Today, few people recall or know that the United States got into Vietnam through a backdoor labeled “Laos.” The U.S. Navy’s air war began in 1963 with “Yankee Team” reconnaissance flights launched from Tonkin Gulf–based aircraft carriers. Nominally supporting the Laotian government in Vientiane, Washington approved overflights to track the antigovernment Pathet Lao movement, which was allied with Hanoi. The Laotian Communists resented being scrutinized and expressed their displeasure with gunfire.

In June 1964, the Navy lost its first aircraft in Southeast Asia, an RF-8 Crusader off the USS Kitty Hawk (CVA-63). Lieutenant Charles F. Klussmann was captured but escaped at the end of August. By then, the Navy and the nation had gone full-ahead in Vietnam. Two reputed incidents in the Tonkin Gulf gave President Lyndon Johnson the political capital he needed to rally the country behind his election campaign, which was only 90 days away.

On 2 August, North Vietnamese PT boats clashed with two U.S. destroyers supported by fighters from the USS Ticonderoga (CVA-14). No significant damage occurred, but a second alleged clash came two nights later. Present both nights was Commander James B. Stockdale, commanding officer of Fighter Squadron (VF) 51. He knew there were no hostile craft the second night and, after his return in 1973 from six and a half years of captivity in Vietnam, he said, “That war was a bastard from the start.”1

Johnson was elected to a full term that November, and the Southeast Asian war entered a nine-year morass.

Carrier Operations

Seventh Fleet maintained Task Force 77, with aircraft carriers cycling through the western Pacific. Two operating areas were established: Dixie Station off South Vietnam and Yankee Station farther north. Typically, newly arrived ships and air wings broke into combat with missions over the south, where the threat level was far less than up north. U.S. Pacific Command divided North Vietnam into regions called route packages, each generally assigned to the Navy or Air Force. The hot spots were in “Route Pack Six,” (designated VI) with VIA covered by the Air Force out of South Vietnam and Thailand, and VIB by Task Force 77.

Between 1964 and the end of the war in 1973, 17 attack carriers deployed to combat. So did four antisubmarine carriers, although hostile subs did not operate in those relatively shallow waters. During that period, Navy and Marine Corps fixed-wing squadrons lost 1,100 aircraft to all causes in theater, both afloat and ashore. Carriers usually alternated on 12-hour shifts, noon to midnight and midnight to noon. There probably was no greater challenge in tactical aviation than single-plane night missions, for which Grumman’s A-6 Intruder was conceived. The Navy flew 52 percent of its missions into North Vietnam versus 43 percent for the Air Force, which had greater responsibility for other areas of Indochina.

Weather was always a factor in Tonkin Gulf operations, although Vietnam had diverse climates, generally temperate in the north and tropical in the south. Overall, the annual 70 inches of rainfall was concentrated from May to October, with about 60 inches in those six months. A two-tour carrier aviator said, “You’ve not been rained on until you’ve been in a Southeast Asian monsoon.” Some survivors describe penetrating hostile airspace below a 200-foot ceiling with the radar altimeter set for 100. An A-4 pilot recalls, “I flew stepped up on lead’s starboard wing so if he went in we wouldn’t lose both planes.”2

Armed reconnaissance missions—“road recces”—were notorious for the multiple risks of weather, terrain, and enemy action, approximately in that order. A Phantom pilot explained, “Clear air normally resulted in lower losses on Alfa Strikes. When the decision was made to go when the weather was less than ideal, the loss rate was usually higher, which makes sense.”3

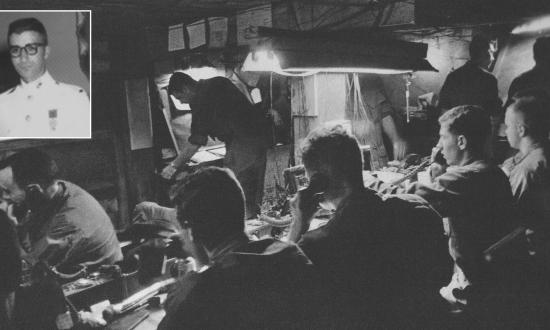

As in all wars, leadership was held at a premium. Tonkin Gulf air wing and squadron commanders usually flew “the rough ones” as a matter of pride and professionalism. “Bad places, good targets” was how many expressed it. More than 100 Navy commanders (O-5s) were killed or captured in those nine years.4 A recurring theme was professionalism, often expressed in the flippant statement, “Sure it’s a lousy war, but it’s the only one we have.” That attitude was stated more formally by Commander John B. Nichols in his analysis-memoir, On Yankee Station: “We had accepted the king’s shilling for years, and now we were expected to pay back the investment. It was not only expected of us; we expected it of ourselves.”5

Morale underwent a years-long evolution, descending from the initial enthusiasm many aircrew felt in 1964–65. As support for the war declined at home, with continual losses for little visible progress, inevitably men at the sharp end began reassessing their situation. During 1968, aircrews noted an unspoken frustration growing in squadron ready rooms. As if by tacit agreement, the emphasis switched from purely mission-oriented considerations to one of mutual concern. “The politicians didn’t quite know what to do with us,” said a three-cruise pilot. With no stated goal from the national leaders, and no end in sight to the war, aviators began to adopt an attitude best expressed as “Let’s watch out for each other.” That shared concern for shipmates appeared in 1985 with A-6 pilot Stephen Coonts’ best-seller Flight of the Intruder. Tellingly, the novel’s original title had been For Each Other.

