The morning of 8 May 1953 found the Independence-class light carrier Bataan (CVL-29) on station in the Yellow Sea, preparing to go into action. All along the wooden flight deck of the diminutive carrier, rows of Marine Corps F4U Corsair aircraft from Marine Attack Squadron 312 (VMA-312), the Checkerboards, started their engines. One by one, the distinctive gull-winged Marine aircraft roared into the morning skies to provide crucial close-air support to their embattled brethren on the ground in Korea.1

Providing close-air support was an unglamorous task and well beyond the mission set for a ship that nominally had been converted into a specialist antisubmarine warfare (ASW) carrier. Nevertheless, the Bataan and her Marine aviators demonstrated the flexibility, agility, and lethality of the Navy–Marine Corps partnership over the course of three deployments off the coast of Korea between 1951 and 1953. In those three years, the Bataan and the pilots of VMA-312 added seven battle stars to the six the carrier had earned during World War II, an enviable record even for one of the Navy’s far larger fleet carriers.2 It was a remarkable performance for a ship whose size and capabilities as a carrier were considered barely adequate by the Navy and that never would have existed had it not been for wartime exigencies and presidential intervention.

A Preference for Big Decks

To understand why the Bataan and the rest of the Independence class were an aberration for the Navy, it is necessary to examine the interwar years that led to the Navy’s preference for large carriers. At the end of World War I, aircraft carriers were a new and unproven weapon system, but one that showed great promise. The Navy heavily invested in the development of the hardware, techniques, and procedures needed to employ carriers at both the tactical and operational levels of war. This included at-sea exercises as well as extensive war-gaming at the U.S. Naval War College.3 The most stressing problem the Naval War College investigated was a conflict in the western Pacific against Japan. Such a war presented severe operational and logistical challenges to the U.S. fleet because of the distances involved and the lack of developed base infrastructure in the western Pacific. These war games pointed to both the importance and the vulnerability of aircraft carriers and their air wings.

The Naval War College’s games indicated that an advancing fleet would rely heavily on its carrier aircraft for scouting, protection, and attack, as it would be operating far beyond the range of friendly shore-based aircraft. Attrition was a significant concern; protracted operations inevitably would result in the loss of planes and pilots, whether from combat or accidents. Thus, the Navy concluded that carriers required air wings large enough to absorb some wastage and still remain combat-effective.4 Efficient operation of a large air wing, in turn, drove the need for a large carrier. Attempts to design and build a smaller carrier that could still operate a large air wing resulted in the Wasp (CV-7) and Ranger (CV-4), neither of which proved to be entirely satisfactory in the eyes of Navy leaders.5

During the interwar years, the Navy also executed design studies for carrier conversions from merchant ships and other types of warships, but these concepts were rejected over concerns that a lack of stability and the reduced size of the air wings that could be operated from them would render such conversions combat-ineffective. It was in the Yorktown class that the Navy found a suitable combination of size, mobility, and aircraft capacity, and it was these bigger, heavier flattops that would serve as the template for the wartime Essex-class fleet carriers.6 Thus, by 1940, theoretical war-gaming and practical experience at sea had led the Navy to develop a strong preference for large carriers over smaller ones, even if fewer of the larger carriers could be fielded.

The President Intervenes

The Navy started down the path to wartime mobilization more than a year before the attack on Pearl Harbor. Prompted by Japanese aggression in China and the German conquest of Europe, the United States began a massive naval expansion program in 1940 that was designed to prepare for a war that seemed to be just over the horizon. The ships ordered under the Two-Ocean Navy Act of 1940 included significant numbers of new fleet carriers, but the pace of construction for such large and complex vessels was limited by available shipyard capacity, which had to be shared with battleship construction. This prompted a search for a way to get new carriers into service as fast as possible.

