Russian submarine activity in recent years has increased to levels not seen since the Cold War. In addition to the quantity of Russian activity is the quality of the new Russian guided-missile submarine (SSGN) Severodvinsk, which Admiral James Foggo, commander, U.S. Naval Forces Europe, described as “very capable and . . . very quiet.”1 On the other side of the world, the Chinese Navy recently surpassed the U.S. Navy in ship numbers. The undersea competition against both adversaries will intensify in the next decade, when the United States decommissions many of the Los Angeles–class fast-attack nuclear submarines (SSNs) built in the 1980s and 1990s.2

A historical look at the Cold War offers useful perspectives regarding antisubmarine warfare (ASW) prioritization, weapon development, and the challenges of facing a peer adversary. And even though much of U.S. Cold War ASW operations remain classified, there are still applicable, unclassified lessons worth highlighting.

Prioritizing Antisubmarine Warfare

Shortly after the Second World War ended, Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Chester W. Nimitz designated ASW as one of the Navy’s top two priorities, along with the brand new threat of nuclear warfare.3 When the Korean War caused Congress to quadruple defense spending—which historian Owen R. Coté called “a necessary but by no means sufficient step towards fashioning a new ASW response to a much greater threat”—the Navy therefore already was beginning to attack the problem.4

With ample funding, the Navy capitalized on captured German sonars and collaborated with premier institutions such as Bell Labs, Columbia’s Hudson Lab, the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution to improve acoustic theory and rapidly develop sonars of increasing antenna gain and processing power. The sound surveillance system (SOSUS) on the seafloor was one result, alongside improvements to passive sonars on submarines, surface ships, and aircraft-dropped buoys.5

These advances helped the U.S. Navy realize how vulnerable its own submarines were to acoustic detection, particularly the new, nuclear-powered submarines. Consequently, submarine designers sought to make their boats quieter, while sonar designers sought to find more acoustic vulnerabilities. This cycle proved incredibly expensive, but early and energetic pursuit of both kinds of improvement established a commanding lead the Soviets did not close for decades.6

Staying ahead of the Russian and Chinese submarine threat in the 21st century requires a similar recognition that ASW needs to be ranked as one of the Navy’s top priorities. This is more than semantics: Capable ASW requires significant investment. Winning undersea great power competition requires rebuilding the sort of shore- and sea-based infrastructure that the United States and its allies possessed during the Cold War: maintenance facilities, trainers, and shore staffs that can allow warfighters to focus on their mission. Recommissioning Second Fleet is a good start, but more needs to be done.

An Unspoken Weakness

Despite its impressive sensors and quiet propulsion, the U.S. Navy submarine force had an Achilles’ heel through much of the Cold War: torpedoes.

The submarine force deployed its first homing torpedo, the 16-knot Mk 27, at the end of World War II. The 26-knot Mk 37 followed in 1956, adding wire guidance in 1960. These torpedoes were designed to attack snorkeling submarines that went no faster than 8 to 12 knots. But with the advent of nuclear propulsion, the United States soon faced Soviet submarines capable of 30 knots, faster than the Mk 37. As a result, the Navy issued technical requirements in 1960 for a new high-speed ASW torpedo. After a development filled with delays, the Mk 48 torpedo finally reached the fleet in 1972; astonishingly, the United States had no conventional torpedo capable of catching a Soviet submarine running at high speed for 14 years! Until the Mk 48, the submarine force instead relied on nuclear-tipped weapons such as the Mk 45 torpedo and the UUM-44 submarine rocket. Submariners also planned to rely on their acoustic advantage to get close to Soviet submarines and shoot them with slow Mk 37s from a position where the torpedo launch either would not be detected or would leave the Soviet submarine no time to evade.7

To be fair, the prolonged development of the Mk 48 was not unique. The Royal Navy had an even more difficult time developing a modern ASW torpedo. It did not field the Mk 24 Tigerfish until 1974, and even then, it had doubts about the torpedo’s ability to sink advanced Soviet submarines.8

The lesson for today’s Navy is that submarine-launched weapons—particularly conventional warhead ASW weapons—are challenging and time-consuming to develop. As a result, the U.S. Navy must urgently assess its current weapons and assign requirements for the next generation of ASW weapons. This should be one of the highest engineering priorities for today’s Navy.

