Attention to award!

For extraordinary courage and disregard for his own personal safety during the attack on the Fleet in Pearl Harbor . . . Despite enemy strafing and bombing, and in the face of a serious fire . . . [Miller] manned and operated a machine gun directed at enemy attacking aircraft.

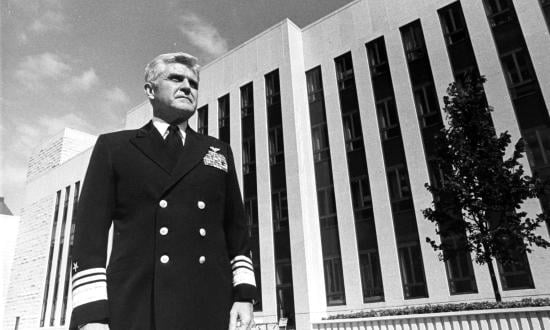

With these words, on an overcast spring morning in 1942, Admiral Chester Nimitz awarded Messman Third Class Doris “Dori” Miller the Navy Cross. The gallantry Miller displayed during the attack on Pearl Harbor is legendary. His heroism has been captured in books and on the silver screen. But the simple act of Admiral Nimitz, in the frenetic days between two of the most critical naval battles of World War II, is a lesson in leadership that should not be overlooked.

Just days before Nimitz and Miller shared this moment, significant losses fighting a practiced and determined Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) during the Battle of the Coral Sea had severely blunted the spear of the U.S. Navy; and planning for the Midway campaign, a mere week later, had entered the final, breakneck stages.

Despite these critically important battles—the loss of which would have had existential implications for Allied forces—Nimitz made time to honor Dori Miller. This is the first Five-Star Leadership Lesson: Sailors first.

Five-Star Leadership Lesson 1: Sailors First

An awards ceremony could have been delegated to a subordinate commander, but Nimitz understood the importance of putting his sailors first. Without the sailors of the Pacific Fleet, defeating the Japanese Empire would have been impossible.

The mantra of putting sailors first is as old as the Navy itself. This is what John Paul Jones had in mind when he said, “Men mean more than guns in the rating of a ship.”

In today’s Navy, newly commissioned officers can get be overwhelmed by the number of tasks to complete. It may be easier to put off small things such as promotions or reenlistments, but great leaders understand the value of putting people first. Before commanders can achieve mission success, they first must tend to the “care and feeding” of their personnel. Take the time to build a strong team, and then set out to accomplish the mission.

Nimitz did not believe naval leaders should place individual happiness above mission accomplishment. That would be unsustainable in any context, and especially foolhardy at the height of World War II. But Nimitz invested time in the service members under his command and made himself available to meet with every commanding officer that pulled into Pearl Harbor; believing genuine relationships yielded better results. 1

Nimitz showed that a key element to mission success is to put sailors first. “A leader who conquered any personal urge to drive,” he “achieved his ends more by persuasion and inspiration to the men under his command.”2

Five-Star Leadership Lessons 2: Set Audacious Goals

Standing in front of Dori Miller, Nimitz wore his dress whites, but the next day he wore waders, sloshing around the bottom of a slowly draining dry dock that held the wounded USS Yorktown (CV-5).

The Yorktown had just limped back to Pearl Harbor after the Battle of Coral Sea. She paused briefly as she entered the harbor to render honors to the sunken hulks still resting on the sea floor since the “day of infamy,” 7 December1941. The Yorktown’s initial damage report left no doubt—repair attempts would be a herculean task:

A 551-pound bomb had plunged through the flight deck . . . and penetrated 50 feet into the ship before exploding. Six compartments were destroyed, as were the lighting systems on three decks and across 24 frames. The gears controlling Number 2 elevator were damaged. She had lost her radar and refrigeration systems. Near misses by eight bombs had opened seams in her hull from frames 100 to 130 and ruptured the fuel-oil compartments. Rear Admiral Aubrey Fitch, aboard the damaged carrier, estimated that repairing her would take 90 days.3

But Nimitz did not have 90 days. If intelligence reports were correct, the Japanese Fleet would make its next attack just eight days later. After showing up to the dry dock for a personal inspection, he gave a blunt order: “We must have this ship back in three days.”4

Setting aggressive goals is the second example of five-star leadership. Great organizations accomplish more than others—or even themselves—think possible because they set monumental goals.

In their book Built to Last, Jim Collins and Jerry Porras discovered that the highest achieving, visionary organizations always set “big, hairy, audacious goals,” or BHAG (pronounced BEE-hag). “A true BHAG,” they explain, “is clear and compelling, serves as a unifying focal point of effort, and acts as a clear catalyst for team spirit.”

