On 27 October 1943, Lieutenant Commander Ernest Evans assumed command of the USS Johnston (DD-557).1 Declaring to his new crew and guests, “This is going to be a fighting ship,” he motioned toward the bunting-draped destroyer and added, “I intend to go in harm’s way, and anyone who doesn’t want to go along had better get off right now.” He continued resolutely, “I will never again retreat from an enemy force.”

In recognition of his valiant spirit and heroism in fighting his ship until she sank in the Battle off Samar on 25 October 1944, Evans posthumously was awarded the Medal of Honor, and the culture he set serves as an example to all Navy ships striving for battle-minded and combat-ready crews.2

To live up to that example, the Naval Surface and Mine Warfighting Development Center (SMWDC) should expand schoolhouse capacity beyond officer-centric warfare tactics instructor (WTI) courses to include enlisted tacticians, and the Navy should open WTI billets to

enlisted sailors to supplement officer tacticians on board ships. This would improve the Navy’s investment in the surface force’s combat effectiveness and lethality across all surface navy combatants and foster a culture of learning and excellence throughout all ranks and ratings.

The Enlisted Advantage

Elevating enlisted surface warfare specialists to WTIs would support the Navy’s goal to increase training and education across the force. The establishment of the new Director of Warfighting Development (OPNAV N7), the Chief of Naval Operations’ Fragmentary Order 01/2019, and the Education for Seapower Strategy all point to an increased emphasis on tactical, operational, and strategic proficiency.3 These organizations, documents, and directives echo the idea that every sailor must have better professional naval education—whether academic, technical, or tactical—to increase the Navy’s capabilities and enable the service to prevail in any fight.

Some may argue that enlisted professionals are solely technicians, and officers are the tacticians. In the age of sail or steam, this was true. But to say enlisted personnel are not tacticians in the modern digital navy ignores the manning of every current combatant’s watch floor. Specifically, in the Ticonderoga-class cruisers and Arleigh Burke–class destroyers, the combat information centers (CICs) have evolved from the age of optical gunnery to become the center of the combat team. CICs are led by the captain and, in his or her absence, the tactical action officer—a role generally reserved for SWO department heads. Department heads receive six months of training on warfare tactics and capabilities at the Surface Warfare Officers School and a follow-on two to four months of combat systems training at the Aegis Training and Readiness Center in Dahlgren, Virginia.

But behind the tactical action officer, various warfare area coordinators run their own subordinate watch teams of supervisors and systems controllers, to execute orders from, and provide recommendations and status updates to, the tactical action officer. The antiair warfare coordinator, surface warfare coordinator, and combat systems coordinator are persistently on watch while under way, and in certain situations or on certain ships, the antisubmarine warfare evaluator and ballistic-missile defense officer can fill supplemental warfare coordinator roles.

On cruisers, which often serve as the air-defense commander within a carrier strike group, a force air warfare coordinator and force tactical action officer may be stood up. Of these watch stations, only the antisubmarine warfare evaluator shall be, by Commander, Naval Surface Forces, instruction, a qualified SWO; every other role, including the tactical action officer, may be filled by a commanding officer–designated sailor, including warrant or limited duty officers, division officers, or enlisted personnel.