Blind Man’s Bluff

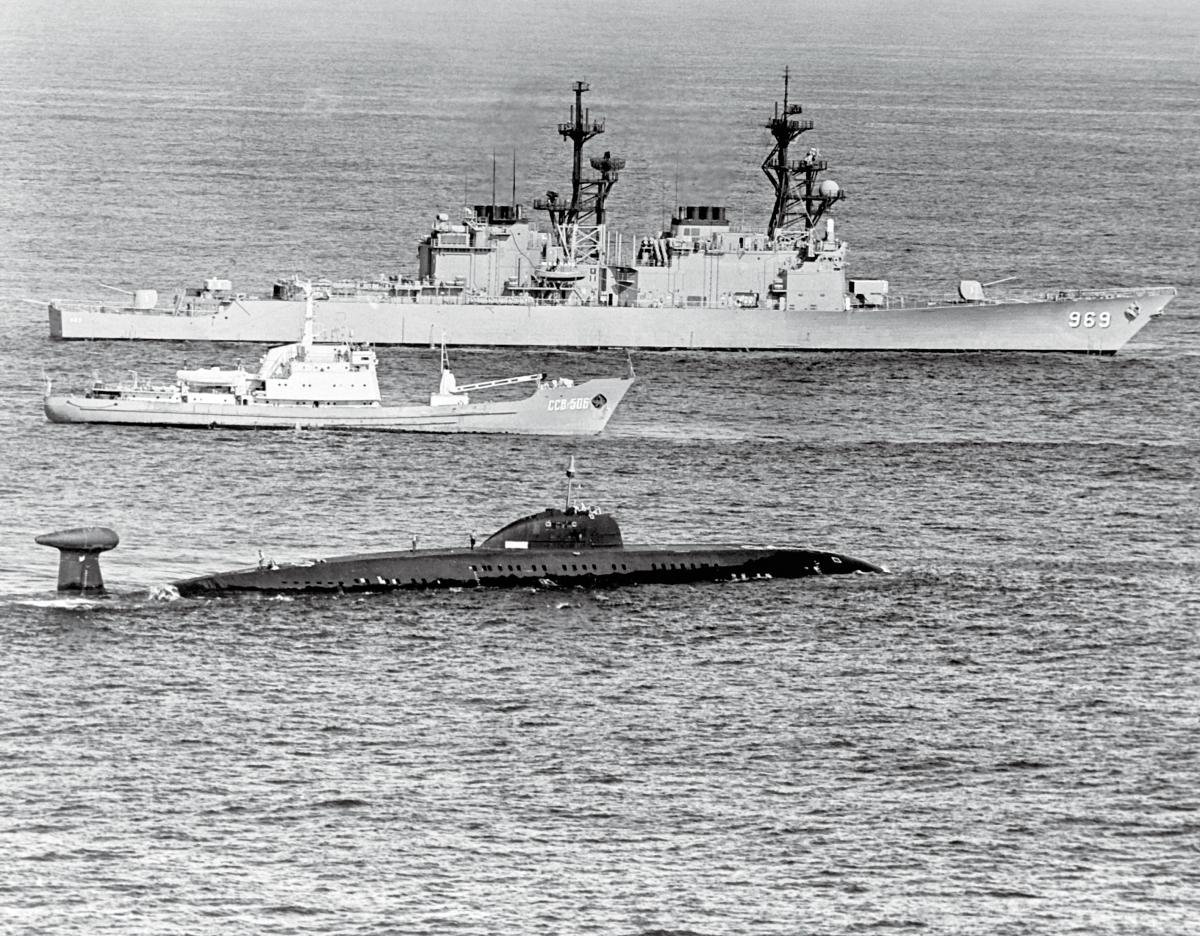

Just as the United States and the United Kingdom finally fielded viable conventional ASW weapons, the Soviets commissioned the Victor III–class nuclear-powered attack submarines (SSNs), which possessed disconcerting acoustic advances that threatened U.S. and British undersea superiority. The class’s quieting resulted from superior manufacturing technology illicitly acquired from Norway and Japan. New tactics also played a role: The Soviets started to operate older, noisier submarines near SOSUS arrays to mask passage of newer, quieter submarines. The reason for these dramatic changes became clear after the 1985 arrest of Navy warrant officer John A. Walker, who had been passing priceless intelligence to the Soviets since 1967.9

It would be difficult to overstate how devastating Walker’s treason and the acquisition of the quieting technology were. In the early 1980s, the Soviets fielded the titanium-hulled Sierra-class SSN, based in large part on advances resulting from Walker’s information. The Soviets simultaneously built the larger steel-hulled Akula-class SSNs that incorporated even more quieting technology. By the end of the Cold War, numerous incidents had illustrated the quality of the new generation of Soviet submarines.10

In March 1987, for example, the Soviets deployed five Victor IIIs in the North Atlantic simultaneously, prompting a massive ASW response by the United States and the UK: “The search was so intensive and so demanding that the RAF’s Nimrods used their entire yearly supply of sonobuoys in the space of a few weeks.”11 Although the two navies were able to track four of the five Victors almost continuously with SOSUS, surface ships, submarines, and aircraft, the fifth Victor turned out to be more quiet and skillfully commanded. HMS Trafalgar, the lead ship of the then-latest class of British SSNs, tracked the fifth Victor and was forced to accept repeated close-quarters situations to maintain contact.12 Two years later, “[i]n October 1989, a Yankee I, two Delta Is, a Delta II, a Delta III and a Delta IV were all unlocated, and a Victor III that had been held on SOSUS operating north of Bear Island simply disappeared.”13

