This year marks the 75th anniversary of the U.S. victory in World War II. In the Pacific theater, that victory was earned on the high seas—in storied submarine combat patrols that held the line after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, hard-fought naval battles that broke the back of the enemy, and an amphibious campaign that wrested control of key points on the march to final victory.

Reflecting on the outcome of World War II, it is easy to lose sight of the fact that, in the years leading up to the war, the United States was embroiled in a heated race with Japan and Germany—two countries with impressive industrial capacity, engineering expertise, and military professionalism and commitment. The country was facing great power competition, and the prospect of success in a maritime conflict was far from certain.

Yet, the nation’s response enabled the U.S. Navy to master the seas and overcome capable and determined opponents. The United States mobilized academia and industry to design and build a world-class Navy to support U.S. Allies and take the fight to the enemy across two oceans. It introduced innovations such as radar, naval aircraft strikes, and communication code breaking, and it assembled a generation of sailors aligned to a common and just cause and empowered them to win.

Maritime War in an Era of Great Power Competition

Today, the United States once again is in a great power competition with potential foes who seek to reshape the world order and diminish U.S. and allied influence and access. China is now capable of challenging the U.S. Navy for sea control in the Pacific, and the Russian Navy has the ability to disrupt control of the Atlantic. To address these rising challenges, the U.S. Navy is returning to its roots: pivoting from its recent focus on power projection ashore in support of regional conflicts to a focus on major war at sea against modern, well-trained naval forces in highly contested environments. Success will require a force that can preserve worldwide maritime access, protect internationally recognized territorial and economic boundaries, and deter major war through combat power and strong and enduring alliances and partnerships.

In major combat scenarios, the adversary is expected to take early and aggressive action across all warfare domains to deny the U.S. Navy access to the battlespace and limit its freedom to maneuver. This includes a web of air-defense systems to deny access to U.S. aircraft and an array of antiship ballistic and cruise missiles to keep carrier strike groups and surface ships beyond effective engagement ranges. Opponents will use space and cyber warfare to degrade U.S. command, control, and communication systems.

Fortunately, the United States retains a clear advantage in the undersea domain. Submarines are not impeded by air-defense systems or antiship ballistic and cruise missiles. Their stealth allows early and lethal access to the adversary’s near seas and shoreline and sows uncertainty in the adversary’s war plans. This is why the Navy continues to build and deploy stealthy, nuclear-powered submarines and why it is now integrating unmanned undersea vehicles (UUVs) and a range of seabed capabilities that extend their reach and effects. In the event of conflict, U.S. submarines must be ready to conduct offensive operations off the adversary’s coast in waters saturated with air- and surface-defense radars and weapon systems. Their mission will be to deny adversaries the use of the seas and to destroy the warships, submarines, and missile systems that impede U.S. sea control and freedom of navigation.

The Role of the Submarine Force

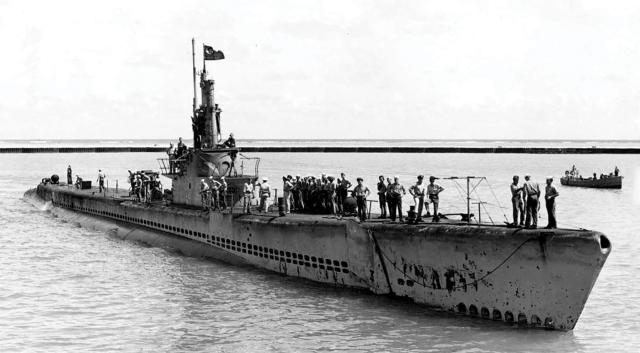

During World War II, U.S. submarines were key contributors to victory in the Pacific theater. Consider the exploits of the USS Bowfin (SS-287) on her sixth war patrol:

She was patrolling near Minami Daito Jima, approximately 200 nm east of Okinawa in the Northern Philippine Sea when she gained contact on a convoy of Japanese ships entering a small landing area with a single pier, a crane and a cache of supplies. During Bowfin’s reconnaissance of the harbor, she identified two merchant ships and a warship escort at the landing area. After firing six torpedoes from two positions within the tightly constrained harbor area, she not only destroyed the targeted vessels but also the pier, crane and a bus.1

The Bowfin’s stealth enabled this operation far forward in the Philippine Sea—waters in which no other U.S. warships could freely venture because of the density of Japanese warships and air power.

Seventy-five years later, the submarine force still relies on that stealth to enable it to operate inside the adversary’s defensive perimeter, but the submarine has evolved from a relatively simple submersible torpedo boat to a multimission nuclear-powered warship bristling with offensive firepower and advanced sensors and communications systems. Today’s submarines have the capabilities and endurance to conduct a much broader range of peacetime and combat missions. In the next few years, the role of the nuclear-powered submarine will expand further, as it becomes a host platform for unmanned and remotely operated underwater vehicles to extend sensor and weapons reach and lethality.

The U.S. submarine force deters strategic attacks every day, with powerful and quiet strategic ballistic-missile submarines continuously patrolling the seas. Likewise, the stealth, endurance, and firepower of its forward deployed fast-attack submarines deter aggression against the United States and its partners and allies. If deterrence fails, U.S. submarines will be the first warships to the fight. They will gain access to the battlespace, blunt the adversary’s attack, and deny its use of the seas through antisurface warfare (ASuW), antisubmarine warfare (ASW), and offensive mining. U.S. submarines also will help set the conditions for joint military access through maritime precision strikes, seabed warfare, and special operations support. Finally, as the Navy and joint forces flow forward to establish air and sea control, those same undersea forces will support the deployment, logistics flow, and offensive operations of U.S. combat forces across the seas.

