When a ship returns from deployment beaten by the ravages of sea, necessary maintenance occurs, systems are updated, and the vessel once again is made battle worthy before it finishes its maintenance phase. Realizing that something old, worn, and outdated needs a refit does not detract from its previous accomplishments, but instead signifies that the hull of a successful platform from the past can be crafted into something even better for the future. Contrast this with Navy cyber, which, while it has accomplished much, has remained stagnant, even as the cyber policies of other services have shifted at the same rate as technological innovation. Only with a refit can Navy cyber meet future challenges.

More than 15 years before cyber was introduced as the fifth domain of warfare in 2011, the Navy set the standard for investment in this field by funding new technologies such as The Onion Router (TOR), a browser that allows anonymous internet communication.1 In 2018, U.S. Cyber Command (CyberCom) was elevated to a unified combatant command and the roles of the services in support of national cyber objectives were codified.2 CyberCom, along with the National Security Agency (NSA) and service component support, took the lead in securing the newest domain of warfare. That year, CyberCom and NSA acknowledged conducting more than 2,000 cyber operations supporting election security, finally giving the public a glimpse into the capabilities and necessity of a strong, equipped, and operationally ready cyber force.3

In the Navy, cryptologic warfare officers (CWOs), cyber warfare engineers (CWEs), cryptologic technicians networks (CTNs), information systems technicians (ITs), and other supporting rates are quietly playing a pivotal role in the constant digital battle being waged in neutral and enemy networks around the globe.4 Although these cyber professionals produce stunning results behind thick, sensitive compartmented information facility (SCIF) doors, the Navy continues to lag the Air Force, Army, and Marine Corps in policies to optimize cyberwarfare success and boost retention while promoting cyber warrior career longevity. While testifying before Congress in May 2021, Army General Paul Nakasone, commander of CyberCom and director of NSA, acknowledged the long-standing cyber retention problems within the Department of Defense (DoD) that have led to trouble maintaining operational readiness.5 Well-trained talent continues to flow from active-duty assignments into civilian positions at CyberCom, NSA, or the corporate world.

There is no silver bullet to correct cyber retention deficiencies. Only a methodical, layered approach will help the Navy regain its footing as a service dedicated to cyber. A Navy cyber refit is long overdue, and four primary areas will have immediate effect on mission success: pay, training, leadership development, and technical longevity.

The Pay Divide

General Nakasone does not dispute that the enlisted cyber force can make multiples of their current salaries in the private sector.6 Although research suggests that pay has only a moderate correlation to job satisfaction and retention, data also indicates that a larger divide between current pay and potential pay will cause it to become a more important factor in career decisions.7 Pay likely plays a greater role for Navy cyber warriors because of the large gap between their current pay and the pay they could be earning in another service or outside DoD.

Although the current DoD cap for reenlistment bonuses is $180,000, highly trained Navy interactive on-net operators (IONs) receive just half the approved maximum for a Zone C (between 10 and 12 years of service) reenlistment.8 Ninety-thousand dollars for signing up for a six-year stint is no small amount, but it fails to persuade a majority of the most valuable cyber experts to stick around for the long haul. With an established mechanism to reward cyber professionals, and plenty of room for expansion, the reenlistment bonus has morphed into a missed opportunity to improve retention.

