In the Sea Services, we often pride ourselves on being first—the first to crew a ship, the first to head a new department, or the first to lead a new command. This pioneering pleasure is not unique to the Navy or Marine Corps, although the services add some flair to it by embracing the term “plank owner” when describing members who break new ground.

Innovation is not the problem here. Instead, the problem arises when we allow being first in some given role to excuse doing due diligence in the execution of those duties. For junior officers, failures and missteps may be explained away under the premise of standing up something new. However, nothing is ever truly new. The common adage is that history does not repeat itself, but it often rhymes. Initiative can fail when junior officers ignore precedent they should have known.

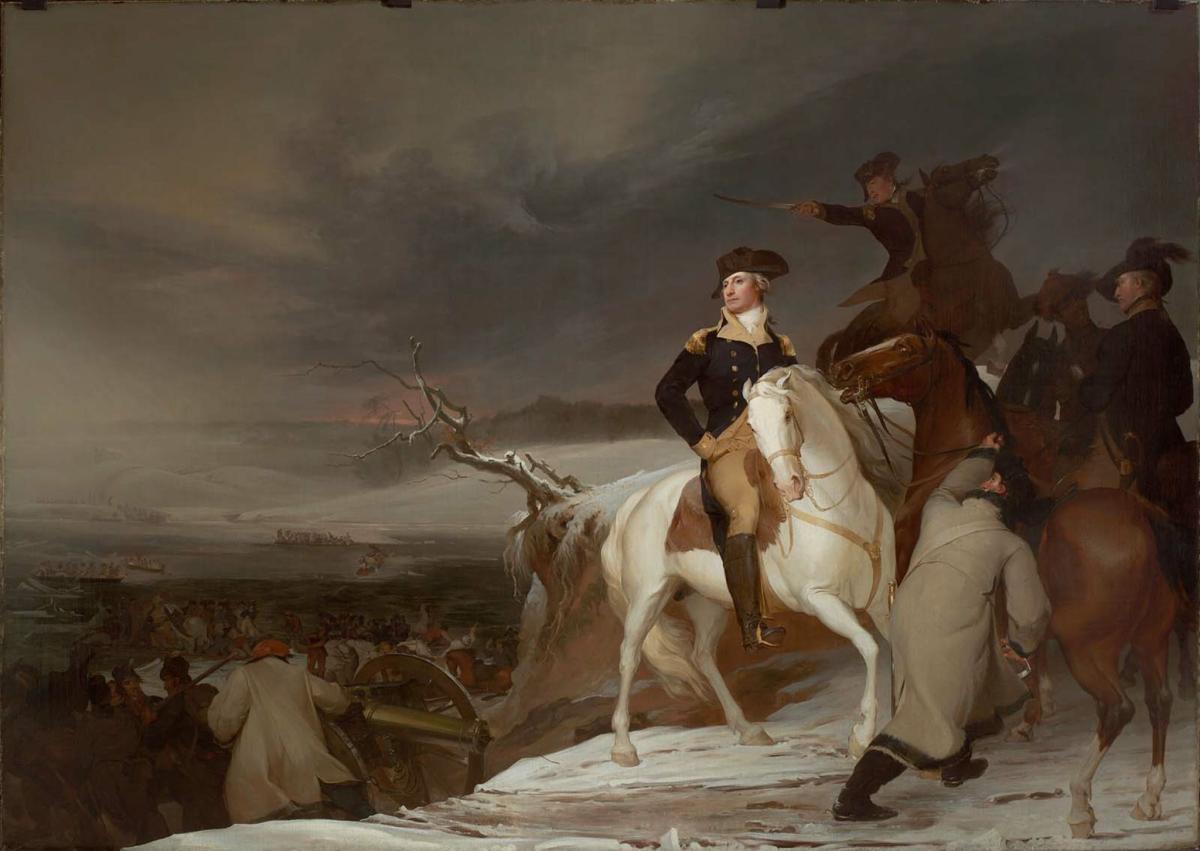

To demonstrate just how pervasive this attitude can be, and how much junior officers can learn from the past, consider how lessons about emotional control, dealing with subordinates, or even social media could easily be predicted by prior leaders. The emphasis here will be on one leader, the ultimate American plank owner—George Washington.