In October 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who had maintained a keen interest in naval affairs since his years as an Assistant Secretary of the Navy during World War I, proposed that the Navy take a fresh look at carrier conversions. In a letter to Admiral Harold R. Stark, Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), Roosevelt expressed great interest in converting merchant ships into carriers for secondary duties such as convoy escort, antisubmarine warfare, aircraft transport, and air support of landing beaches—all jobs the Navy would consider inappropriate for full-size carriers under its nascent carrier doctrine.7 The Bureau of Ships (BuShips), keeping in mind the results of its interwar design studies, was unenthusiastic about the concept.

However, Roosevelt’s view was that an inferior carrier now was better than a superior carrier later, and, as a result of his direct guidance, the Navy initiated a project to convert the merchant ship Mormacmail into an aircraft carrier. The resulting ship was commissioned the USS Long Island (AVG-1) in June 1941. Perhaps reflecting the Navy’s initial uncertainty regarding the military utility of the ship, the Long Island went through three different type designations in short order, including aircraft tender, general purpose (AVG), then auxiliary aircraft carrier (ACV), and, finally, escort carrier (CVE). Despite the Navy’s misgivings, the CVE concept proved successful, and by the time the war ended in 1945, the United States would commission 122 CVEs.8 Small, slow, and sporting modest air wings, CVEs excelled in the secondary duties for which they had been intended. As useful as the CVEs were, however, their merchant-vessel origin made them too slow to keep pace and therefore operate effectively with the fleet carriers. For that, a fast warship would be needed as the basis of conversion.

The Light Carrier Is Born

The leading candidates for fast carrier conversions were the new Cleveland-class light cruisers then under construction; these ships were large enough and fast enough to keep pace with fleet carriers, and they could be finished in time and in sufficient numbers to provide a substantial boost to the carrier force. The converted carriers would be much smaller than the Essex class and were projected to operate less than half the number of aircraft, with far less spares, ammunition, and fuel. As with the CVE conversions, BuShips was not in favor of pursuing cruiser-based carrier conversions. In addition to the old worries about the fighting qualities of such conversions, there was new concern about interrupting the construction pipeline for the Cleveland class. Consequently, the General Board of the Navy formally decided against proceeding with the conversions on 13 October 1941, and for a time it looked as if the cruiser conversion project would end before it had really begun.9

Once again the President stepped in, and on 25 October 1941, directed the CNO to launch a new round of studies on converting cruisers into aircraft carriers.10 Roosevelt’s attention on the matter, along with the sudden urgency in the construction of warships of all types in the wake of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, provided sufficient pressure to cause the Navy to reverse its decision and green-light the cruiser conversion project. A total of nine cruisers were converted into aircraft carriers. They were named the Independence class, after the first ship to undergo conversion, and were type-designated as light carriers (CVLs). Admiral Ernest J. King, who had succeeded Admiral Stark as CNO, directed the conversion of the first three ships on 10 January 1942, with two more batches of three ships each following on 27 March 1942 and 2 June 1942.

Wartime Contributions

The resulting ships were far from the “gold-plated” carriers that BuShips and the General Board desired. In service, the Independence class exhibited many of the shortcomings the Navy feared they would—their aviation facilities were cramped and spartan, and their smaller flight decks were trickier to land on, as the small ships tended to pitch more in even a modest sea state. The net result was that the class was more prone to aviation mishaps.11 No matter; as President Roosevelt had hoped, the CVLs began to enter service in 1943 alongside the first of the Essex-class carriers, and by the end of the war, the Independence class would come to form more than a quarter of the Navy’s carrier striking power in the Pacific.12 While the CVLs did not quite live up to the Navy’s ideal for a carrier design, they had the virtue of being present and ready to fight as the United States went on the offensive against Japan.

All nine of the Independence-class light carriers were dedicated to operations in the Pacific. Operating alongside the fleet carriers, the CVLs saw action from the Marshall Islands to Okinawa and beyond. Initially, their air wings were split among fighters, dive bombers, and torpedo bombers, but by late 1943, they had been simplified to just fighters and torpedo bombers. This simplification was driven by a desire to maintain high numbers of fighters for air defense and by the difficulties encountered when handling SDB Dauntless dive bombers (which lacked folding wings) on the smaller flight decks and hangar bays of the light carriers.13 In a testament to their contributions to the war effort, the ships of the Independence class collectively earned 81 battle stars, three Presidential Unit Citations, and one Navy Unit Citation. Only one CVL, the USS Princeton (CVL-23), was lost during the war.