Naval history is full of leaders who used the BHAG concept to aim high and exceed all expectations. When Admiral Grace Hopper, commissioned in 1943, set the goal of creating a computer programming style using English words instead of obscure symbols, few believed it was possible. Yet within just three years, “Amazing Grace,” as she became known, had invented a computer programming style that laid the foundation for COBAL, the “most ubiquitous” programming style used in business for a generation.5

Admiral Hyman Rickover also set a BHAG when he resolved to create an entire fleet of nuclear-powered submarines. His superiors initially were so opposed to the idea, they recalled him to an administrative job and assigned him a vacated ladies' rest room as an office. But Rickover was determined. In 1947 he appealed directly to Nimitz, then the Chief of Naval Operations. Nimitz immediately saw the merit in Rickover’s plan and paved the way for the project.6 A new era began in 1955 when the commanding officer of the USS Nautilus (SSN-571) sent the historic message: “Underway on nuclear power.” We now remember Rickover as the father of the nuclear navy.

In both examples, leaders set a target that seemed out of reach, but they homed in with “monomaniacal focus . . . to defy the probabilities and ultimately achieve their BHAG.”7

Five-Star Leadership Lessons 3: Create an Environment for Success

Nimitz understood high expectations alone would not be sufficient. He also needed to create an environment for his people to thrive—lesson three. He did so through three steps.

First, he saw for himself. Nimitz did not rely on damage reports; he went into the dry dock, talked to the experts, and personally surveyed the damage. This is referred to as “leadership by walking around.” Five-Star Leaders know if you are going to lead, you must be where it counts. Get your hands dirty and see ground truth.

Next, he cleared away the clutter so his team could focus on the core mission. For the Yorktown, Nimitz waived a regulation that would have required an additional three days to remove fuel and ammunition. In peacetime, leaders should never relax safety requirements, but they should always be on the lookout for unnecessary administrative burdens that bog down sailors. Granting their teams the freedom of action to decide and execute the primary goal is one of the most important things a leader can do.

Last, creating an environment for success also means allocating the proper resources. As soon as Nimitz gave his order to return the Yorktown to service in just 72-hours, more than 1,300 shipyard workers streamed into the dry dock for repairs. The massive effort required the Navy to convince the local electric company to divert extra power to the shipyard, causing rolling blackouts in Honolulu.8

Setting high goals without understanding the situation on the ground, removing extraneous tasking, and allocating the proper resources is a guaranteed way to fail. “Leadership,” Nimitz said, “consists of picking good men and helping them do their best.” Challenge your sailors with audacious goals and then create an environment for them to succeed, and your team will exceed your greatest expectations.

Five-Star Leadership Lesson 4: Trust Your People

On 28 May 1942, the shipyard workers accomplished Nimitz’s goal as the Yorktown was slowly towed out of Dry Dock One. She still had dozens of employees on board and they ignored lower priority repairs, but on 30 May preparations were complete for her to sail for the decisive battle that would begin in just five days.

So, how did the future fleet admiral know where to deploy his newly repaired carrier to prepare for the imminent attack? He trusted his people.

From a basement room nicknamed “The Dungeon,” cryptologists under the leadership of Commander Joseph Rochefort had deciphered much of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) code. They knew when and how the next attack would take place, but they could not be sure where. In the intercepted transmissions, the Japanese only referred to their next target as “AF.” There were several U.S. outposts in the Pacific that could have been AF, but the stakes were too high to guess. Nimitz needed to be sure.

The solution came through misinformation. Transmitting what appeared to be a simple habitability update, Midway reported to Headquarters in Hawaii that the island was dangerously low on drinking water. Rochefort hoped the Japanese would intercept the transmission and report to Tokyo. The ploy worked. A Japanese listening station reported AF was out of drinking water, and Nimitz had the confirmation he needed.9

But it was still a risk. If Americans had broken the IJN’s code, the U.S. code could also be compromised, allowing the IJN to use misdirection of their own. To make matters worse, the intelligence community in Washington strongly disagreed with Rochefort’s assessment of Midway as the target. Nimitz could not be sure, but he trusted his people—lesson number four.

Nimitz understood the value of trust in leadership. “Some of the best advice I’ve had,” he once reflected, “comes from junior officers and enlisted men.” Leaders should constantly solicit the recommendations of junior personnel. Often, they are the ones who know what the real problems are and how to solve them.