By the end of the war, attack carriers had lost nearly 700 men from air wings and ships’ companies.

Surface-to-Air Missile Threat

As North Vietnam’s defenses strengthened, so did the need for U.S. countermeasures. Throughout the war, Soviet-supplied surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) received a disproportionate share of public attention in the United States; in fact, about 85 percent of combat losses were the result of antiaircraft fire. But the supersonic SA-2 Guideline missile could force U.S. fliers to descend into Vietnam’s dense flak zones, from 23-mm to 100-mm weapons.

Overall, the United States lost 2,317 fixed-wing aircraft in combat throughout Southeast Asia, with some 205 assessed as SAM kills—roughly 9 percent, including shoulder-mounted SA-7s in South Vietnam.6

Douglas Skywarriors provided electronic support, as EKA-3s could jam enemy radar and communications while a strike ingressed and egressed. On a 1972 mission, a USS Constellation (CVA-64) fighter crew was saved when an “Electric Whale” jammed SAM warhead frequencies. The F-4 pilot’s home-movie camera captured two frames of an SA-2 passing close aboard. In the next port visit, the jammers received a heartfelt gift of adult beverages.

Timing was crucial in evading a missile. Surviving a SAM launch became an exercise in sweaty-palm patience and pulse-pounding judgment. Articulate aviators spoke of the soul-searing experience of dueling with an inanimate object that pursued its prey with almost human intelligence.

But the missile was an aircraft, subject to the same physical laws governing manned aircraft. As an SA-2 approached detonation range, its small wings could not manage the gravitational force of a hard turn. Therefore, smart aviators turned in two planes simultaneously to compound the difficulty of the missile’s tracking. A barrel-roll turn, keeping the SAM 30 to 40 degrees off the nose, was optimum.

The A-6 fulfilled the Navy and Marine Corps all-weather ground-attack/strike mission, including single-plane night missions. Credit: U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

North Vietnam had a third-tier air force that benefited from Soviet patronage. But aside from SAM battalions, Hanoi built a fighter force with subsonic MiG-17s and supersonic MiG-21s, augmented by barely supersonic MiG-19s. With a clear radar picture of the North’s airspace, controllers could vector MiGs onto U.S. formations, usually for “pop-ups” from low and behind the “Yankee Air Pirates” or slashing attacks relying on high speed and air-to-air missiles.

Navy and Marine Corps fighters came in two flavors: Vought’s F-8 Crusader series, mostly on board Essex-class carriers, and McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantoms on “big deck” ships such as the Forrestal-, Midway-, and Enterprise-class carriers. The single-seat F-8 had the war’s best kill-loss ratio, but two-seat F-4s scored the most victories.

U.S. Bombing Campaigns

When President Johnson called a bombing halt in 1968, the overall U.S. fighter kill-loss ratio was barely 2:1. But contrary to the Air Force, the Navy established a fighter weapons school at San Diego, graduating its first class in 1969. By the end of the contest in January 1973, the naval fighter exchange rate was more than 8:1.7

North Vietnam’s air force was too small to prevent U.S. bombing, even when supersonic MiG-21s arrived in 1966. But enemy fighters could force strike aircraft to jettison ordnance to maneuver against “bandits,” a tactical win for the defenders. However, MiG bases remained off limits until 1967 and were sporadically attacked thereafter. Washington’s reasoning was the same as for SAM sites—excessive concern about killing Soviet personnel. In fact, no missile battery was struck until after the first SA-2 kill of an Air Force F-4.

Limitations on striking SAM and MiG targets were only part of Washington’s onerous rules of engagement. They stood for most of the war, with rare exceptions granted by the White House before 1972. Air Force Colonel Jack Broughton expressed the attitude in Going Downtown: The War against Hanoi and Washington (Crown, 1988).

For most of the war, Hanoi and Haiphong—the critical areas in Pack Six—were off limits, as was the Chinese border. Sometimes when worthwhile targets were approved, Washington micromanaged aircrews, such as specifying dive headings on bridges. Aviators had known since World War I that the way to bomb a bridge was diagonally along the span. A perpendicular approach—avoiding people at either end—made accuracy almost impossible.

Yet, among the thousands of sorties carrier aircrews flew “up North,” two evolutions stand out. In late March 1972, Hanoi launched its “Easter Offensive,” intended to conquer South Vietnam once and for all. Four days later, President Richard Nixon loosed the bombers in response, and TF-77 fliers scored notable victories within days.

