The 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine has involved the largest use of land-attack missiles in history, with launches from all basing modes. On 21 March, the Pentagon stated that the “Russians have launched more than 1,100 missiles,” and that “they have also suffered a not-insignificant number of failures of those munitions.” Four days later, the Pentagon added that “they’re still launching a lot of missiles,” but Russia was experiencing “a significant amount of [missile] failure” including “failure to actually launch or failure to hit the target.”

On 4 April, the Pentagon claimed Russia had launched more than 1,400 missiles and that its residual inventory is the lowest in cruise missiles. In late May, Ukrainian President Volodomyr Zelensky stated that Russia had launched 2,154 missiles and Ukraine believes Russia has depleted 60 percent of its precision-missile arsenal. Since April, resupply has been difficult and inventory depletion has continued.

This very large expenditure of missiles was clearly not planned because Russia expected a quick victory. Russia’s efforts to replace its missiles will be very difficult because of cost, production limitations, and the impact of the sanctions. Worse still, from a Russian standpoint, is that the attacks have demonstrated there are significant problems with the performance of Russian cruise missiles.

Excessive Failure Rate

On 25 March, the Pentagon confirmed press reports that various Russian missiles were experiencing failure rates of 20 to 60 percent (failure was defined as the inability to launch or hit the target) with “cruise missiles, particularly air-launched cruise missiles” having the lowest kill rates. Reportedly, some missiles did not explode even when they hit their targets. Thus, in addition to the reliability and quality control problems with the missiles, they apparently have a fusing problem.

On 10 May, the Pentagon confirmed that Russia had depleted its missile inventory and that it was “running through their precision-guided missiles at a pretty fast clip” and was “running the lowest on cruise missiles, particularly air-launched cruise missiles,” but Moscow still had more than 50 percent of its prewar inventory. Since then, missile use has continued, but at much-reduced rates.

Inflated Expectations

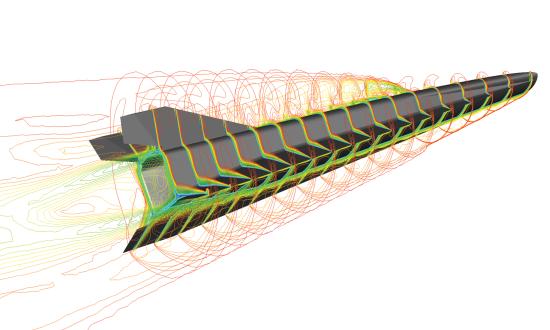

For a long time, the Russian military has claimed that its nonstrategic ballistic and cruise missiles and strategic long-range cruise missiles have accuracies measured in a few meters. Former Deputy Prime Minister Yury Borisov (now head of Russia’s Space Agency), who handled defense procurement, stated that the Kh-101, Bastion, Bal, Kalibr, Iskander (hypersonic at longer ranges), and Kinzhal hypersonic missiles were high-precision missiles and that “high-precision munitions have the error probability of just a few meters. They can travel hundreds of kilometers and have next to zero CEP.” Even before the war, there was some evidence that this was not the case.

In 2017, a noted Russian military journalist pointed out in state media that the Kalibr naval cruise missile had an accuracy of 30 meters and the Kh-101 air-launched cruise missile had an “accuracy of five to 50 meters,” which is quite different than a “few meters” or near-zero CEP. While the variation in accuracy is not explained, 50 meters is not even close to near-precision accuracy. In January 2022, U.S. Army Chief of Staff General James McConville said that Russian hypersonic missiles were not a game changer because, “I have not seen them actually hit a target with that system.”1 U.S. Northern Command Commander General Glen VanHerck has said Russia has “challenges” regarding accuracy of its hypersonic missiles. He added that Russian missiles were still “on par” with U.S. missiles. This is apparently a reference to capabilities that Russian missiles have but U.S. missiles do not—supersonic and hypersonic speed, very long range, dual capability, and, in many cases, antiship capability (until recently when the United States began to introduce longer-range antiship missiles). These are important characteristics that don’t play much of a role in Russia’s war with Ukraine but which would be much more important in a war against NATO or against the United States and its Pacific allies.

In the most recent war between Armenia and Azerbaijan, Armenia used the Russian-supplied Iskander-E. Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan stated that 90 percent of the Iskander missiles “didn’t explode, or maybe 10 percent of them exploded,” although he later backed away from this statement. The problem was probably not mainly duds but rather accuracy. The Russian motive for attacking his claim is obvious. Russia wants to scare the West and sell Iskander missiles. While the Russian version of the Iskander is more accurate, it is likely that Russian claims about the Iskander-M’s accuracy are also exaggerated. Pashinyan’s initial statement may have reflected the poor accuracy of the Iskander-E, which is reported to have a CEP of 30 to 70 meters.

