the PLA for at least three weeks—and possibly many months. But the argument depends on “no ongoing exchange of fire” and bombers flying freely to deploy a minefield that will subsequently be announced by the United States to encourage a peaceful resolution of a burgeoning China-Taiwan crisis. Others propose a Taiwan mine defense that depends on “UUVs . . . submarines . . . aircraft or uncrewed aerial vehicles . . . [and] surface ships or uncrewed surface vessels to distribute mines.”3

The PLA’s well-publicized antiaccess/area-denial systems diminish or eliminate the value of carrier-based aircraft deploying mines, and the Navy’s Naval Aviation Vision 2030–2035 report makes no mention of it in any case. At the outset of a Sino-American war, only a handful of submarines and bombers might be available in theater, and they might serve better by sinking ships with torpedoes and cruise missiles instead of hoping that submarine-launched mobile mines (which the Virginia-class cannot launch) and air-launched mines can achieve the same outcome.

Further, the XLUUV program is nearly a quarter-billion dollars over budget and three years behind schedule, and the earliest weaponized unmanned surface vehicle program of record will not be bought until fiscal year 2025.4 The P-8A Poseidon, which can deploy the Quickstrike glide mine, must deal with readiness issues, a global demand, and a possible Chinese submarine force of 76 boats by 2030.5 Only limited capacity and opportunity for growth exist among the high-demand platforms tapped for mining.

Looking Up

The Chinese spy balloon that captivated the nation in April was only the latest demonstration of increasingly capable HAB technology. Today’s super-pressure, ultralong-endurance balloons are typically made from a thin, lightweight polymer coated with titanium dioxide to protect against the harsh conditions of the stratosphere. The balloons are filled with a mixture of gases, including helium and hydrogen, which allows them to maintain constant internal pressure and stay airborne for months at a time. They are a cost-effective alternative to satellites and have been used to study a variety of phenomena, including cosmic rays, atmospheric chemistry, and global climate change.

They also could make valuable mine-deployment vehicles. Google’s now-canceled Loon system proved the underlying technology, which relies on accurate weather data, artificial intelligence, and machine-learning algorithms to manage altitude to catch the right upper-atmospheric conditions for navigation. Loon’s HABs spent as many as 312 days aloft, and some even circumnavigated the globe, while others traveled as fast as 201 miles per hour.6

A HAB Against Orcas

Launched from as far away as the continental United States, HABs need not operate within the weapon engagement zones of China’s myriad conventional strike systems to deploy their mines. Balloons are orders of magnitude less expensive than the bombers, submarines, and unmanned craft that supposedly will fill the offensive mining role. As Reuters notes: “Each [Loon HAB] cost tens of thousands of dollars and must be replaced every five months as their plastic shells degrade,” while overall launch and system costs can be in the hundreds of thousands of dollars—enabling greater scale and capacities in lightly tapped sectors of the defense industrial base.7

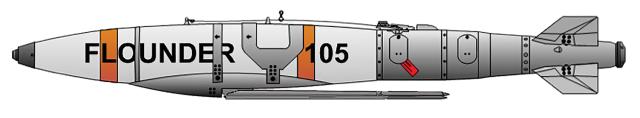

There are tactical benefits to HAB mine deployment. Quickstrike–Extended Range (QS-ER) mines “glide approximately 40 nautical miles from the launching aircraft when dropped from 35,000 feet.”8 That horizontal distance divided by the vertical drop provides a glide ratio of 6.94. That suggests a 500-lb QS-ER dropped from 120,000 feet might glide 137 nautical miles. This rough calculation does not account for wind, air density and pressure, launch velocity, etc., but it is clear HABs would double or triple the range from which QS-ERs could be launched.

Compare this to the XLUUV Orca. The Orca program’s fiscal year 2023 $621 million budget request should result in five prototypes (roughly $110 million each) and a $73 million test vehicle.9 Forbes reports that the Orca’s payload is eight tons, with the capacity to lay dozens of mines during a single mission.10 But consider available mines. The new Hammerhead’s weight is unknown, but the system is broadly similar to the submarine-launched Encapsulated Torpedo (CapTor), whose weight is 2,056 lbs; the Mk 67 Submarine Launched Mobile Mine (SLMM) weighs 1,658 lbs.11 An Orca could deploy only about 8 Hammerheads and 10 Mk 67s. It could deploy roughly 32 500-lb Mk 62 Quickstrikes, totaling at most 160 mines from 5 XLUUVs.