The growing Soviet capabilities were justifiably concerning. U.S. Admiral Kinnaird McKee, director, Naval Nuclear Propulsion (1982–88), summarized this threat when he famously said, “Eventually, U.S. and Soviet submarine capabilities will converge. . . . It will be blind man’s bluff with other submarines.”14

Quantity of Quality

But the growing Soviet threat was not as overwhelming as it appeared. For one thing, the expense in making and maintaining these quality submarines meant that the Soviets could only build a handful. In 1989, the Soviets possessed an astonishing 349 submarines. But only 35 were the latest SSNs/SSGNs: 5 Oscars, 4 Akulas, 1 Mike, 2 Sierras, and 23 Victor IIIs. These 35 Soviet submarines faced 90 peer adversaries: 5 British Trafalgars, 41 Los Angeles class, and 37 Sturgeons, as well as one-of-a-kind ASW submarines such as the Glenard P. Lipscomb (SSN-685) and Narwhal (SSN-671).15

More important, the United States and Great Britain also possessed a qualitative advantage in personnel. Both the U.S. and Royal Navies maintained all-volunteer submarine forces that benefited from sustained at-sea experience and superb training. The Soviet Navy, by contrast, depended on conscription and automation to man its larger force. As a consequence, it did not go to sea as often and did not develop as deep a set of skills as U.S. and British submariners. This gap was highlighted when the Soviet Mike-class submarine Komsomolets sank in 1989. Reviewing the disaster, her assistant chief designer wrote:

Analysis of the crew’s actions during the accident revealed its total inability to fight for the submarine’s survival. Weak combat and occupational training of the crew, specifically their unfamiliarity with ship systems, emergency procedures, and life-saving equipment, led to the tragic outcome of the accident aboard the submarine Komsomolets.16

In short, the United States and Great Britain actually had a quantitative, not merely qualitative advantage: On any given day, they could surge more quality submarines with more quality crews than the Soviets. The United States and Great Britain highlighted this quantity of quality with the “forward diversion” strategy and coordinated ASW.

The forward diversion strategy, commonly associated with the U.S. Navy’s 1986 Maritime Strategy, involved U.S. and British submarines operating north of the Greenland–Iceland–United Kingdom (GIUK) gap to find and put Soviet nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) at risk. In response, the Soviets withdrew their best SSNs from the Atlantic to protect their SSBNs. This strategy had flaws, but it helped shift the costs of ASW onto the Soviets.17

In addition, the U.S. Navy revisited “cooperative” ASW tactics, which largely had been abandoned in the 1960s because of improvements in passive acoustics.18 The renewed focus on coordinated ASW forced interaction between the Integrated Undersea Surveillance System (IUSS), submarines, destroyers, embarked ASW helicopter units, and maritime patrol/reconnaissance aircraft. Ultimately, these teams conducted peacetime ASW and tracked down Soviet submarines in the open ocean.19

The concepts behind a quantity of quality, forward diversion, and coordinated ASW remain valid. Russia and China both rely on annual conscription, although each navy has a sizable enough professional cadre to either mitigate the conscripts’ presence or even avoid sending them to sea.20 But in terms of the quantity of skilled submariners and the numbers of submarines, it appears the United States and Great Britain maintain a lead. Russia currently has 27 SSN/SSGNs, while China has at least 6 SSNs. Against this the United States still has 51 SSNs and Great Britain has 7.21

Maintaining the quantity of quality, however, requires intensive and relentless focus on training and qualifications. This imperative depends on rebuilding the infrastructure of the Cold War. Other authors have written about competing priorities that detract from adequate training, such as maintenance, lack of trainers, and administrative programs. To let warfighters prepare for war, maintenance facilities need to take the lead in maintenance, schoolhouses need to provide more trainers, and immediate superiors in command must provide presence and assistance. With such infrastructure in place, the priority for ASW operators, in port and at sea, should be rigorous warfighting training and qualification.22

Lessons to Be Learned

A historical perspective can blunt the onset of fear. For example, the Severodvinsk may be both capable and quiet, but so were the Victor IIIs, Sierras, and Akulas in the 1980s. And China may be building slightly more than two submarines per year, but that is nothing compared with the Soviet Union’s peak production rate of a submarine every six weeks in the 1980s, a rate of construction all of NATO could not compete with. (At the time, the British worried they would run out of torpedoes before the Soviets ran out of submarines.) Despite these challenges, Navy leaders and ASW operators recognized their strengths and devised strategies and tactics to compete.23