As competitors expand their military capabilities to challenge U.S. access, submarines operating “alone and unafraid” may not produce the kill rate necessary to achieve the required effects. The United States must increase integration across the joint force to enhance battlespace awareness, improve joint targeting, and participate in closely synchronized joint operations—in some cases employing the submarine as the sensor, in others as the shooter.

Picture an engagement in which a U.S. submarine, operating in coordination with a carrier strike group, provides over-the-horizon targeting to enable a massive long-range antiship cruise missile attack to defeat an amphibious invasion. Alternatively, a stealth aircraft may reconnoiter a maritime operating area and transmit the surface picture to a submarine to conduct a long-range antiship missile and torpedo attack. The ability to work closely with other stealth platforms—including fifth-generation combat aircraft, special operations forces, and space forces—to maximize kill rates will be essential to sea denial in the early phases of maritime warfare.

Preparing for Great Power Competition

In recent years, the focus of submarine combat training has been modified to increase the level of difficulty, recognizing that crews must improve individual skills and teamwork to prevail against a committed and capable adversary.

A submarine crew stepping into a shore-based trainer today experiences a control room that is configured in every detail to mimic their submarine attack center, with optical periscope controllers, sonar, fire-control, and navigation stations configured precisely to match the layout and functionality on the submarine, and with environmental models and adversary ship, sub, and aircraft that look, sound, and shoot with impressive realism. In fact, for some of the most challenging warfighting certification events, squadron commodores choose to observe their crews operating in shore-based trainers versus at sea to leverage the ability to push the complexity and pace of the scenario.

Consider a nighttime ASuW attack against an amphibious landing group consisting of more than 20 surface warships and amphibious landing craft, surrounded by hundreds of fishing vessels and protected by a ring of diesel submarines. It would be nearly impossible to marshal these forces for a submarine certification event, yet in the trainer, crews can run through this scenario in the morn-ing, then return from lunch to run a head-to-head ASW attack against a fellow crew by linking two separate at-tack trainers.

The realism and environmental modeling for ship-board trainers has been substantially improved, and a recently established “aggressor squadron” now trains crews and instructors on adversary capabilities and tactics. Opportunities for structured head-to-head and scenario-based ASW and ASuW training have been incorporated as well, to add the element of competition to shore-based training events. Competition incentivizes innovation in tactics and penalizes risk-averse commanding officers, because the attack team’s success is not measured by how well they followed the tactics but by whether they destroyed the enemy and lived to tell it.

Competitive training also accelerates tactical development. When mission success and survival are the only metrics, submarine crews become passionate about tactics. More important, commanding officers become more willing to cast aside ineffective tactics and adapt to the scenario and the ever-changing foe. This builds more tactically proficient and adaptive attack teams and more decisive commanders. It also sends a demand signal for better tactics. With this in mind, the submarine force is improving the responsiveness and pace of tactics development at training centers and the Undersea Warfighting Development Center.

Maintaining Undersea Dominance

The Navy’s force structure assessments demand a large number of submarines. However, U.S. industrial capacity has shrunk, and there is little prospect for significant near-term expansion in nuclear submarine shipbuilding. Targeting the modernization of Los Angeles- and Virginia-class subs can provide a bridging strategy to grow undersea lethality. This strategy must include investments in stealth, sensors, and weapon systems that enable each submarine to achieve more—higher kill rates, longer and more lethal reach, and more options to deliver effects through offensive mines, UUVs, and special operations forces capabilities. The Navy also must pursue a range of small, medium, and large unmanned undersea systems and submarine-launched unmanned aerial vehicles to extend sensor ranges, better detect and defeat mines, and act as communications nodes and weapon systems.

The Navy also needs to put tools in the hands of sailors faster—let them use them, break them, and establish what works and what does not—then decide whether the tools merit broader acquisition. This is not without risk, but not adopting new technology faster than U.S. opponents poses greater risks.

The Future

The future of the submarine force is not just about new capabilities and improved warships and weapons. It encompasses a fighting force in which each sailor is required to operate at his or her highest potential. It demands a commitment to competency and professionalism from every sailor and civilian. It requires close teamwork, disciplined tactics forged from realistic, challenging combat exercises, and an unshakable foundation in the Navy core values of honor, courage, and commitment.

Finally, as the United States seeks to integrate the capabilities of its undersea forces within a maritime coalition, it must continue to build enduring relationships with allies and partners that allow the coalition to deter, defend, fight, and win together. This can be accomplished through coalition exercises, port visits, and engagements that refine tactics so that all coalition members grow stronger together.

Reflecting on the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II and the lessons from that victory, it is clear that the U.S. submarine force must continue to adapt and transform as the character of maritime conflict evolves. Today, as in World War II, the submarine force will be the first to the fight, and its ability to win depends on how well the United States maintains undersea dominance across tactics, capabilities, and the training and commitment of its sailors.

1. USS Bowfin Submarine Museum & Park, “USS Bowfin History: Patrol 6,” bowfin.org/patrol-6.