Though pricing for newer balloons from NASA and Raven Aerostar is unavailable, consider a generous estimate of $250,000 for a HAB system with an 8,000-lb payload. A HAB minelayer might be able to carry 6,000 lbs of mines plus a 2,000-lb control, communication, and power module. The $548 million for five Orcas would pay for more than 2,000 HAB minelayers, each able to deploy a dozen 500-pound QS-ER mines from an altitude of 120,000 feet and a distance of more than 100 nautical miles. That many HABs could deliver perhaps 25,000 mines in total—more than 160 times the five Orcas’ capacity—while a single Orca might cost 438 times as much as a single HAB.

A critic might contend that the Orca is covert. However, even if all the Orcas could bypass all Chinese defensive mining around the Taiwan Strait, seabed underwater sensors, and an increasingly capable (or at least large) antisubmarine warfare capacity, HAB mine deployment systems are superior—they have a global range and could fly above the reach of many Chinese surface-to-air missiles. China’s HQ-9 land and HHQ-9 sea-based surface-to-air missile systems have a maximum altitude capability of 27 kilometers (88,582 feet).12 Even the upgraded HQ-9B and HHQ-9B are reportedly limited to about 30 km (98,425 feet).13

Consider the Chinese spy balloon experience: The U.S. Air Force spent at least $1.5 million on missiles and was forced to “enhance their radars and expand their filters” to intercept and shoot down three high-altitude objects in early 2023.14 Even if a broad collection of Chinese weapons were somehow able to strike discrete, distributed, and plentiful near-space balloons, that would deplete China’s inventory of its most capable air-to-air and surface-to-air missiles that might otherwise be used against U.S. and Taiwanese aircraft.

Fundamentally, HABs are highly capable systems with multiple possible uses: deploying freefall general-purpose bombs, Joint Direct-Attack Munitions (JDAMs), and the new Quicksink weapons (modified JDAMs); airborne early warning, sonobuoy deployment; intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, and targeting; and providing communications and navigation data. But even limited to laying mines, HABs should play a prominent role in controlling key maritime territory and contribute to distributed maritime operations. Mine deployment systems such as Orca, on the other hand, are high-risk, high-cost, and low-density and have long lead times. Deployed in sufficient numbers, balloons could cause the sort of havoc for PLA plans that a single spy balloon caused for an extended media cycle.

1. Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Publication 3-15: Barriers, Obstacles, and Mine Warfare for Joint Operations, Washington, DC, 5 March 2018.

2. LCDR Collin Fox, USN, “If It Floats, It Fights,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 144, no. 6 (June 2018).

3. Scott Savitz, “Defend Taiwan with Naval Mines,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 149, no. 2 (February 2023).

4. Sam LaGrone, “GAO: Navy’s XLUUV Undersea Minelayer $242M Over Budget, 3 Years Behind Schedule,” USNI News, 28 September 2022; and Congressional Research Service, “Report on Navy Large Unmanned Surface and Undersea Vehicles,” 1 September 2022.

5. Richard R. Burgess, “Navy Orders Quickstrike–Extended Range Glide Kits for Sea Mines,” Seapower, 23 July 2021; “Pentagon Report on P-8A Readiness for Anti-Submarine Warfare Mission,” USNI News, 25 May 2021; and Xiaoshan Xue, “China’s Expanding Submarine Fleet Makes Experts Worry about Taiwan’s Readiness,” VOA News, 19 August 2022.

6. Dale Smith, “Alphabet’s Loon Sets Record for Stratospheric Flight by a Balloon,” CNET, 28 October 2020; and Brent Rose, “The Incredible Calculations That Keep Google’s Project Loon Aloft,” Gizmodo, 29 May 2015.

7. Paresh Dave, “Google Internet Balloon Spinoff Loon Still Looking for Its Wings,” Reuters, 1 July 2019.

8. Burgess, “Navy Orders Quickstrike.”

9. LaGrone, “GAO: Navy’s XLUUV Undersea Minelayer.”

10. David Hambling, “With Hammerhead Mine, U.S. Navy Plots New Style of Warfare to Tip Balance in South China Sea,” Forbes, 22 October 2020.

11. “Mines of the United States of America,” Navweaps.com, 23 September 2022.

12. “HQ-9 Long-Range Air Defense Missile System,” Military-Today.com.

13. Tong Ong, “China Puts Upgraded HQ-9 Missile System to ‘Extreme Test,’” Defense Post, 24 May 2021.

14. Nancy A. Youssef and Aruna Viswanatha, “Pentagon Spent at Least $1.5 Million on Missiles to Down Three High-Altitude Objects,” Wall Street Journal, 22 February 2023; and John Hill, “NORAD Expands Sensory Filters of Aerial Intrusion over North,” Air Force Technology, 13 February 2023.