Twentieth-century British naval theoretician Sir Julian Corbett stated that the object of naval warfare is to control the sea lines of communication (SLOCs).1 All Indo-Pacific states, including the United States, have long enjoyed unfettered access to the surrounding SLOCs under the regional maritime regime. By using gray-zone tactics such as maritime militias, a militarized coast guard, and prosecution of legitimate competing commercial vessels and platforms, China has slowly attempted to challenge the existing free-and-open maritime commons in the first island chain, referring to Taiwan as “essential strategic space for China’s rejuvenation” and a “springboard to the Pacific” in official military writings.2 Similarly, Admiral Ernest King dubbed Taiwan “the cork in the bottle” of Japanese SLOCs during World War II.3 Were Taiwanese sovereignty ever so challenged as to call into question the security of the SLOCs it straddles, a revisionist and belligerent China could threaten these vital economic links. Speaking strictly from this perspective, and without regard for the persuasive political and moral considerations of continued Taiwanese sovereignty, it is decidedly in U.S. national interest to deter a hostile takeover of Taiwan by China and maintain the kinetic capabilities necessary to protect Taiwan if deterrence fails.

A Modern Reading of Corbett

A prolonged high-end conflict with the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) will prove incredibly difficult for the U.S. Navy. It is no secret that China would seek to sever the Navy’s vulnerable supply networks, targeting resupply vessels and depots across the Indo-Pacific.4 While it is possible the United States will strengthen or otherwise diversify its logistics network, the confines of geography will endure—in a Taiwanese contingency, China would be fighting (and resupplying) in its strategic backyard.5 If deterrence fails, the Navy must be prepared to fight and win in as short a timeframe as possible.

Does this mean a Mahanian-style concentration-of-forces, winner-take-all battle? Not necessarily. As Corbett puts it, a battleforce need not be “huddled together like a drove of sheep, but distributed with regard to a single common purpose, and linked together by the effectual energy of a single will.”6 In this regard, the distributed maritime operations (DMO) concept is clearly Corbettian in nature. As described by Vice Admiral Philip Sawyer, DMO is “geographically distributed naval forces integrated to synchronize operations across all domains.”7

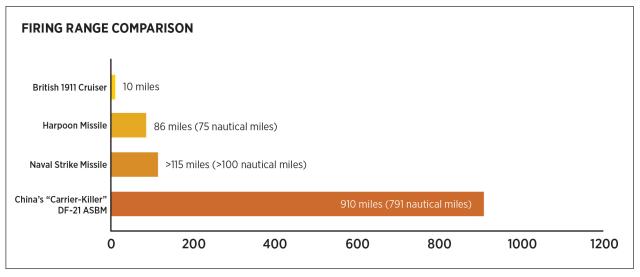

The theories Corbett espoused in Some Principles of Maritime Strategy, however prophetic, simply cannot be applied 111 years later without significant modification. When Corbett wrote his seminal work in 1911, the unmatched guns of the British battle fleet had a maximum firing range of around ten miles.8 Today’s antiship missiles enjoy effective ranges of hundreds if not thousands of miles. A simple and enduring truth of kinetic warfare is the connection between shooter and target—who can shoot farthest and most effectively? For Corbett, this meant cruisers: fast, lightweight ships serving as “eyes of the fleet”—dedicated to seeking out enemy combatants and reporting their position and maneuvers to more capable battleships for subsequent engagement.9 Of course, the intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities of Corbett’s cruisers are a far cry from those of the U.S. Navy’s Ticonderoga class, cruisers arguably just as ISR-capable as their Arleigh Burke–class destroyer compatriots, or the aircraft employed by a carrier strike group.10 Shipborne sensors offer individual units and networked strike groups a wide tactical horizon compared with the dreadnoughts of old. These advances in ISR have been matched equally by the increasing range of shore-based and sea-based strike capabilities.

