China and Russia are developing conventional and nuclear-armed hypersonic glide vehicle (HGV) and hypersonic cruise missile (HCM) weapons that pose significant challenges to U.S. security.

In October 2020, the Russian frigate Admiral Gorshkov successfully test-launched a new-design hypersonic weapon, the Russian news agency Tass reported. Operating in the White Sea, the Admiral Gorshkov fired a Tsirkon missile that flew about 280 miles before striking a maritime target. The missile reached a speed greater than Mach 8 during a 4.5-minute flight.

China also “has tested hypersonic glide vehicles,” the 2019 Annual Report to Congress: Hypersonic Weapons noted. HGVs travel at velocities greater than Mach 5 and fly at lower altitudes than a ballistic missile. The report noted China’s August 2018 test of the Xingkong-2 (Starry Sky-2), “which it publicly described as a hypersonic waverider vehicle.” Vehicles that travel faster than sound generate shockwaves (the “sonic boom”); a waverider essentially surfs on the shockwave.

Other militaries are also pursuing hypervelocity weapons—in Australia, the European Union, and Japan—as well as the United States.

Fired from ground-based ballistic-missile launchers, ships, and aircraft, HGV/HCMs avoid air-defense sensors and fly below ballistic-missile sensors. As the Government Accountability Office (GAO) explains in a July 2020 report to Congress (Missile Defense: Assessment of Testing Approach Needed as Delays and Changes Persist):

- Hypersonic vehicles are capable of flight at speeds five times the speed of sound (Mach 5) or greater. . . .

