As a topic, illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing needs little introduction. The U.S. Coast Guard Commandant’s 2020 Strategic Outlook stated that IUU fishing “has replaced piracy as the leading global maritime security threat.”1 Indiscriminate IUU fishing techniques, such as drift net release and dynamite detonation, result in annual losses of $37 billion to maritime nations.2 Besides monetary losses, IUU fishing deprives indigenous coastal communities of needed sustenance, which increases poverty and the risk of low-intensity conflict.

Coincidentally, China is one of the world’s worst IUU fishing offenders. Furthermore, China has outfitted its industrial fishing fleet with hardware and collection capabilities that make its boats paramilitary maritime forces. It is a matter of national security to track and interdict these long-ranging fishing vessels, but thus far the U.S. Coast Guard has been unable to field a technology that offers sufficient density of coverage and microfidelity.

A Math Problem Satellites Cannot Solve

Tracking the Chinese fishing fleet largely amounts to a math problem. There currently are an estimated 17,000 high-endurance Chinese fishing vessels capable of operating both as swarms and as dispersed entities.3 Spreading these vessels out over the millions of square miles of other nations’ exclusive economic zones (EEZ) leads to a quintessential needle in the haystack problem.

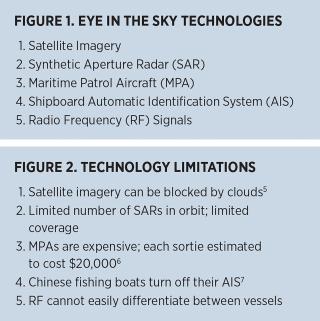

Existing tracking efforts rely heavily on “eye in the sky” technologies that find and ping Chinese fishing boats, where the data is then processed by specialized AI companies. These technologies can be broken into five buckets (see Figure 1) and boast impressive capabilities, but capability gaps remain (see Figure 2).

The Coast Guard has championed orbital technologies, as seen in the Defense Innovation Unit’s recent X3View challenge.4 However, the Coast Guard should also investigate prototyping and deploying low-cost crowdsourced data platforms to provide “ground truths” in addition to these overhead collections.

An Agile Solution

Crowdsourced data platforms should be publicly available, compatible with low-end smartphones, and free to use. Local fishermen can then report Chinese vessels engaging in IUU activities in those fishermen’s sovereign waters. Reports could be broadcasted back to other platform users, the partner nation coast guard (if applicable), and the U.S. Coast Guard. The most analogous way to think of such a platform would be like the driving app Waze, but instead of reporting traffic or speed traps, fishermen would report Chinese vessels engaging in IUU fishing.

This nonstandard intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) could greatly augment the Coast Guard’s detection abilities when employed as a tip-and-cue model. A fisherman’s report would be the “tip,” which allows the Coast Guard to direct private satellite, synthetic-aperture radar (SAR), or radio-frequency operators to “cue” their satellites onto specific patches of ocean. Consistently generating tasking for space assets is far more efficient than sweeping large swaths of the ocean and hoping to get a cold hit. Given the number of fishermen in the Indo-Pacific, this form of ISR would have incredible density of coverage.

Furthermore, if the reports included pictures, then the Coast Guard could obtain valuable amplifying data, such as hull number and cargo on deck. Space assets cannot easily discern hull numbers or draft. In the longer run, data collected by such a platform could be combined with weather and overhead collections to build predictive models of where the Chinese fishing fleet will operate each month.

A crowdsourced platform also could be used in the information operations domain. Pictures and videos of the Chinese fishing fleet employing outlawed fishing practices could be used in press releases to emphasize China’s flagrant violations of good maritime stewardship. Interviews with fishermen in the Philippines reveal that they detest the Chinese fishing fleet presence yet feel like many of their fellow countrymen are unaware of their plight.8 Uniting local seafaring communities via technology would have additional positive effects.

Multiple Proceedings authors have discussed the need to address China’s gray-zone tactics with counterinsurgency (COIN) tactics.9 COIN relies heavily on a positive rapport between blue forces and the local populace. Providing maritime communities with free technology that makes their time at sea safer and more productive would be a good first step in building such a rapport.

The biggest challenge would be getting the fishermen to use the platform and make reports. For starters, the platform would be simple to use and free to download. Once downloaded, a fisherman could view the last known position of hostile Chinese vessels. This is highly valuable since an encounter with Chinese fishing vessels often results in the local fishermen getting their nets cut or vessels rammed.10 And by making reports, a fisherman would indirectly help their comrades avoid unexpected encounters with the Chinese fleet.