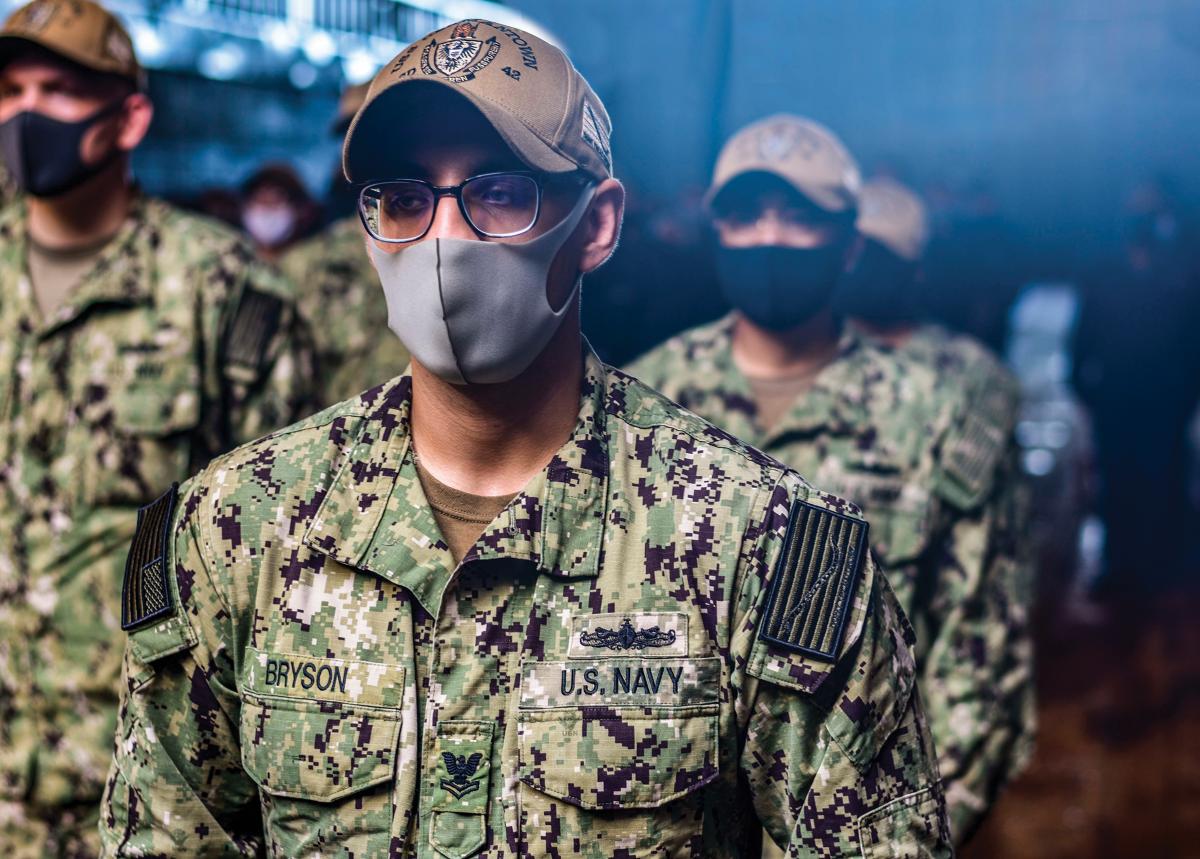

As the Navy drives the surface community to circadian rhythm watch bills, senior watch officers are encouraged to build three or four watch sections, which means there are anywhere from 9 to 12 qualified warfare coordinators required at a minimum to fulfill those roles.4 Inherently, there are not enough qualified senior first tour, second tour, or warrants and limited duty officers to fill these roles. Frequently, enlisted sailors as junior as E-5 fill more than half of these roles, learning through on-the-job training and under-instruction watch standing prior to qualification. These same enlisted personnel serve as tacticians on watch, and then off watch continue to serve as leading petty officers and divisional and departmental chief petty officers. They are expected to lead sailors on the deckplates, fix equipment, and manage division or department administration, in the same way enlisted WTIs in the rotary-wing community are leaders in their work centers and squadrons.

The value of surface enlisted WTIs could be multiplicative. Surface enlisted personnel would be empowered to describe the “why” behind the criticality of material readiness when they can give their sailors expert-level explanations of the role their gear plays in the tactical employment of the ship. Enlisted WTIs would be an example to strive for—one that embodies a warfighting and mission-first focus on training and execution, which could be rewarded in the evaluation and promotion process. Enlisted WTIs could mentor and train and culturally build bridges with the junior sailors standing multiple shipboard watch stations. For instance, a senior SPY-1 radar technician who is a qualified WTI could instruct junior sailors on the most up-to-date sensor employment procedures with the credibility and relatability of having come up through the enlisted ranks.