Postwar Service

In its immediate postwar analysis, the Navy concluded CVLs were too small to be truly effective. One report, while granting that the converted carriers “inflicted more damage on the enemy than they would have inflicted, probably, had they been built as cruisers,” went on to note a litany of limitations and constraints, including a small air wing, poor defenses, and cramped accommodations for the crew.14 The reasoning that drove the Navy’s prewar preference for large carriers was still valid, and in fact was only reinforced by the introduction of larger and heavier aircraft types that were increasingly unsuitable for operation from small carriers. Consequently, the Navy decided against the construction or conversion of additional CVLs.

However, the eight surviving CVLs still had some military value, and several saw service in a variety of roles during the Cold War, with the Bataan even serving as a platform for Marine close-air support in Korea.15 This reprieve was to be short-lived, however; all the CVLs were retired again by the mid-1950s, and, by 1970, all but the USS Cabot (CVL-28) were stricken from the register and sold for scrap. The Cabot received a stay of execution when she was transferred to Spain in 1967. She was retired for the final time in 1989 and returned to the United States for use as a museum ship. However, those plans failed to come to fruition, and, sadly, she met the scrapper’s torch in 2000 after having languished in obscurity at a pier in New Orleans for a decade.

Big Deck Amphibs: Spiritual Successors to the CVL?

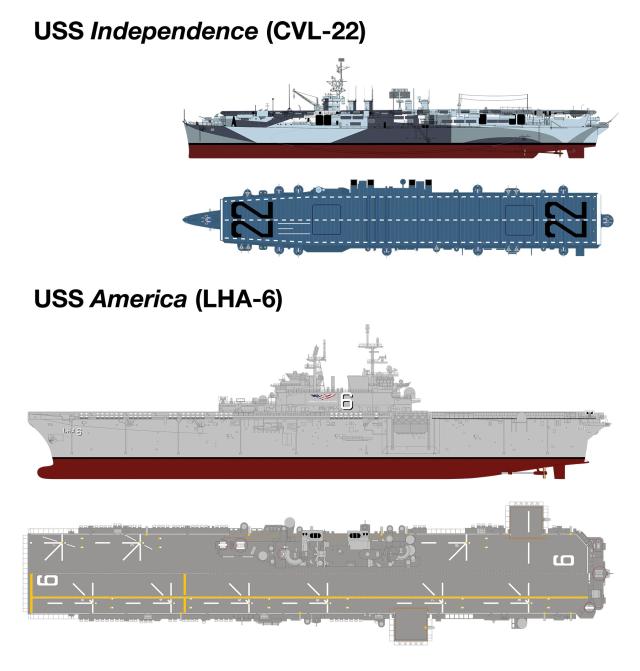

On 20 September 1997, more than four decades after the Bataan CVL launched her final combat sorties over Korea, the second Bataan (LHD-5) was commissioned in Pascagoula, Mississippi. A Wasp-class amphibious assault ship (LHD/LHA), the new Bataan, her seven sisters, and her cousins of the America class are colloquially referred to as “big deck amphibs.” While they are not classified as aircraft carriers, they certainly look the part with their large, full-length flight decks. In fact, the Wasp and America classes rival the World War II Essex-class fleet carriers in size, once again demonstrating the Navy’s institutional preference for large aviation platforms. However, despite their large flight decks, cavernous vehicle storage areas, generous troop accommodations, and, for the Wasp class, their well decks, these ships remain fully rooted in the amphibious doctrine of the Marine Corps.16