For instance, China’s “carrier-killer” DF-21D antiship ballistic missile (ASBM) has a range of 910 miles and could be positioned anywhere along China’s coast or within its growing South China Sea island claims.11 For that reason, organic shipboard sensors may not provide a safe enough range from which to engage a PLAN ship within the first island chain without accepting undue risk from shore-based ASBMs. Even discounting the formidable shore-based assets of the PLAN and People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF), U.S. and partner assets would still be forced to position themselves at a significant range in order to more safely engage PLAN vessels at sea. China is winning the “range war.”12 The eyes of the fleet must look farther over the horizon, be placed closer to the potential theater, or both.

The Range War

The shooter who can strike first and effectively at range will have a massive advantage. However, it is unlikely that the United States or partner nations would strike first—any strike would likely be in response to Chinese aggression.13 Therefore, the United States would then have to respond effectively and near-instantaneously to a widespread and coordinated Chinese salvo against Taiwanese, Japanese, and U.S. targets across the first island chain. Such a task would require sufficient targeting data with which to guide a reciprocal strike.

Corbett’s eyes of the fleet now include satellites and other inorganic sensors that provide strike assets with battlespace awareness well beyond their individual tactical horizons and can offer ISR capabilities at essentially global ranges. Sensors employed by ships and other strike resources may not be able to offer sufficient organic targeting data on potential targets without accepting undue risk to their host platforms. Therefore, inorganic targeting systems must not only be available, but also sufficiently distributed and diversified to support maximum lethality at a moment’s notice. This represents a necessary expansion of the shooter-to-target kill chain model.

A Taiwan Contingency

Current Navy plans for a “Taiwan contingency” involve deploying Marines to the Ryukyu Islands, armed with ASBMs.14 Current Japanese strategy supports the maintenance of a defensive “southwestern wall” along the Nansei Islands, including radar and intelligence-gathering stations alongside ASBMs.15 While steps in the right direction, neither currently provides for the effective use of “shooters” outside the first island chain, theoretically with more striking power and less vulnerable to a neutralizing Chinese first strike.

The Ryukyu Islands, sovereign Japanese territory, must be furnished with a combination of over-the-horizon radars, electronic warfare systems, and other sensors to provide positional data on PLAN units to U.S. and partner strike assets outside the first island chain. These sensors could include mobile vehicle-based search radars such as the AN/TPS-80 and even fixed installations akin to Aegis Ashore.

It is not sufficient to depend solely on the satellite-oriented or GPS-reliant data sources of recent conflicts.16 Chinese strategic writings make explicit reference to “the enemy’s even greater reliance on space systems” and that “select attacks against the critical node targets of the enemy space systems” would become necessary if facing “space strikes.”17 Without total confidence in uninterrupted ISR from U.S. or partner satellites, U.S. strike forces would be left with few inorganic options with which to guide strikes against Chinese forces. Identifying and developing alternative and diverse means of data transmission—whether by undersea cables or by a collection of wireless repeaters including waterborne and airborne nodes—will also be key.

The Other Side of the Strait

Of course, one argument against “sensorization” in the first island chain is that these sensors would be targeted in the early stage of a high-end conflict. However, the presence of mobile sensors could complicate PLAN targeting efforts ahead of a first strike. Similarly, whether fixed or mobile, the presence of sensors along the first island chain would impose additional opportunity costs on the PLAN by forcing expenditure of its finite munitions. In the event of such a high-end conflict, these sensors could offer up-to-the-minute positional data on PLAN vessels prepositioning themselves in advance of an invasion of Taiwan even after their destruction.

Furthermore, the destruction of these sensors would clearly communicate Chinese intent without unduly risking strike assets or personnel. Given that these sensors would likely be placed on Japanese soil, striking them would compel a Japanese military response, politically and strategically complicating Chinese war plans. Finally, the United States’ current satellite-oriented targeting infrastructure is equally—if not more—vulnerable to attack early in a conflict, underlining the importance of diversifying sensors and placement.