Finally, enlisted WTIs could supplement the schoolhouse production and shipboard presence of SWO WTIs. A second-tour division officer or department head who completes the WTI course will serve on board any given ship for a maximum of 18 months, prior to a multiyear production tour ashore. A first-tour department head may fleet-up on the same ship for a total of 36 months on board. Consider a SWO WTI’s tour in conjunction with an E-6 WTI on his or her second reenlistment, already qualified at multiple watch stations and now heading back to sea for another five years. That sailor may see two or three deployments and training cycles compared with one or two for the SWO. The unique training, proficiencies, authorities, and responsibilities of officer WTIs can be reinforced by those of enlisted counterparts, in terms of continuity and depth of expertise throughout the ranks. Enlisted WTIs likely would be high performers and could take their expertise into the chiefs’ mess during their five-year enlistment.

In a follow-on enlistment, enlisted WTIs could be detailed to a fleet training command such as SMWDC, the Afloat Training Group, the Center for Surface Combat Systems, Aegis Training and Readiness Center, and Tactical Training Group Atlantic/Pacific, or to the deployment-certifying Carrier Strike Groups 4 or 15. Having raised the tactical bar ashore, he or she could return to a ship as an E-8 or E-9—a leader with more than a decade of deckplate tactical experience informed by the highest level of warfighting proficiency and standardization overseen by SMWDC. The result would be not only battle-minded ship crews, but also a battle-minded surface navy team, reinforced by unique warfighting expertise and proficiencies across the officer/enlisted enterprise.

An enlisted WTI program, however, would not supplant SWOs as tacticians. Rather, it would recognize and relieve some of the SWO career pressures to demonstrate competencies in joint billets, finance roles, personnel management, operational and strategic staffs, and graduate education. These pressures pull SWOs away from gray hulls as they progress toward higher levels of responsibility. Increasing the WTI cadre by including enlisted personnel would complement and serve the broader mission of tactical excellence.

A Program Proposal

Any new personnel and training program will involve administrative and financial burdens. However, the following is an initial framework for training and certifying enlisted WTIs. It includes a road map for how to fit the three to four months of intense academic work in the WTI course of instruction into sailors’ careers and ship or shore schedules. There currently are four WTI courses: integrated air and missile defense; antisubmarine/antisurface warfare, amphibious warfare, and mine warfare. Access to these courses should initially be open to specific ratings and/or Navy enlisted classifications (NECs)and support career growth by aligning qualifications with warfare areas:

Integrated Air and Missile Defense

- Aegis fire controlman

- Operations specialist, with air intercept controller or tactical information coordinator NEC

- Gunner’s mate, with the NEC of vertical launch system (VLS) technician

- Electronics technician or interior communications electrician

Antisubmarine/Antisurface Warfare

- Operations specialist, with antisubmarine/antisurface warfare tactical air controller or Harpoon engagement planning operator NEC

- Gunner’s mate, with non-VLS NEC

- Sonar technician, surface

- Fire controlman, with Tomahawk strike manager or Harpoon engagement planning operator NEC

Amphibious Warfare

- Boatswain’s mate, with senior experience in ship-to-shore amphibious movement

- Operations specialist, with experience on a naval surface fire support (NSFS) team

Mine Warfare

- Mineman

Each of these sailors would be at least an E-5, have a warfare coordinator qualification (exceptions in the amphibious and mine warfare courses of instruction considered), be recommended by his or her commanding officer, and have a minimum of three years remaining on his or her enlisted contract after completing the WTI course or commit to signing an extension to meet or exceed that goal. In this way, SWO tacticians and commanders would select the best and brightest enlisted sailors to join the WTI ranks. And a minimum production tour of three years after the course of instruction would ensure the minimum return on investment for an enlisted WTI is equal to at least the maximum consecutive number of months any SWO WTI could be on board a ship as a fleet-up department head.

Sailors would complete the WTI course en route to sea or shore duty. Those already assigned to a ship could attend with permission of their commanding officer during a ship’s maintenance phase. Ships regularly send sailors to multimonth schools during maintenance phases to allow sailors to acquire additional NECs. While they are in training, the equipment managed by the combat systems or operations technicians often is deactivated from regular maintenance because of inactivity. This allows more senior sailors to get high-end tactical training with limited impact to those remaining on board.