As the United States confronts the return to great power competition at sea, there is a growing discussion on alternative ways to employ the LHA/LHD force in some of the roles that were once filled by CVLs. Some of this consideration is being fueled by a growing recognition that the Marine Corps’ amphibious doctrine is in need of an in-depth update. In his 2019 Commandant’s Planning Guidance, General David H. Berger lays out a roadmap that steers the Marine Corps toward more flexible deployments less dependent on the historical force-level requirements for amphibious ready groups that in the past have limited the employment of the LHA/LHD force.17

Also fueling the discussion on alternative uses for the LHAs and LHDs is the arrival of the F-35B short-takeoff/vertical-landing variant of the joint strike fighter in increasing numbers. The F-35B Lightning II provides an LHA/LHD with aircraft that can match the performance of those employed from CVNs. But, even with the F-35B, an LHA/LHD is no match for the sustained combat power a CVN can deliver, just as World War II CVLs were a distant second to the capabilities of the full-size fleet carriers with which they operated. However, as was the case with the CVLs, the extra combat power that a “Lightning carrier” or two could bring to a high-end fight cannot be ignored. A glimpse of what a Lightning carrier might look like was provided by the USS America (LHA-6) in 2019, when she deployed in the western Pacific with a deckload of 13 F-35Bs.18

Flexibility and Innovation Are Key

The history of the Independence class is a classic case of nearly letting perfect be the enemy of good enough. It took presidential prodding to convince the Navy to accept a class of ships that was far from optimal in terms of design and performance but still capable of providing a significant and arguably indispensable boost to the combat power of the fleet. The CVLs formed a substantial portion of the Navy’s carrier force in the later stages of the Pacific war, and without them it is conceivable that many of the battles in 1944 and 1945 would have been far more closely fought and far bloodier.

Thus, the true legacy of the CVL is as a reminder that effectively responding to tactical, operational, and strategic challenges can require thinking outside the box. Today, the boundaries of the box would be defined by existing doctrines, peacetime deployment routines, and a reliance on the “gold-plated” standards for aviation platforms. If great power competition suddenly explodes into great power war, there may be little time to build additional ships to peacetime standards.

As with the CVLs during World War II, such conditions may force commanders to employ forces that otherwise would be considered suboptimal. In this climate of constrained resources and great power competition, current and future leaders of the Navy and Marine Corps will do well to bear the lessons of the humble Independence class in mind.

ν Lieutenant Commander Rucker graduated in 2005 from the U.S. Naval Academy with a bachelor’s degree in history. He recently completed a tour as the information systems officer on board the USS Bataan (LHD-5) and is currently assigned to Naval Computers and Telecommunications Area Master Station Atlantic in Norfolk, Virginia.

1. Naval History and Heritage Command, “Bataan I (CVL-29) 1943–1959,” Official Ship Histories.

2. Andrew Faltum, The Independence Light Aircraft Carriers (Mount Pleasant, SC: The Nautical & Aviation Publishing Company of America, 2002), 125.

3. Norman Friedman, Winning a Future War: War Gaming and Victory in the Pacific (Washington, DC: Naval History and Heritage Command), 75.

4. Friedman, Winning a Future War, 92.

5. Friedman, 97.

6. Friedman, 98.

7. Faltum, The Independence Light Aircraft Carriers, 8.

8. Norman Friedman, U.S. Aircraft Carriers, An Illustrated Design History (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1983), 148.

9. Faltum, The Independence Light Aircraft Carriers, 8.

10. Friedman, U.S. Aircraft Carriers, 181.

11. Friedman, 191.

12. Friedman.

13. Faltum, The Independence Light Aircraft Carriers, 16.

14. Faltum, 115.

15. Naval History and Heritage Command, “Bataan I (CVL-29) 1943–1959.”

16. U.S. Navy, “U.S. Navy Fact File.”

17. GEN David H. Berger, USMC, Commandant’s Planning Guidance (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, 2019).

18. Megan Eckstein, “Marines Test Lighting Carrier Concept, Control 13 F-35Bs from Multiple Amphibs,” USNI News, 23 October 2019.