About Social Media

Social media underscores how old lessons are somehow new again for each generation. Specifically, in the annals of U.S. history, there is perhaps no more singularly wanton act of destruction than when Martha Washington burned correspondence with her husband during the Revolutionary War. More than just background about their relationship, what other historical pearls vanished that night? What could we have learned about the character of the first U.S. President?

Rather than thinking about what the National Archives lost, think about what junior officers might gain. Namely, some elements of one’s life are best left private. Martha preserved that confidentiality for her husband by destroying the letters after his death. Today, social media often exposes too much raw emotion and too many unfiltered thoughts to make them tenable. Arguments, doubts, and outbursts are recorded in real time without the filters of good judgment, the benefit of hindsight, or even the privacy of a handwritten letter.

That said, all officers harbor some doubts. They may want to shout so loud that paint peels from the walls, and everyone needs someone with whom to share things in confidence. After all, burdens are easier to bear when they are not carried alone, and the psychological value of this act—even when limited to discussion—cannot be overstated. The challenge becomes finding someone you can trust completely. Washington chose to share his concerns with a trusted partner rather than blast them through the Boston Gazette, but a confidant does not need to be a spouse. Family, colleagues, and mentors all serve as reasonable confidants. Whatever the relationship, there must be an individual to whom you can express those thoughts that concern you, yet which are not suitable for the hollowed pages of social media.

Find someone who would burn your letters.

About Emotional Control

By age 16, Washington knew almost by heart the “Rules of Civility and Decent Behavior in Company and Conversation.”1 Some rules seem stodgy or aristocratic, such as “shift not yourself in the sight of others nor gnaw on your fingernails.” Many would align with our modern grooming standards for military service. Some, however, have deeper meaning and purpose to the nature of an officer and servant leader, such as “If anyone come to speak to you while you are sitting, stand up though he be your inferior, and when you present seats, let it be to everyone according to his degree.” In essence, respect your subordinates and enable them without insult or self-flattery. Dozens more of the 110 rules have similarly modern leadership implications.

The concept of an officer and a gentleman never really had anything to do with ballroom dances or chivalry. A virtuous nature may improve your perception or standing in the view of others, but the real, practical value is in developing emotional control. Those same rules, if properly followed, can help a junior officer learn how to ensure good social or public behaviors to prevent misunderstandings. More important, you can learn to control your temper. There will be moments when professional relationships or even your career might be saved by taking a breath before shouting an impassioned thought.

Washington demonstrated the concept of perfect civility when facing leadership challenges from one of his subordinates, Charles Lee. In 1776, amid the many troubles the Continental Army faced, the American people had real reason to doubt Washington’s leadership. Now, in this context, imagine accidentally opening a letter or e-mail from a subordinate who is not only openly competing for your job, but actively refers to your leadership as “that fatal indecision of mind which in war is a much greater disqualification than stupidity or even want of personal courage.” Lee allowed his ego and ambition to undermine his tactical brilliance. In response, Washington could have tried to cauterize the insubordination by stripping Lee of command. That likely would have caused more problems without solving any. Washington also could have lost or burned the letter without saying a word. Instead, he passed the correspondence to its intended recipient, Joseph Reed, with a letter of his own explaining the accident and wishing well to him.

There is an honesty and civility evident in Washington’s decision. Transparency is sometimes the best course of action, especially when there is reason to doubt your intent, because lies and obfuscation will only make matters worse.

Lee took the opposite approach. After the Battle of Monmouth, and the mythologized shouting match following his actions there, Lee demanded satisfaction.2 He crossed the line. The soon-to-be-former general wrote insolent responses to George Washington, and rather than emulate his famous emotional control, Lee demanded a court-martial. Washington obliged. Lee allowed his ego to put him into a position that eventually led to dismissal from the Army.

Do not let your ego dictate your actions.

About the Harsh Judgments of History

Junior officers already recognize the challenge of adopting a zero-defect mentality in military service. However, the problem with a zero-defect culture is not the refusal to accept errors, but the unwillingness to permit change. Failure should not be the automatic end of a career; however, failure without change demonstrates an unwillingness to grow. That should be the disqualifying factor.