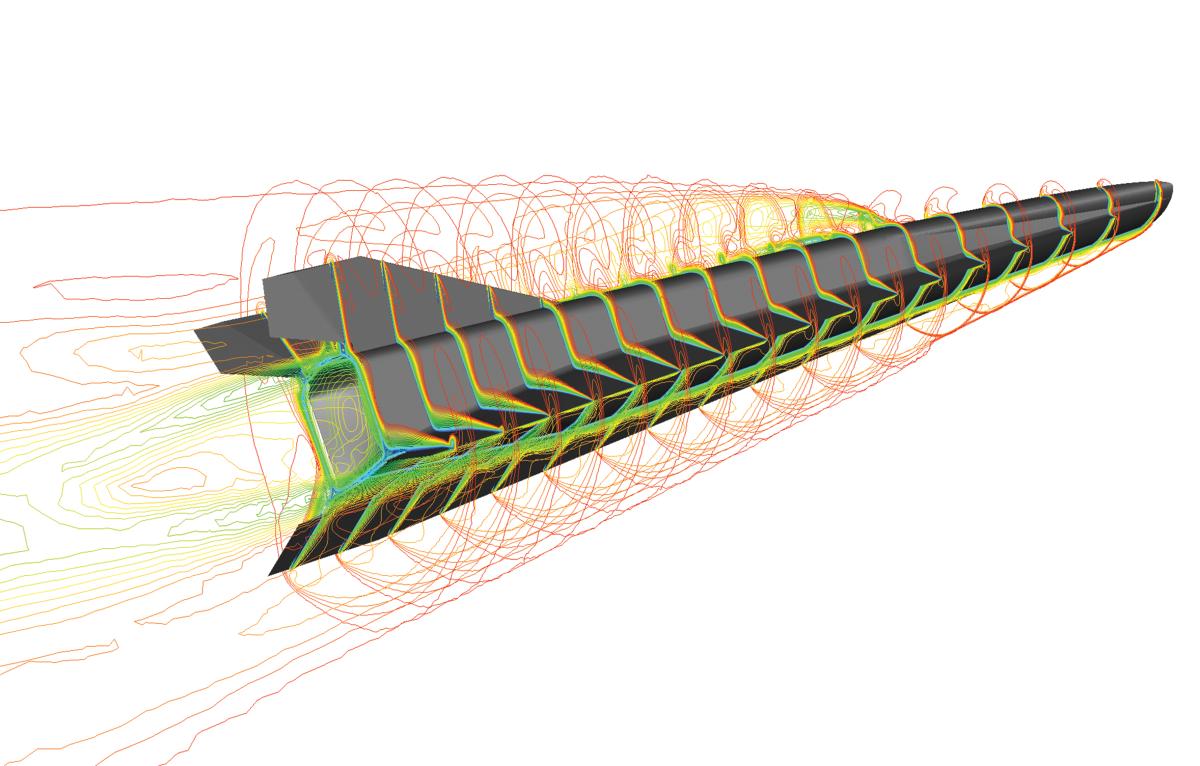

- HCMs resemble conventional cruise missiles, except that they employ a unique type of high-speed jet engine known as a scramjet. HCMs generally fly at lower altitudes [than] HGVs.

- HGVs resemble ballistic missiles in that they consist of a payload launched on a powerful rocket. Whereas a ballistic-missile payload will continue on a ballistic trajectory following the burnout of the rocket, an HGV payload is designed to glide on the upper edges of the atmosphere and is capable of maneuvering or changing direction on the way to its target. HGVs can provide several advantages over ballistic missiles by making tracking difficult and obscuring the intended target. Both of these features greatly complicate the objective of intercepting the HGV.

Michael D. Griffin, director of the Space Development Agency, told The New York Times Magazine these weapons “have the unprecedented ability to maneuver and then to strike almost any target in the world within a matter of minutes. Capable of traveling at more than 15 times the speed of sound,” he continued, at 12- to 50-mile trajectories, “hypersonic missiles arrive at their targets in a blinding, destructive flash, before any sonic booms or other meaningful warning. So far, there are no surefire defenses. Fast, effective, precise and unstoppable—these are rare but highly desired characteristics on the modern battlefield.”

This has sharpened and expanded U.S. missile-defense initiatives and programs. The GAO, for example, noted that the mission of the Missile Defense Agency (MDA) “has expanded beyond regional and homeland defense against ballistic missiles. Specifically, the Director of MDA is now the executive agent for defense against hypersonic glide vehicles.”

MDA’s Hypersonic and Ballistic Tracking Space Sensor capability, the first installment in an all-domain detect-control-engage sensor architecture, will provide a persistent, layered capability to track boosting ballistic missiles and HGVs. MDA is augmenting data on hypersonic threats provided by the intelligence community, collecting and analyzing data from various sensors participating in U.S. hypersonic flight testing.

And the Space Development Agency is responsible for installing a network of sensors in low-earth orbit that would track incoming hypersonic missiles.

— Scott C. Truver

Shipbuilding Update

Navy

Guided-Missile Destroyers

Frank E. Petersen Jr. (DDG-121) will

commission in 2021

John Basilone (DDG-122) keel laid

down January 2020

Daniel Inouye (DDG-118) will

commission in 2021

Lyndon B. Johnson (DDG-1002) will

transit to San Diego for combat systems installation ahead of commissioning

Littoral Combat Ships

USS Kansas City (LCS-22) commissioned on 20 June 2020

Minneapolis–St. Paul (LCS-21) will

commission in spring 2021

Cooperstown (LCS-23) delivered

in February 2020

Oakland (LCS-24) delivered in

January 2020

Nantucket (LCS-27) christened

December 2019

Nuclear-powered Aircraft Carriers

John F. Kennedy (CVN-79) christened

December 2019

Nuclear-powered Attack Submarines

Oregon (SSN-793) will commission

in spring 2021

Coast Guard

National Security Cutters

Stone (WMSL-758) delivered

November 2020

Offshore Patrol Cutters

Argus (WMSM-915) keel laid April 2020

Fast Response Cutters

USCGC Daniel Tarr (WPC-1136)

commissioned January 2020

USCGC Myrtle Hazard (WPC-1139)

commissioned May 2020

USCGC Edgar Culbertson (WPC-1137) commissioned June 2020

Harold Miller (WPC-1138)

christened July 2020

Oliver Henry (WPC-1140)

delivered July 2020

Charles Moulthrope (WPC-1141)

delivered October 2020

(Note: Coast Guard cutter information current as of 5 October 2020 Register of Cutters of the

U.S. Coast Guard. Navy information derived from navycommissionings.org and U.S. Navy sources.)