On 9 May, the USS Coral Sea’s (CVA-43) Air Wing 15 began the years-delayed mining campaign against North Vietnamese ports and waterways. Flying low, nine of Commander Roger Sheets’ A-6 Intruders and A-7 Corsairs dropped 36 time-delayed mines in Haiphong’s harbors—the bow wave of thousands of “weapons that wait” dropped over the next seven months. The Navy and Marine Corps crews got away clean.

Five months later, the USS America’s (CVA-66) Air Wing 8 wrote the final chapter in the seven-year saga of Thanh Hoa Bridge. “The Dragon’s Jaw” was a symbol of Hanoi’s resilience, feeding one of the main supply routes from the North to the Demilitarized Zone. Navy and Air Force squadrons had flown hundreds of sorties against the edifice, to no lasting effect until 1972.

On 6 October, four VA-82 Corsairs led by Lieutenant Commander Leighton Smith slew the dragon with precision-guided ordnance and “dumb” bombs. Combined with prior damage from Air Force fighters, Thanh Hoa Bridge was out of business for the duration.

Unheralded but Vital

Carrier operations could not have been conducted as they were without in-flight refueling. Rear Admiral James D. “Jig Dog” Ramage said, “Tanker fuel is the most expensive because you pay for it twice but when you need it, you really need it!”

Dedicated tankers were the province of Douglas KA-3 Skywarriors, big twin-engine types from master wingsmith Edward H. Heinemann, who also designed the A-4 Skyhawk. The “Whales” took up a good deal of deck space but repeatedly proved their value. Fighter and attack pilots deeply appreciated tanker crews, who sometimes ignored orders against going “feet dry” to pump lifesaving JP-5 into a starving strike aircraft.

When KA-3s were unavailable, attack squadrons provided “buddy pack” refueling on a smaller scale via A-4 Skyhawks, A-6 Intruders, and A-7 Corsairs.

Photographic intelligence was the realm of Vought RF-8 Crusaders and North American RA-5 Vigilantes. “First in, last out” was their motto, often earned with high losses. The super-sleek “Viggie” looked like it was going 400 knots sitting on deck and was so fast that it could outpace its burdened F-4 escorts.

Other Players

A perennial player in “The Tonkin Gulf Yacht Club” was Navy Helicopter Combat Support Squadron (HC) 7, the dedicated air-sea rescue unit flying Kaman UH-2s, Boeing-Vertol UH-46 Sea Knights, and Sikorsky HH-3 Sea Kings. Between 1967 and 1973, the HC-7 “Big Mothers” cycled detachments through a variety of carriers and surface ships, rescuing 149 people, 79 in combat. Spirited Big Mother crews placed posters on their bulkheads: “When you’re down in the water and the sampans are coming to get you, call for a Phantom to pick you up.”

While carrier-based units received most of the attention, land-based naval air also contributed. Twenty or more patrol squadrons with P-5 Marlins, P-2 Neptunes, and P-3 Orions flew Operation Market Time interdiction missions along South Vietnam’s 1,200-mile coast. Meanwhile, two Navy squadrons flying UH-1 Hueys and OV-10 Broncos supported riverine forces.

Three Marine Corps fighter squadrons deployed with Tonkin Gulf air wings—VMFA-212 (Oriskany) in 1965, plus VMFA-333 (America) and VMA(AW)-224 (Coral Sea) in 1972. Meanwhile, shore-based flying leathernecks were early players, with Sikorsky H-34 squadrons arriving from 1962 to 1964. Subsequently, three Marine air groups with about two dozen helicopter units rotated through Vietnam between 1965 and 1971. With the U.S. force buildup, three Marine air groups with ten fighter and ten attack squadrons served from 1965 to 1970.8

Little heralded were Coast Guard aviators who logged Air Force exchange tours in C-130 Hercules and HH-3 helicopters.9

Whatever their time or station during the Vietnam War, naval aviation veterans retain their pride in serving.

1. VADM James B Stockdale, USN (Ret.), to author, 1983.

2. CDRs R. R. Powell, USN (Ret.), and Jack Woodul, USNR (Ret.), to author May 2021.

3. CAPT Lonny McClung, USN (Ret.), to author, May 2021.

4. American War Library, The Names of Vietnam War Personnel 1945 to 1975.

5. John B. Nichols and Barrett Tillman, On Yankee Station: The Naval Air War Over Vietnam (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1987).

6. John T. Correll, “The Air Force in the Vietnam War” (Arlington, VA: Aerospace Education Foundation, 2004).

7. The usually quoted figure is 12:1 because at the time some losses were unknown.

8. Keith B. McCutcheon, “Marine Aviation in Vietnam 1962–1970,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 97, no. 5 (May 1971): 122–55; “USMC Vietnam Order of Battle.”

9. William H. Thiesen, “The Coast Guard in Vietnam—A Remembrance,” My CG, 26 March 2021.