While the debate about renaming military bases named for Confederates rages throughout the land, the West Wing, the Pentagon, and in the halls of Congress, I want to bring the discussion closer to the waterfront. Since the military and defense leaders seem to be amenable to hearing what the “dark-blue” and “dark-green” soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Marines have to say, and since most of them are not in a position to speak frankly, I thought I would make an attempt. This will be an uncomfortable conversation—one I only committed to writing on after a good deal of research—and I ask readers to conduct their own research before weighing in or dismissing the idea out of hand.

If South Carolina Senator Strom Thurman and Alabama Governor George Wallace were the face and voice of the Southern Dixiecrats, then Mississippi Senator John C. Stennis was the heart, soul, and brains of the white supremacist caucus in the 1948 Congress. The Dixiecrats were the faction of the 1940s Democratic Party that consisted of malcontented southern delegates who protested the civil rights plank in the party platform, and President Harry S. Truman’s advocacy of that plank. The blinding of Army Sergeant Isaac Woodard Jr. by a South Carolina policeman in 1946 strengthened Truman’s resolve.

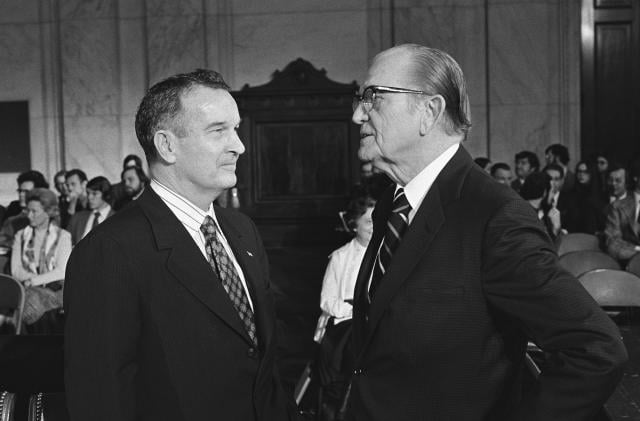

Stennis, on the other hand, almost singlehandedly derailed the cultural changes being attempted by then-Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Elmo Zumwalt, as Zumwalt detailed in his memoir, On Watch. Stennis was vehemently opposed to black equality, and spent his entire career, both as a Mississippi prosecutor, judge, and state senator attempting to ensure it did not happen. He ordered congressional subcommittee hearings on “Permissiveness” in the Navy, led by Louisiana Senator Eddie Hebert, in a thinly veiled attempt to thwart Zumwalt’s initiatives. Thurman, Wallace, and Stennis all signed the infamous Southern Manifesto—a document written in 1956 in opposition to racial integration in public places—as did all Southern Democrats from the former Confederate states.

During a meeting on the topic, requested by Zumwalt, Stennis told Zumwalt, “Blacks had come down from the trees a lot later than we did.” The subcommittee ignored the mountain of evidence Zumwalt presented that showed systematic and pervasive racism in the Navy. Zumwalt still prevailed, however, with his seminal directive, Z-Gram Number 66, on equal opportunity, but the battle continues.

Stennis’s record championing white supremacy is long. Matthew Yglesias wrote a 26 November 2007 Atlantic article, “The White Supremacist Caucus,” which identified Stennis as being ahead of his time as an advocate of torture:

As a prosecutor, he sought the conviction and execution of three black men whose murder confessions had been extracted by torture. The convictions were overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court in the landmark case of Brown v. Mississippi (1936) that banned the use of evidence obtained by torture. The transcript of the trial indicates Stennis was fully aware of the methods of interrogation, including flogging, used to gain confessions.

While I knew this about Stennis when I wrote my memoir (I included it), Black Officer, White Navy, I did not know enough. Jesse Curtis’s April 2014 thesis, Awakening the Nation: Mississippi Senator John C. Stennis, the White Countermovement, and the Rise of Colorblind Conservatism, 1947–1964, was an eye-opening read for me. One need only read the first 20 pages to understand why the Stennis name on a diverse U.S. warship is not only problematic, but disgraceful. That he was nominated by President Ronald Reagan, whose own racist beliefs were revealed in a recent tape recording from the Nixon Presidential Library, is instructive. Historian Timothy Naftali uncovered the tape, in which Reagan used racist language to denounce African diplomats: “To see those, those monkeys from those African countries—damn them, they’re still uncomfortable wearing shoes!” The disclosure led to Reagan’s daughter publicly asking for forgiveness for her deceased father, acknowledging that the comments were racist. I have no problem with Ronald Reagan’s name on a warship—there is no evidence that he ever explicitly acted on these views—but Stennis is in a different category altogether. Curtis’s thesis makes clear this should not stand.

