I first met Keith through a LinkedIn post that caught my attention because another retired service member unprofessionally attacked him. Before I blocked the offender, I told him I found his demeanor inappropriate for the forum. That earned me a “like” from Keith, and we connected. This was just a few weeks before George Floyd’s murder sparked protests—and conversations—about race in America. The talk of “White privilege” and “Black lives matter” was not in my middle-aged White man comfort zone but talking to Keith made me think back on my own experience and life and Navy, and how different it must be from his own. Below are parts of that conversation.

Cordle: I grew up in north Georgia, a blue collar, southern enclave in the Blue Ridge mountains near where my parents were raised. My mother was a career teacher and my father a Navy “Mustang” who retired as a lieutenant commander. Our large family consisted of teachers, farmers, truck drivers, and military veterans. In my fairly diverse town, there was definite bifurcation; East Side High School was predominantly Black, and West Side was Whiter. I attended a private high school, driving through the East side with a Confederate Flag license plate. I don’t think I had a substantial conversation with a Black person until I joined the Navy at 18. Not because I consciously avoided it—it just never happened.

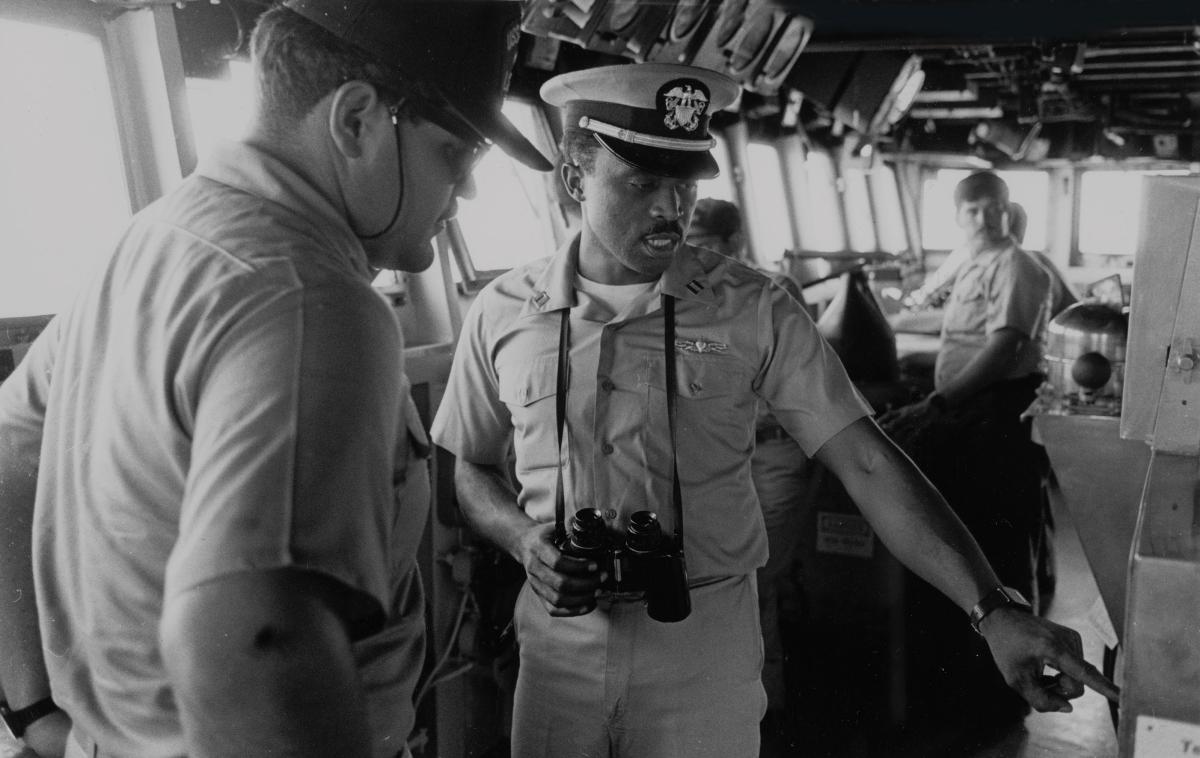

Green: I was born a poor Black child, and I stayed that way until I joined the Navy. I had rusty knees, ate government cheese, and looked for “strange fruit” in the Poplar trees. My enlisted sailor father had no Navy memorabilia in our house, having left the service after almost 18 years without a pension or veterans’ benefits—bitter, damaged, and having served on at least eight ships and four trips to Vietnam. When I joined the Navy in 1975, I experienced quite a culture shock when the service did not quite live up to its stated ideals in the recruiting brochures. I wanted to “be Black and Navy too,” as the recruiting posters said, but being Black kept getting in the way. The backlash to the initiatives of Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Elmo Zumwalt was in full swing and I was cheated and punished for outperforming all but one student in my A-school class. I read Zumwalt’s memoir On Watch as a 19-year-old seaman, and it was eye-opening. The chapter “Sailing Second Class” went a long way toward explaining my father’s bitterness.