Washington has one unquestionably abhorrent shortcoming—he owned slaves. He issued orders that black soldiers were not to be enlisted into the Army. He explicitly said people should be denied the opportunity to serve, not because of their fitness for duty or devotion to country, but because of the color of their skin. Can you imagine a commanding officer today refusing to serve with sailors because they happen to be a racial minority? Even the best-case answer to that question involves being stripped of command.

So, the most important Founding Father did not meet the modern-day zero-defect standard. What does that imply about the man or about our modern standard? For starters, change after failure should matter. Washington slowly changed his opinion about slavery until he began supporting abolition. He wrote in a letter dated 1786: “I can only say that there is not a man living who wishes more sincerely than I do, to see a plan adopted for the abolition of it.” The lesson? Learn that you can be wrong. You can change your mind over time. The cultural answer must not only be about allowing failure or disagreement among servicemembers. The answer must also permit the possibility that people can change, or the whole point is lost.

But history will be a harsh judge. Scholars, Monday-morning quarterbacks, and even nonjudicial punishment hearings have a benefit of hindsight or context that may allow them to use a different measure to evaluate the actions in question. Context will not excuse your actions, nor protect you from repercussions.

Another lesson is that you may never know the future moral code against which your actions will be judged. However, you can know the moral code against which you weigh your decisions. Find a moral center, the piece of you that remains core to all your actions. Understand what it means for you. Learn about it—challenge it—by asking yourself hard questions. What would you be willing to sacrifice? What lines would you cross and when would you cross them? Understand yourself so that service members can trust you to do the right thing, even when the “right thing” is more question than answer. As Washington could have quoted, “Labor to keep alive in your breast that little spark of celestial fire called conscience.”3

Determine your actions by a moral code rather than their context.

About Factionalism

Factionalism has other names, and today, we would likely refer to it as partisanship. However, the underlying point remains the same. People ignore faults in allies or virtues in adversaries so long as they are on the same or opposing sides, respectively. Partisan politics can force service members into debates that, at best, run afoul of Department of Defense policy, and, at worst, create a loss of trust and confidence in military leaders. Partisan squabbles prevent unity and complicate discussion or compromise when one American sees another as an enemy because of a political party.

Washington knew the threat partisanship posed to national interests. He all but predicted the inevitable problems when people put party before country. During his farewell address in 1796, Washington wrote at length about the problems of political infights, retribution, the dangers of despotism, and how partisanship can open the door to foreign influence. His speech could be considered a masterful demonstration of how 45 years in public service can make political squabbles seem pointless. Its wisdom could not be contained to 144 or 288 characters, although the text might benefit from a bit more brevity—the reduction of which is a good exercise for any junior officer. In short, allowing Americans to be divided into factions undercuts the potential of our country. We are all Americans serving the same country and defending the same Constitution.

We are one team in one fight.

Be a Plank Owner—Don’t Think Like One

Military service changes so often that you are likely to be the first in some position or building some new program. You will own a plank of something. Do not let building something new be the reason for your missteps or excuse you from learning the lessons of history. If you can learn something about social media from George and Martha Washington, there might be other lessons from reading before you are left to learn the hard way. General James Mattis summarized the point well when he wrote:

Thanks to my reading, I have never been caught flat-footed by any situation, never at a loss for how any problem has been addressed (successfully or unsuccessfully) before. It doesn’t give me all the answers, but it lights what is often a dark path ahead. . . . “Winging it” and filling body bags as we sort out what works reminds us of the moral dictates and the cost of incompetence in our profession.4

Be proud of the efforts in becoming a plank owner, but do not think you are truly the first to do anything. Look to those who came before you and learn the lessons they have to offer. Do not stumble through the dark because you were too proud to turn on the light.

1. George Washington, “Washington's Rules of Civility and Decent Behavior in Company and Conversation: A Paper Found Among the Early Writings of George Washington,” Copied from the Original with Literal Exactness, W. H. Morrison, 1888.

2. Mark Edward Lender and Garry Wheeler Stone, Fatal Sunday: George Washington, the Monmouth Campaign, and the Politics of Battle 54 (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2016).

3. The final entry on the list, rule number 110. Washington, “Washington's Rules of Civility and Decent Behavior in Company and Conversation.”

4. Jill Russell, “With Rifle and Bibliography: General Mattis on Professional Reading, Strife Blog, 7 May 2013. These two passages are distinct entries from correspondence General Mattis sent a colleague in answer to those officers too busy to read.