I believe the military is right to seriously consider removing the names of Confederate soldiers from military bases and facilities. The United States is the only nation to my knowledge that erected monuments and bestowed honors on the very people responsible for the death of many thousands of loyal soldiers and sailors in a fight to retain their states’ right to enslave millions of people of African descent. I can recall vividly and with much emotion the day I boarded the USS Gettysburg (CG-64) as the in-port training department head for Destroyer Squadron Eight in Mayport, Florida, saluted the ensign on the fantail, and turned to see the officer of the deck standing beside a display of the U.S. flag and the Confederate battle flag, awaiting my salute. For the first and only time in my career, I failed to render the proper salute, instead simply walking past without a word or gesture of any kind. I could not do it.

I often have thought about what it must be like for a minority sailor to receive orders to and serve in the USS John C. Stennis (CVN-74). Most sailors—and Navy leaders—have little idea of his background, but the Navy, as an institution, has a moral obligation to know. And, it should act. I recommend the Navy formally reconsider whether it is appropriate for a capital ship to bear the name of an avowed, lifelong white supremacist with a record of condoning torture of U.S. citizens.

I received a call recently from the widow of a respected and accomplished Navy surface warfare captain, who tearfully recounted to me the story of how her black husband called her, and through tears of anguish and despair, told her that his reporting senior had told him that he would not be recommending him for early promotion to rear admiral because he had to take care of “his people,” meaning “white people.” This distraught captain was black. Stennis would have approved. His widow said it was only the second time she had ever seen her proud warrior husband shed tears. She also recounted that many black spouses of fellow naval officers had shed similar tears in her presence on behalf of their husbands as they recounted similar stories of discrimination and betrayal. I lived it and wrote about it. Admiral Zumwalt saw this firsthand, and it changed him; some who worked for him say it traumatized him. He acted to make changes, in the face of massive resistance, both inside and outside the lifelines, and I challenge today’s leaders to match his courage.

If the Navy is serious about listening to minority sailors and officers, I hope it will consider the optics of the future USS Doris Miller (do you recognize the name—look it up!) and the current John C. Stennis steaming together or tied up in the same basin. One sends a strong message of inclusivity, and the other an immoral and cringeworthy one. I started my career in Charleston, South Carolina—Senator Thurmond’s home state—under the command of an officer whose dashboard was plastered with stickers honoring the Confederate cause. He damaged my career early, but I recovered. I ended my career decades later in Florida under a commanding officer and subsequent immediate superior in command who was born and raised in Alabama—Governor Wallace’s home state. He took care of “his” people too, including a blatant and unstable racist who succeeded him and who professionally and psychologically abused me until I filed a well-documented five-page discrimination complaint against him (that illegally went unprocessed) to get his attention. They damaged my career, helped end it, and I am still in recovery, decades later. As I read the derisive and racist LinkedIn comments (and responded to some of them) about the CNO’s decision to ban the Confederate flag, it became clear that this will not be a seamless transition from venerating the divisive symbols of the past to a more inclusive Navy.

I have thought long and hard about what I would have done had I received orders to the John C. Stennis when I was on active duty. I can imagine some shipmates smirking at me during Black History Month and saying, “You know Stennis was a diehard racist, right?” I know minority sailors who served in her, and I cannot imagine doing so myself. My family has had skin in the game for generations: My grandfather served in World War II and died in a VA hospital in 1946. My father served in both Korea in the Army and on board eight ships in the Navy, including four tours to Vietnam. Today’s sailors, Marines, and officers should not have to make the psychologically damaging choice of speaking up or serving in silence in a vessel named for an ardent segregationist and white supremacist, who condoned beating the skin off black people until they either confessed or died. It is incompatible with American values and the recent directives from the Navy to expect for them to have to do so.

When the Army banned the Confederate flag from bases in Vietnam, because the Army was “tearing itself apart,” I am sure that John C. Stennis was one of the powerful Southern voices in Congress and elsewhere that forced the Army to reverse that decision. I hope that there are powerful voices in the Department of Defense, the Navy, and Congress today that can rectify this decision, because it is the right thing to do. Show the sailors and officers that this current willingness to listen will be followed up with concrete, lasting actions that make for a more cohesive, diverse, and stronger fighting force. I can think of no better candidate than William S. Norman for whom to rename the John C. Stennis, Admiral Zumwalt’s minority affairs assistant, who, according to Zumwalt, did more than anyone to improve the plight of minorities in the Navy.