The Navy creates a paradoxical relationship between the chief petty officer and the ensign. Even though ensigns are senior to chiefs, it is the chief who holds the real-world experience. Junior officers (JOs) who master this relationship and learn to trust their chief can gain access to decades of experience that will make them better officers and leaders. JOs who lead with arrogance and fail to trust those junior to them, are doomed to frustration and stunted professional development.

But trust is a two-way street; leaders must also inspire the trust of their followers. “Good leaders,” as Colin Powell said, “are people who are trusted by followers. And good leaders can take organizations past what the science of management says is possible.”

To earn the trust of their sailors, junior leaders must become technically competent and tactically proficient in their new profession. Besides attaining qualifications and gaining the experience necessary to stand a proper watch, they also must study the art of leadership. A JO’s billet will change with each tour, but they will take charge of increasingly complex situations and manage increasingly larger units throughout their career. Developing leadership skills is a critical element of success for a junior officer.

Five-Star Leadership Lesson 5: Be Ready to Fight

All the pieces were falling into place. Nimitz would have Yorktown available to fight alongside USS Enterprise (CV-6) and USS Hornet (CV-12). He knew the date and location of the battle, thanks to Rochefort’s code breakers. But Nimitz still had a choice to make: fight or hold his force in reserve for another day.

Nimitz, a man known for being “aggressive in war [but] without hate,” committed his forces despite being severely outnumbered. The three American flattops were joined by just 17 destroyers, eight cruisers, and a dozen submarines. The Japanese force, however, boasted four fleet carriers, two light carriers, 65 destroyers, 22 cruisers, 11 battleships, and more than 15 submarines.10 Engaging the IJN fleet was a bold move for Nimitz, who was described as “audacious while never failing to weigh the risks.”11

Yorktown still had maintenance crews on board conducting repairs when she entered battle, but air wings from the three carriers combined to repel the Japanese attack in what military historian John Keegan called, “the most stunning and decisive blow in the history of naval warfare.”

“When the sun set on 4 June 1942, four Japanese Fleet carriers were at the bottom of the Pacific, or soon to be there, and with them went the Imperial Japanese naval dominance.”12 So significant were the Japanese losses, that they would never again control the Pacific Ocean. The war waged on for three more years, but the defeat at Midway set the course to the ultimate defeat of Tokyo.

No one can know when the call of history will be as great as it was in the Pacific during World War II, but one thing is sure, our Navy will be called again. When that day comes, we must be ready. Ensure you and your sailors are ready to fight. Make sure you are mentally prepared and your sailors have the resilience to endure the hardships of battle. Admiral John Richardson, former Chief of Naval Operations, has said “toughness” is a core attribute to maintain maritime superiority. Embody that toughness daily and demand it of your sailors.

* * *

The frenzied days between Coral Sea and Midway were fraught with danger. Nimitz understood the stakes well, yet he made time to pause, put on his dress uniform and honor the heroic actions of a junior petty officer. He put his sailors first and relied on fundamental leadership principles to lead the United States to victory at Midway. Today, we can apply the same principles as we strive to become Five-Star Leaders.

To the junior officers: apply the principles Nimitz used in the days of June 1942. Do not be afraid to lead and inspire your sailors. Lead from your heart and your mind. Sailors want and deserve great leaders. It's your job to become one.

1. Samuel Elliot Morison, The Two-Ocean War: A Short History of the United States Navy in the Second World War (Little, Brown & Co., 1963).

2. Edwin Palmer Hoyt, How They Won the War in the Pacific: Nimitz and his Admirals (Lyons Press, 2011).

3. Dwight J. Zimmerman, “Battle of Midway: Repairing the Yorktown After the Battle of Coral Sea,” Defense Media Network, 26 May 2012.

4. Zimmerman, “Battle of Midway.”

5. Kurt W. Beyer, Grace Hopper and the Invention of the Information Age (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2009).

6. Robert Walace, “A Deluge of Honors for an Exasperating Admiral,” Time Magazine, 8 September 1958.

7. Jim Collins and Jerry Porras, Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies, (HarperBusiness, 1994).

8. Zimmerman, “Battle of Midway.”

9. Elliot Carlson, Joe Rochefort’s War: The Odyssey of the Codebreaker Who Outwitted Yamamoto at Midway (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press; Reprint edition, 2013).

1.0 Dwight J. Zimmerman, “Midway 1942: When the Odds Were Against Us,” Defense Media Network, 4 June 2015.

11. E. B. Potter, Nimitz (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2008).

12. Dwight J. Zimmerman, “Battle of Midway: Black Shoe Admirals in a Brown Shoe Battle” Defense Media Network, 4 June 2012.