Cordle: My family was centered around the Navy. Dad was enlisted for about 12 years, then picked up for OCS, served on a variety of ships, and for two years in Vietnam. Our house was filled with Navy memorabilia, and our conversation centered on ships, sailors, and the sea. I really didn’t give serious consideration to many paths other than the Navy. I left home for the U.S. Naval Academy. I would love to detail my 30-year voyage of discovery of “race and equality,” but there is not much to tell. I did my job and I think I treated sailors and officers equally based on their talent and performance and not their color or gender, but I guess you would need to ask my shipmates about that.

Let’s look at some recent developments. The first Black service chief (Air Force) was just sworn in—70 years after service integration—and the first Black Secretary of Defense was appointed in 2021. Military data recently revealed low percentage of Black people serving as officers and in other leadership positions, and how that imbalance translates in higher injury and disability rates among Black soldiers and sailors.1 In May 2020, Proceedings published a list of the 240 Navy flag officers. There was a total of 8 Black officers out of 240. That is 3.3 percent for a demographic that makes up 13 percent of the U.S. population and 7.5 percent of all Navy officers. There were 23 female faces. That is about 10 percent while women represent just over 50 percent of the population and 18 percent of the Navy officer corps.

Green: In the Navy, performance is king. Problems often arise, however, when you encounter a racist outlier, or when you are being judged by people who don’t know you, such as during promotion board deliberations. I hated taking those promotion board photos. You must prove yourself to every new person if you are minority or a woman. Implicit bias is real, and Navy and Navy-sanctioned studies have proven this for decades. This helps explain the dearth of Black faces in the flag community. Decisions made years earlier impact the results you see today. In the book Inspiring Innovation: Examining Contributions Made by Vice Admiral Samuel L. Gravely Jr. (Van Beuren Studies in Leadership and Ethics), some of the first 50 Black flag officers in the Navy briefly discuss their careers and some stories of discrimination and racism that ring true to me. That the Navy has not achieved parity in the higher ranks is the result of many things, but institutional and cultural resistance are part of the problem. Another reason is the lack of sharing of stories and experiences. Some Black junior officers are sharing their experiences now and that is a good thing.

Cordle: Interesting. Here’s a data point: Over the past ten years, there have been six flag officers in a certain position that is normally a precursor to other higher positions. Three of these flags were White, and three were officers of color. All three White officers went on to a higher echelon and more stars; none of the non-White ones did.

Green: If you take the flag statistics at face value, you could assume that White female officers perform better than Black officers of either gender, but not as well as White men. If that is not the case, then what do these statistics indicate? In the current racial climate, Navy leaders are indicating a willingness to listen. I wish they had called for written stories, as did the Air Force, which received 27,000 single-spaced pages of stories of discrimination and racism in its service. It is time to look at the trends in promotion, selection, retention, command climate surveys, and determine how much discrimination and sexual harassment and assault are contributing factors. CNO Admiral Michael Gilday’s decision to eliminate divisive symbology on naval bases means that the service once again is entering a period of institutional self-assessment and change, but without buy-in from senior leaders and the rank and file, little will change. Imagine if leader buy-in had occurred in the aftermath of CNO Zumwalt’s Z-Gram #66 regarding equal opportunity. We might not be having this discussion today.

Cordle: To your point on photos, I saw that there is movement toward eliminating them for review boards in all the services. It never occurred to me that skin color in a photograph could be a deal-breaker for promotion. Who knows what individual prejudices might exist in the board room? How can the military turn the corner to increase the number of minority officers over time? Use a quota system, a minimum percentage? Set aside a certain number of promotions for minorities and women? Most of these actions come with unintended consequences and would be nonstarters. I don’t know the answer.

Task Force One Navy is a great step toward addressing these issues; given our exchange, the following are our recommendations to achieve Task Force One Navy objectives:

• Commit to systemic, measurable change and acknowledge that racism is an issue in the Navy.

• Require progress and goals accomplished as opposed to rewarding “effort.”

• Speak in plain terms about the obstacles, challenges, and barriers women and service members of color experience, and create an offense of discrimination and racism and add it to the Uniform Code of Military Justice.

• Document where the Navy is in the process of becoming more diverse so there is a baseline on which to improve.

• Insist on buy-in from leaders at all levels, and continue to eliminate racist symbology, starting with renaming the USS John C. Stennis (CVN-74).2

• Create a military discrimination complaint process that includes professional investigation, empowers equal opportunity personnel, and tracks repeat offenders and retaliation. Disclose the past ten years of discrimination complaints and the number/percentage substantiated.

• Institute a comprehensive, professional, and objective program for evaluating how implicit and explicit bias affect service members and their families. Mental health resources should be considered and expanded.

• Incorporate lessons from past mistakes into current and future initiatives.

• Investigate all cases of discrimination using an independent entity and have a second team look at all cases that are not substantiated.

• Prosecute those found to have committed offenses of racism and discrimination. Publicize to help get the word out and show that the system works.

These changes are essential for the Navy to succeed in this long-overdue commitment to lasting change.

1. Zachary Cohen and Janie Boschma, “Military Data Reveals Dangerous Reality for Black Service Members and Veterans,” CNN, 13 June 2020.

2. LCDR Reuben Keith Green, USN (Ret.), “The Case for Renaming the USS John C. Stennis,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 146, no. 6 (June 2020).