But the Navy has not written a classified history of Cold War ASW operations. Officially sanctioned but unclassified histories—such as Owen Coté’s The Third Battle (2003) or Peter Hennessy and James Jinks’s The Silent Deep (2015)—are well-written and remarkably candid, but Coté noted that “as an unclassified discussion, [The Third Battle] has by necessity left out much that is relevant to the Cold War ASW story.”24 He recommended:

The Navy should have a great interest in sponsoring rigorous historical studies of these areas at whatever classification level is necessary in order to preserve its institutional memory of events now often residing only in the individual minds of a shrinking cadre of actual participants.25

In 2019, that need has only grown. The full lessons of Cold War ASW operations cannot be captured in a brief article, especially an unclassified one. And while the Navy should not wait to combat the 21st-century Russian and Chinese submarine threats, a full accounting of the lessons learned from the Cold War would help guide the Navy’s ASW focus in the coming years. Consequently, the Navy should commission a classified history of ASW operations during the Cold War for fleet consumption.

These are challenging but exciting times. The history of the Cold War tells us the U.S. Navy—the entire Navy, not just the submarine force—should prioritize ASW. Without ASW, the nuclear deterrent and the Navy’s ability to project power could both be at risk. The submarine force should learn from its difficulties developing the Mk 48 torpedo to urgently fund and develop next generation ASW weapons. Last, it is wise to remember that the challenge posed by the Russian and Chinese submarine fleets is not fundamentally new. As the Navy looks to the future of ASW operations facing old and new great power rivals, it is clear much remains to be learned and applied from the lessons of Cold War ASW.

1. David Martin, “How NATO and the U.S. Are Preparing for Any Russian Aggression off the Coast of Norway,” CBS News, 28 April 2019; Sam LaGrone, “Admiral Warns: Russian Subs Waging Cold War-Style ‘Battle of the Atlantic,’” USNI News, 2 June 2016.

2. Scott Truver, “A Not-so-simple PLAN?” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 145, no. 8 (August 2019): 10.

3. Owen R. Coté, The Third Battle: Innovation in the U.S. Navy’s Silent Cold War Struggle with Soviet Submarines, Naval War College Newport Papers 16 (Newport: Naval War College Press, 2003), 14; VADM James R. Fitzgerald and RADM Richard F. Pittenger, USN (Ret.), “ASW: Will We Ever Learn?,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 145, no. 4 (April 2019): 59–60.

4. Coté, The Third Battle, 19.

5. Coté, 16–17, 51, 56; Fitzgerald and Pittenger, “ASW,” 61.

6. Coté, 48, 72; Fitzgerald and Pittenger, 61.

7. Coté, 21, 30–31, 57–59.

8. Peter Hennessy and James Jinks, The Silent Deep: The Royal Navy Submarine Service since 1945 (London: Allen Lane, 2015), 304–7, 371–72, 574.

9. Hennessy and Jinks, The Silent Deep, 547–55.

10. Coté, The Third Battle, 69–70.

11. Hennessy and Jinks, The Silent Deep, 565.

12. Hennessy and Jinks, 564–68.

13. Hennessy and Jinks, 576.

14. Coté, The Third Battle, 70–71.

15. Coté, 72; Captain Richard Sharpe, RN, ed., Jane’s Fighting Ships, 1989–1990, 92nd ed. (Frome: Jane’s Information Group, 1989), 556, 563–69, 655–56, 700–4.

16. D. A. Romanov, Fire at Sea: The Tragedy of the Soviet Submarine Komsomolets, ed. by K. J. Moore, trans. by Jonathan E. Acus (Washington: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006), 183; see also: Hennessy and Jinks, The Silent Deep, 8–9, 384, 589–90.

17. Coté, The Third Battle, 64–65, 70–73; Hennessy and Jinks, The Silent Deep, 553–59.

18. Coté, 70.

19. Coté, 76–77.

20. U.S. Navy, The Russian Navy: A Historic Transition (Suitland, MD: Office of Naval Intelligence, 2015), 39, 42; U.S. Navy, The PLA Navy: New Capabilities and Missions for the 21st Century (Suitland, MD: Office of Naval Intelligence, 2015), 27–28.

21. Hennessy and Jinks, The Silent Deep, 589–90; U.S. Navy and Russian Federation Navy Submarine Infographics, Naval Analyses; Truver, “A Not-so-simple PLAN?,” 10.

22. LT Jeff Vandenengel, USN, “A Deckplate Review: How the Submarine Force Can Reach its Warfighting Potential, (Parts 1 and 2)” Center for International Maritime Security, 30 April 2018 and 14 May 2018.

23. Hennessy and Jinks, 516–17, 545–59; Coté, The Third Battle, 69–78.

24. Coté, 90.

25. Coté, 90.