One concern that may arise in response to this program is potential conflicts between a standard SWO department head and tactical action officer arguing with an enlisted WTI warfare coordinator about the right combat decision. This, however, is a culture problem, stemming from the Navy’s outdated conceptions of enlisted and officer roles. As retired Fleet Master Chief Paul Kingsbury argued in his May 2019 Proceedings article, today’s enlisted personnel have “higher retention standards, [operate] technically advanced warfighting systems, and [receive] training and education yielding a more professional and capable enlisted force.”5 It is time for the Navy to rethink enlisted sailors’ capabilities—and for all officers to treat them accordingly. Should conflicts between enlisted WTIs and officers arise in CICs, SWOs should deal with them in the same way they would in a disagreement between two commissioned officers: with tact, patience, justice, firmness, kindness, and charity.

‘Own Tomorrow’s Fight Today’

The surface navy is at an inflection point. Flat budgets may stagnate shipbuilding or the acquisition of advanced capabilities.6 U.S. alliances and forward presence are being challenged by peer powers with aims for regional hegemony. To address these challenges, the Navy is striving for more complex predeployment training higher-end watch team training and establishing specific tactical competencies for SWOs, from division officer all the way to major commander.7 If the Navy wants to “own tomorrow’s fight today” with combat-ready crews, it must follow Commander Ernest Evans’ advice to make “fighting ships” with fighting crews of officer and enlisted tactical specialists.8 Now is the time to broaden the WTI program to include surface enlisted professionals.

1. LCDRs Thomas J. Cutler and Rick Burgess, USN (Ret.), “Lest We Forget: Ernest E. Evans, VX-8,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 132, no. 3 (March 2006): 94, usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2006/march/lest-we-forget-ernest-e-evans-vx-8.

2. PO3 Janine F. Jones, USN, “Bunker Hill Leads the Way, Earns Battle ‘E’,” U.S. Navy, 6 August 2016, public.navy.mil/surfor/cg52/Pages/Bunker-Hill-Leads-the-Way-Earns-Battle-E.aspx.

3. Ben Werner, “Navy Quietly Stands Up Warfighting Development Directorate (OPNAV N7),” USNI News, 12 November 2019, usni.org/2019/11/12/navy-quietly-stands-up-warfighting-development-directorate-opnav-n7; ADM Michael Gilday, USN, “Fragmentary Order 01/2019: A Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority,” U.S. Navy, 4 December 2019, public.navy.mil/bupers-npc/reference/messages/Documents/NAVADMINS/NAV2019/NAV19277.txt; and Thomas B. Modly, Education for Seapower Strategy 2020, 4 March 2020, media.defense.gov/2020/May/18/2002302033/-1/-1/1/NAVAL_EDUCATION_STRATEGY.PDF.

4. Megan Eckstein, “Fleet Finding New Sleep-Sensitive Watch Schedules Boosts Crew Performance, Efficiency,” USNI News, 15 July 2019, news.usni.org/2019/07/15/fleet-finding-new-sleep-sensitive-watch-schedules-boosts-crew-performance-efficiency.

5. FMC Paul Kingsbury, USN (Ret.), “Make Better Use of the ‘Super Chiefs,’” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 145, no. 5 (May 2019).

6. Ben Werner, “SECDEF Esper Preparing for Future Defense Spending Cuts,” USNI News, 4 May 2020, news.usni.org/2020/05/04/secdef-esper-preparing-for-future-defense-spending-cuts.

7. Megan Eckstein, “Navy Rethinking Fundamental Training for SWO Skills, Crafting More Complex Pre-Deployment Exercises,” USNI News, 27 January 2020, news.usni.org/2020/01/27/navy-rethinking-fundamental-training-for-swo-skills-crafting-more-complex-pre-deployment-exercises; Megan Eckstein, “Naval Surface Forces Looking Closely at Warfare Training for Individuals, Watch Teams, USNI News, 13 January 2020, news.usni.org/2020/01/13/naval-surface-forces-looking-closely-at-warfare-training-for-individuals-watch-teams; and VADM Richard A. Brown, USN “Owning Tomorrow’s Fight Today: A Surface Warfare Update,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 145, no. 12 (December 2019), usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2019/december/owning-tomorrows-fight-today-surface-warfare-update.

8. Brown, “Owning Tomorrow’s Fight Today: A Surface Warfare Update.”