How China might attempt to mold regional perceptions of the installation of these sensors is uncertain. However, any such concern rings hollow in the context of China’s persistent and continued militarization of its legally dubious territorial claims in the South China Sea. Japan has increasingly made public its keen interest in Taiwan’s continued sovereignty. It seems reasonable to expect that Japan and the United States would be willing to engage in a joint sensor emplacement in the first island chain. In addition, the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments has published extensive studies on the concept of “deterrence by detection,” wherein China or other actors would be “less likely to commit opportunistic acts of aggression if they know they are being watched constantly and that their actions can be publicized widely.”18 Such a sensor network could serve a valuable purpose in times of peace as well as war.

The placement of networked sensors along the first island chain would be a logical extension of current and planned U.S. and Japanese operational planning in the region. In fact, the destroyer USS John Finn (DDG-113) recently executed a successful SM-6 strike on a target 250 miles away without the use of organic sensors.19

The United States and Japan clearly understand the geographical advantages offered by the first island chain and have increasingly dedicated manpower and resources to constrain China’s malign activities in the region. However, overreliance on satellite targeting sources and increased vulnerability to strike assets within the first island chain underscore the need for distributed maritime operations. The union of distributed inorganic sensors inside the first island chain and strike forces situated remotely outside will improve U.S. deterrence and responsiveness in defense of Taiwan and the SLOCs it straddles.

1. Julian Stafford Corbett, Some Principles of Maritime Strategy (London: Longsman, Green, and Co., 1911), 94.

2. China Aerospace Studies Institute, The Science of Military Strategy (Beijing: Military Science Press, 2013).

3. Iskander Rehman, “Why Taiwan Matters,” Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 28 February 2014.

4. Christopher Woody, “In a War with China, the U.S. Navy’s Warships Might Not Be the First Target,” Business Insider, 5 June 2020; and Liu Xuanzun, “PLA Conducts 1st Underwater Port Demolition Test Providing Data for Future Combat,” Global Times, 25 October 2021.

5. David Axe, “China’s Huge Naval Forces Are Making U.S. Naval Logistics Vulnerable,” The National Interest, 7 December 2020.

6. Corbett, Some Principles of Maritime Strategy, 131.

7. Edward Lundquist, “DMO Is Navy’s Operational Approach to Winning the High-End Fight at Sea,” Seapower, 2 February 2021.

8. Robert K. Massie, Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea (London: Head of Zeus, 2013), 630–31.

9. Corbett, Some Principles of Maritime Strategy, 112.

10. David Axe, “The U.S. Navy Is Building Cruisers—It’s Just Not Calling Them That,” Forbes, 8 February 2021.

11. Andrew S. Erickson, “The China Anti-Ship Ballistic Missile (ASBM) Bookshelf,” China Analysis from Original Sources, 17 November 2020.

12. David Lague, “Special Report: U.S. Rearms to Nullify China’s Missile Supremacy,” Reuters, 6 May 2020.

13. U.S. Department of Defense, Air-Sea Battle: Service Collaboration to Address Anti-Access and Area Denial Challenges, U.S. Naval War College, May 2013.

14. “Japan, U.S. Draft Operation Plan for Taiwan Contingency: Sources,” Kyodo News, 23 December 2021.

15. Scott W. Harold, Koichiro Bansho, Jeffrey W. Hornung, Koichi Isobe, and Richard L. Simcock II, “U.S.-Japan Alliance Conference: Meeting the Challenge of Amphibious Operations,” RAND Corporation, 2018.

16. Larry Greenemeier, “GPS and the World’s First ‘Space War,’” Scientific American, 8 February 2016.

17. China Aerospace Studies Institute, The Science of Military Strategy.

18. Thomas G. Mahnken, Travis Sharp, Chris Bassler, and Bryan W. Durkee, “Implementing Deterrence by Detection: Innovative Capabilities, Processes, and Organizations for Situational Awareness in the Indo-Pacific Region,” Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 14 July 2014, updated 2021.

19. Sam LaGrone, “Unmanned Systems, Passive Sensors Help USS John Finn Bullseye Target with SM-6,” USNI News, 26 April 2021.