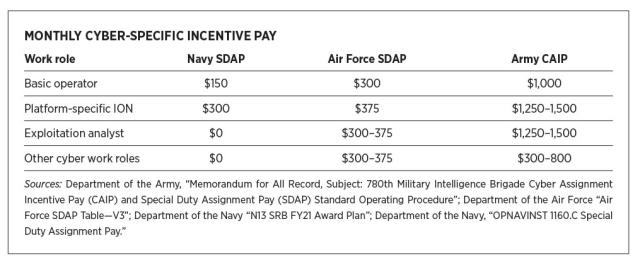

Another area of compensation the Navy neglects compared to other services is assignment incentive pay (AIP). The Navy’s special duty assignment pay (SDAP) for basic IONs is half that of the Air Force and only 15 percent of what the Army offers. Even the most highly trained Navy IONs receive 25 percent less than their Air Force counterparts and only 20 percent of the amount provided by the Army.9 Navy cyber warriors know not only that they can make multiples of their current salary outside the Navy, but also that they receive less incentive pay than their coworkers wearing different service uniforms, which demoralizes sailors by leaving them feeling undervalued, underappreciated, and underpaid. To sailors, these numbers suggest senior leaders’ failure to prioritize improving the cyber force writ large.

The DoD maximum for AIP compensation is $3,000 per month, meaning the Navy has the authority to award larger sums.10 Instead of remaining last on a list for compensation, Navy leaders can send an unequivocal message to the force that cyber skills are valued by raising the SDAP to, at minimum, match the Army’s cyber assignment incentive pay (CAIP).

The Navy also fails to address the lack of incentive pay for critical supporting cyber work roles, such as the exploitation analyst (EA), a position plagued by retention challenges similar to those seen by IONs.11 Both the Air Force and Army anticipated these hurdles and leaned forward to open the coffers for EAs and many other cyber-related work roles.12 EAs in the Army can receive AIP equivalent to their ION counterparts, but these positions receive nothing in the Navy. As with IONs, the Navy must provide competitive compensation or risk losing its best cyber capabilities—its people.

World-Class Training Should Not Hurt

The training pipeline for IONs and EAs is long and arduous, beginning at CTN A-school with a 22 percent attrition rate.13 They also must overcome a post–accession level training pipeline with an attrition rate as high as 50 percent.14 IONs require approximately three years from initial training until they can operate solo, already halfway through an enlistment.15 With NSA controlling this training and allocating only a certain number of slots to services per year, the process often is extended.16 The timeline for EAs, the navigators for cyber operations, is similar, requiring nearly three years to reach the minimum qualification level to oversee various cyber operations.

To decrease attrition within these demanding pipelines, sailors and their chains of command are required to sign an agreement with the training authority acknowledging that trainees are full-time students and are not to be unnecessarily burdened by their service components.

Not only is the training regimen challenging, but so is advancement. Years of remaining in a training status drastically hampers promotion progress. Unqualified CTNs working through the ION or EA pipeline consistently receive evaluations below fully qualified CTNs in positions requiring only a few months of training, which can have serious career implications if ION or EA trainees are second- or third-term sailors attempting to “break out” from their peers with strong evaluations. Competitive disadvantages such as these can have harmful effects on trainees’ perceptions of how the Navy views the development of their craft. Much of the problem stems from the Navy’s antiquated binary distinction of qualified versus unqualified for evaluation assessments.

The Navy must identify policy to reward cyber trainees enrolled in lengthy pipelines without hampering career progression. Automatic advancement on qualification, separate billet categories to allow for flexibility for promotion recommendations, or basing evaluation rankings on grades earned through courses of study could have immediate positive effects within the force.

A culture shift must occur to acknowledge their dedication, especially in positions considered key for national and combatant command objectives. Steps must be taken to ensure the most highly sought cyber personnel are not adversely affected for undertaking one of the toughest pipelines in DoD. If not, the Navy risks pushing gifted sailors away from these career paths, or toward exiting service after only one or two tours, thereby continuing to hurt an already undermanned field.

