Early on the morning of Sunday, 11 June 1972, I was assigned to fly a MiG combat air patrol (CAP) mission from the aircraft carrier USS Coral Sea (CVA-43) as wingman for the commanding officer of Fighter Squadron (VF) 51. Not long before, I had been placed “in hack,” which resulted in temporary suspension of my flight leader qualifications. I was ordered to fly only as a wingman with the skipper, executive officer, maintenance officer, or operations officer, but, on a positive note, I got some great missions flying with the “heavies.” (I had flown a Phantom without a radar-intercept officer or wingman from NAS Cubi Point, Philippines, to the Coral Sea. As I was handing out mail in the squadron ready room, the ship’s captain asked my skipper why I had landed single-seat. Thus busted, I was sent to my room.)

On 11 June, our section of F-4B Phantom IIs—the skipper, Commander Foster “Tooter” Teague, with his radar-intercept officer, Lieutenant Ralph Howell, and me with Lieutenant Don “Puppy” Bouchoux—were assigned to place ourselves between Hanoi and Thanh Hoa in North Vietnam to protect a strike group from air-to-air threats while it was bombing Nam Dinh.

Vietnam. The image dates to 1966.

The skipper and I launched, rendezvoused, and completed our combat checklists before going “feet dry”—crossing the beach and operating over land. We each had four infrared-guided Sidewinder (AIM-9) missiles and two radar-guided Sparrow (AIM-7) missiles. Our radar was not functioning, so the Sparrows were useless.

We ingressed in combat-spread formation at 5,000 feet above ground level (AGL) to protect each other’s six-o’clocks (the position directly behind the aircraft, where we were most vulnerable to attack) and to maneuver easily. We had just arrived at our predetermined CAP position, when the flight controller, call sign Red Crown, gave our flight a vector of 040 degrees (northeast). Unfortunately, Puppy and I did not hear the instructions, as our radios were intermittent. But we could see the skipper was going someplace fast, so we jumped on his starboard side in combat spread—abeam and level with him, about a mile off his starboard wing.

Keeping my head on a swivel, I looked up to see four silver MiG-17 Frescos—they were beautiful! I said, “Puppy, the fight is on.”

I had always told myself, if given the choice: Go for the leader. If you get him, the others will probably scatter. Puppy and I had to barrel roll to the outside to give us more nose-to-tail behind the skipper. The lead MiG dived onto the skipper and was closing to about 500 feet to open up with his guns. But by this time, we were very low! The roll got my attention as the ground appeared just above my canopy. I brought the nose of my Phantom to the lead MiG’s tailpipe, about 20 degrees cold and half a mile in trail. The MiG’s tailpipe was just outside of my gunsight. I had intentionally turned down my aural missile tone during my combat checks, as I did not want the tone to obliterate any voice transmissions (although it turned out not to matter anyway, as we were NORDO—no radios).

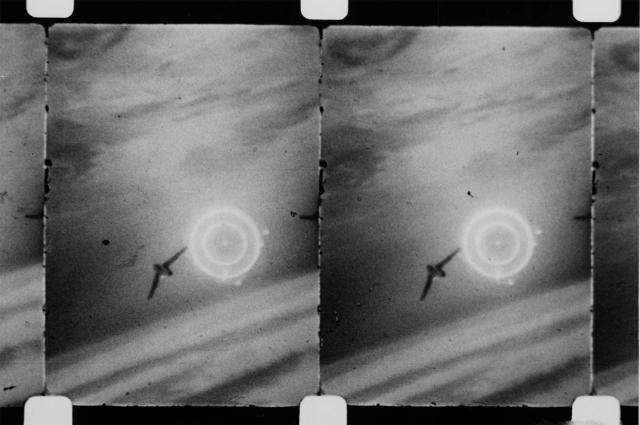

I had my switches selected to fire the heat-seeking Sidewinder, so I squeezed the trigger. It seemed like an eternity before that missile left the airplane. The Sidewinder tracked way to the inside (pulling lead) on the MiG, so I thought I had missed! All of a sudden, the missile took a hard left turn and hit the Fresco in the center, cutting off both wings at the fuselage. It was a huge explosion. The MiG went straight into the ground—the pilot had no chance to eject. I pulled up immediately to miss the fireball and not ingest anything into my engines or get hit by the debris.

While Puppy and I were engaged, the skipper and Ralph were chasing the leader’s wingman. They fired three Sidewinders and finally got him.

After pulling up, I rolled back down to chase MiGs 3 and 4, who were escaping back to Hanoi (Gia Lam Airfield). They were approximately two miles in front of me. While I could have caught them and “smoked two more,” I could not leave my wingman unattended. Since I couldn’t talk to the skipper, I had to take my eyes off the MiGs and look for him. He came into view quickly, but when I returned to the MiGs, they were gone. (I have lost some sleep over that decision, but it was the right thing to do).

The skipper and I orbited the two crash sites (his MiG and mine) for just a minute, then commenced our egress. The strike group had finished its work at Nam Dinh; two MiG-21s were now being vectored our way.

We exited very low, no more than 200 feet AGL. Unfortunately, it wasn’t low enough! The “fire warning light” came on inside my cockpit. In the F-4, these lights were normally good indicators that we were on fire. My radios started to work again, and we mentioned to the skipper that we had a port-engine fire light. Tooter came alongside and told us we were definitely on fire.

Puppy talked about ejecting, but I did not want to be a prisoner of war in North Vietnam. I told Puppy the Phantom was flying okay, and we would eject when the airplane blew up. He said, “You’re an idiot. If it blows up, we’ll be dead!” I said, “In that case, we won’t need to eject.”

When we were over the water, I shut down the port engine. The Coral Sea would not permit us to land, as we were streaming black smoke. Once the rest of the air wing’s aircraft had landed, we were given permission to trap—the smoke had dissipated. The flight deck crash crew covered us with foam, and Puppy and I crawled out, very thankful to be home.

The fire had been so intense that it had welded one of our Sparrow missiles to the fuselage. Why it never exploded, I don’t know—maybe God had other plans for us! That Phantom never flew again. Today it sits on a pedestal in front of the Veterans of Foreign Wars post in Hinsdale, New York; Puppy and I attended the ceremonies for its presentation and told them our story.