The use of crowdsourcing in a contested environment is not unprecedented; during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Ukrainian civilians have increasingly used crowdsourcing applications to report the movements of Russian Army forces.11 The Philippine Navy has had limited success in getting Filipino fishermen to report Chinese maritime militia vessels over via radio, but expressed a need for a more centralized mobile platform.12

Technical Merit and Cost

It is relatively easy to develop a crowdsourced platform. Dozens of such apps exist, although this specific platform would have to be custom built to function offline.13 Basic security and encryption would be essential, and it also would be wise to not require fishermen to include personal identification information (other than an email) when creating an account. Sending the reports’ metadata to an established server provider such as Amazon Web Services would further increase the data’s security and ability to be integrated with Coast Guard dashboards. Back-end quality assurance/quality control programs would serve as filters if China tried to flood the platform with misleading reports.

While space-based assets cost millions of dollars to launch and operate, a crowdsourcing platform could be built for $100,000 and maintained for even less. A team of Stanford University students working on a similar Hacking 4 Defense project were able to field a maritime domain awareness minimum viable product for only $20,000. Making the platform compatible with smartphones would remove the need for custom-built hardware and drive costs down. Furthermore, the potential user base is immense.

Deployment

The U.S. Coast Guard specializes in building partnerships with fishing communities and fisheries enforcement agencies, both domestically and internationally. Once the first version of the platform is built and beta tested, the Coast Guard should showcase it to partner nations. Since the platform would be easy to use, training would take a matter of minutes. Countries most affected by Chinese IUU fishing—such as Ecuador, the Philippines, Micronesia, and Fiji—already have established relations with the U.S. Coast Guard, making institutional buy-in all the easier.

Looking Forward

IUU fishing is a problem for the entire Departments of Defense and Homeland Security.14 However, the Coast Guard is best positioned to take on the challenge. To make maritime domain awareness (MDA) more robust, the Coast Guard should prototype a simple crowdsourced MDA platform, which does not have the upfront cost of exquisite surveillance assets. Such a platform would improve the Coast Guard’s capability to interdict Chinese IUU fishing, while simultaneously mobilizing local communities. For years, the act of exposing IUU fishing has largely been done by governments and a few specialized non-governmental organizations. The scope of the problem now demands an all-hands-on-deck effort that incorporates simple reporting by concerned and impacted local watermen.

1. U.S. Coast Guard, Illegal, Underreported, and Unregulated Fishing Strategic Outlook, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, September 2020.

2. “Illegal Fishing,” World Wildlife Foundation, 2022, www.worldwildlife.org/.

3. Ian Urbina, “How China’s Expanding Fishing Fleet Is Depleting the World’s Oceans,” Yale Environment 360, 17 August 2020.

4. “U.S. Government and Nonprofit Organization Host Prize Competition to Leverage the Latest Technology to Detect and Defeat Illegal Fishing,” Defense Innovation Unit, 22 July 2021

5. Uday Govindswamy, Planet Labs, interviewed by author, 26 March 2020.

6. Michael Boito, et al., “Metrics to Compare Aircraft Operating and Support Costs in the Department of Defense,” RAND Corporation, 2015.

7. Brendon Providence, Volpe National Transportation Systems Center, U.S. Department of Transportation, interviewed by author, 10 March 2020.

8. Joyce Hufton, Coral Movement, interviewed by the author, 13 December 2020; Yoyong Suarez, IMPL Project, interviewed by the author, 6 June 2020; and Dr. Francisco Buencamino, Tuna Canners Association of the Philippines, interviewed by the author, 25 March 2020.

9. Hunter Stires, “The South China Sea Needs a ‘COIN’ Toss,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 145, no. 5 (May 2019); and 2ndLt Robert German, USMC, “The Other Side of COIN,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 147, no. 2 (February 2021).

10. Anonymous U.S. Army Green Beret, interviewed by the author, 18 December 2020.

11. Drew Harwell, “Instead of Consumer Software, Ukraine Tech Workers Build Apps of War,” The Washington Post, 24 March 2022.

12. CDR Cyrus Mendoza, Philippine Navy, interviewed by the author, 13 January 2021.

13. Marguerite Reardon, “Can Dataless Smartphones Still Use GPS Navigation Apps?” CNET, 13 March 2013.

14. Dr. Joseph Felter, Stanford University, Hoover Institute, interviewed by author, 10 March 2020; CAPT Michael O’Hara, USN, U.S. Naval War College, interviewed by author, 19 June 2020; COL Leo Liebreich, U.S. Army, interviewed by author, 29 May 2020; and CAPT Chris Sharman, USN, interviewed by author, 5 March 2020.