Tactical Leaders on the Cyber Front Lines

Cryptologic warfare officers (CWOs) are responsible for many facets of information operations, such as cryptology, signals intelligence, command and control, cyber warfare, space systems, and electronic warfare. CWO is the primary designator overseeing cyber-related missions and operations, with minimal involvement from CWEs, as the latter primarily are leveraged as developers and engineers for cryptologic and cyber-related capabilities. In addition, the Navy established its cyber warrant program as a retention tool to meet the growing demand for the ION work role.17

CWOs learn broad, rudimentary fundamentals during initial training, but in-depth expertise comes from on-the-job training. A rigidly defined career path exists as a template for promotion, which typically does not allow more than one tour per field, and ensures experience is gained in multiple areas under the CWO purview but precludes the development of deep expertise in individual concentrations. Careers exist in which this type of leadership training structure is successful. The technically demanding, fast-paced cyber domain, in which change is measured in weeks rather than months, is not one of them.18

The Air Force, Army, and Marine Corps acknowledged the necessity of technically astute leaders in cyber warfare by creating cyber operations officer (COO) designators.19 These COOs have the opportunity for multiple tours across the cyber field while receiving training and experience to lead the fastest-growing warfare domain.

Each of these branches has extensive training for COOs: Army and Marine Corps COOs train for nine months. Air Force COOs receive 23 weeks of cyber education and can attend the equivalent of A-school for CTNs, which gives leaders the same building blocks as their enlisted counterparts. Along with specialized training, the Air Force and Army recognized the value of tactically trained leaders by allowing members of their officer cadre to become ION and EA qualified.20 These decisions have fostered professional growth while developing leaders trusted for their experience and not just their rank.

Furthermore, the required training pipeline for officers in cyber billets once was extensive, but the Navy now offers no training for officers en route to their permanent assignment. Combined with the lack of service-level training for Navy CWOs performing the duties of COOs, this shortfall leaves Navy officers ill-equipped to lead the technical sailors and missions under their charge. A shortage of technically savvy leaders is one of the Navy’s many cyber challenges.

Just as the Marine Corps does with its COOs, Navy collaboration with the Army Cyber School can shore up this deficiency until the Navy develops its own COO designator and associated training curriculum. The need has never been greater, and the solution has never been more evident: Create a Navy COO to be the bedrock of leadership for the future of Navy cyber.

Stay Technical, Stay Navy

A 2019 RAND study concluded that the top reason military cyber professionals leave the service is their desire to keep doing technical work longer in their careers.21 The Navy must make this possible if it wants to improve retention.

The reality for sailors is that with advancement comes administrative responsibilities, which has negative implications for those who are cyber-focused. As General Nakasone noted, manning challenges already impose more operational duties on the cyber workforce, leaving less time for Navy cyber professionals to balance administrative responsibilities. Sailors face a conundrum. Not making rank keeps them farther from the pay they could earn in another service or the civilian market but promotion hinders them from maintaining their technical prowess.

Instead of allowing this dilemma to perpetuate, the Navy must reconsider the responsibilities levied on its cyber professionals. The most successful IONs and EAs already are leaders in an operational capacity, including performing burdensome administrative functions to meet the strict requirements of a sensitive, technically demanding field.

The Navy must acknowledge the blending of operational and administrative functions within the cyber field and remove the burden of Navy-specific administrative duties (i.e., collateral duties). Doing so will allow sailors to receive recognition for the technical and administrative functions they serve, so they can be competitive at ranking boards without a reduction of operational output and remain in technical positions longer—improving retention within all work roles.

The argument for improving Navy cyber is not new, but the necessity of a refit has never been more apparent. Other branches have allocated substantial resources to make cyber a priority. If the Navy desires a stake in the cyber fight, it must make a full commitment. General Nakasone once said, “Near-peer competitors are posturing themselves, and threats to the United States’ global advantage are growing—nowhere is this challenge more manifest than in cyberspace.”22 The Navy cannot wait to regain the cyber advantage necessary to meet enemies across the cyber continuum. It is time to update policies and create an environment conducive to full careers instead of single tours.

1. Department of Defense, DoD Strategy for Operating in Cyberspace (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 2001); Lily Hay Newman, “The CIA Sets Up Shop on TOR, the Anonymous Internet,” Wired, 7 May 2019.