Noted Russian journalist Pavel Felgenhauer observed, “The Iskander as well as other Russian non-strategic missiles can be truly effective only with a nuclear warhead—apparently the way it is intended to primarily be used in any peer-to-peer conflict.” While Russian technical inferiority also plays a role, Mr. Felgenhauer is likely correct.

Because of shortages of modern missiles, in June, Russia began using older Kh-22 (NATO named: AS-4) missiles. The British Defense Ministry stated, “These 5.5 tonne missiles were primarily designed to destroy aircraft carriers using a nuclear warhead. When employed in a ground-attack role with a conventional warhead they are highly inaccurate and can therefore cause significant collateral damage and civilian casualties.”

Russia’s Dual-Use Threat

Assuming Russia does not use nuclear weapons against Ukraine (not a given), the poor performance of Russian missiles is good news. Presumably, it will fix the accuracy problems, but that will take time, as will rebuilding the inventory. This gives the United States more time to upgrade its forces for deterrence and potential conflict with Russia or China.

However, Russian missiles are not just conventional like U.S. cruise missiles, but rather dual-capable. The 2018 Nuclear Posture Review report confirmed that Russia “is also building a large, diverse, and modern set of non-strategic systems that are dual-capable (may be armed with nuclear or conventional weapons).” Dave Johnson, a staff officer in the NATO International Staff Defense Policy and Planning Division, observed that in regard to Russian precision strike weapons systems “all . . . are dual-capable or have nuclear analogs.” The distinction between conventional missiles and dual-capable missiles is very important.

The nuclear versions presumably will suffer from the same reliability and quality control problems as their conventional versions have demonstrated in the war against Ukraine. However, the accuracy and fusing problems will probably have little or no effect on the nuclear versions. While higher accuracy is always better than lower accuracy, for most targets, strikes with nuclear weapons do not require precision and accuracy or even near precision and accuracy. This is largely true even with low-yield nuclear weapons. The yield difference between conventional and low-yield nuclear weapons is enormous, and at very low yields the prompt radiation effects of nuclear explosions are often more important than blast. Furthermore, the Russian fusing problem resulting in duds will not likely affect the nuclear versions because they are products of different design bureaus with different design criteria and fusing is also generally different. For example, the “fallout free” height of burst is something that applies only to nuclear weapons. Direct ground impact will often be avoided to limit collateral damage. It should be noted that the only U.S. nuclear-armed cruise missile, the AGM-86B, is 40 years old, pre-stealth, pre-precision/near-precision accuracy, and has seriously eroded reliability—and this will be the case for almost a decade to come.

Except for Russia’s Kh-101 strategic air-launched cruise missile, all the missiles mentioned by Deputy Prime Minister Borisov have a primary or secondary antiship role. In the 2014 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russia seized most of the Ukrainian Navy. At the start of the 2022 war, Ukraine sank its only frigate to prevent Russia from seizing it. While the Russians used antiship missiles against land targets, they apparently did not use them for antiship attacks. However, because the missiles have terminal sensors for antiship use, the accuracy problems demonstrated in Russian land attacks probably would not apply against a ship target.

For a variety of reasons, the lessons the Russians learn from Ukraine may be very different from what the West learns. (Russian lessons from Syria, constantly mentioned, seem to ignore that Syria was a low-intensity conflict). As a result of their combat experience in Ukraine, some in the Russian military will likely argue for a further increase in nuclear capability and reliance. Indeed, increased emphasis on tactical nuclear weapons is being urged on Russian state television. Deputy Chief of the Russian National Security Council (and former President) Dmitri Medvedev has said that Russia would defend annexed Ukrainian territory (Donbas and Luhansk) with “strategic nuclear weapons and weapons based on new principles could be used for such protection.”

Putin has demonstrated a willingness to launch massively destructive attacks, lives in a fantasy world in which he is fighting Nazis, and is playing general much in the way Hitler did in World War II. If he remains in power or is replaced by someone like him, the free world has a serious threat on its hands.

1. Sean D. Naylor, “Russia’s Hypersonic Missiles Are Not ‘Game Changing,’ says U.S. Army Chief of Staff,” Yahoo News, 14 January 2020, news.yahoo.com/russias-hypersonic-missiles-are-not-game-changing-says-army-chief-of-staff-231032723.htm.