2. U.S. Cyber Command, “United States Cyber Command, Our History.”

3. David Vergun, “CyberCom’s Partnership with NSA Helped Secure U.S. Elections, General Says,” Defense News, 25 March 2021.

4. U.S. Cyber Command, “United States Cyber Command, Our Mission and Vision,” www.cybercom.mil/About/Mission-and-Vision/; Bruce Sussman, “7 Revealing Quotes from the New Head of U.S. Cyber Command,” Secure World, 4 May 2018.

5. Gina Harkins, “Air Force Warrant Officers Might Solve Cyber Retention: Enlisted CyberCom Leader,” Military.com, 18 September 2018; C-Span, “Video: U.S. Military Operations in Cyberspace,” 15 May 2018.

6. C-Span, “U.S. Military Operations in Cyberspace.”

7. Jason Colquitt, Jeffrey LePine, and Michael Wesson, Organizational Behavior: Improving Performance and Commitment in the Workplace (New York: McGraw Hill, 2021).

8. Department of Defense, “DoDI 1304.31 Enlisted Bonus Program,” 5 November 2020; Department of the Navy, “N13 SRB FY21 Award Plan,” 9 August 2021.

9. Department of the Army, “Memorandum for All Record, Subject: 780th Military Intelligence Brigade Cyber Assignment Incentive Pay (CAIP) and Special Duty Assignment Pay (SDAP) Standard Operating Procedure,” 17 May 2021; Department of the Air Force, “Air Force SDAP Table–V3,” 24 August 2021; Department of the Navy, “N13 SRB FY21 Award Plan”; Department of the Navy, “OPNAVINST 1160, C Special Duty Assignment Pay.”

10. Tim Kane, Total Volunteer Force (Washington, DC: Hoover Institution Press, 2017), 47.

11. Department of the Navy, “OPNAVINST 1160.C Special Duty Assignment Pay”; Sydney Freedberg, “Cyber Force Fights Training Shortfalls: NSA, IONs & RIOT,” Breaking Defense, 27 September 2018.

12. Department of the Army, “Memorandum for All Record, Subject: 780th Military Intelligence Brigade Cyber Assignment Incentive Pay (CAIP) and Special Duty Assignment Pay (SDAP) Standard Operating Procedure;” Department of the Air Force “Air Force SDAP Table–V3.”

13. Carla McCarthy, “Cmdr. Christopher Eng, Commanding Officer, Information Warfare Training Command Corry Station, Talks About the Joint Cyber Analysis Course,” CHIPS: The Department of the Navy’s Information Technology Magazine (October—December 2016).

14. Freedberg, “Cyber Force Fights Training Shortfalls.”

15. McCarthy, “Cmdr. Christopher Eng, Commanding Officer, Information Warfare Training Command Corry Station, Talks About the Joint Cyber Analysis Course”; Department of the Navy, “Navy Interactive On-Net (ION) Computer Exploitation (CNE) Operator Certificate Program, MILPERS 1306-980,” 24 April 2021.

16. Freedberg, “Cyber Force Fights Training Shortfalls.”

17. Courtney Mabeus, “Here’s What’s Next for the Navy’s New W-1s!” Navy Times, 1 November 2019.

18. Vergun, “CyberCom’s Partnership with NSA Helped Secure U.S. Elections, General Says.”

19. U.S. Cyber Command “Working at USCyberCom,” www.cybercom.mil/Employment-Opportunities/.

20. U.S. Cyber Command, “Working at USCyberCom”; U.S. Army Cyber School, “Cyber Warfare Officer (17A).”

21. Chaitra M. Hardison, Leslie Adrienne Payne, John A. Hamm, Angela Clague, Jacqueline Torres, David Schulker, and John Crown, Attracting, Recruiting, and Retaining Successful Cyberspace Operations Officers (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2019).

22. Sussman, “7 Revealing Quotes from the New Head of U.S. Cyber Command.”