In the early morning hours of a temperate January day, a contingent of 1,723 U.S. Marines defended an expeditionary advanced base on a small tropical island from an impending enemy amphibious assault. The Marines reacted quickly, having used airborne reconnaissance in the preceding days to build situational awareness of the enemy’s disposition.1 As the sun rose, the enemy was thrown back into the sea, and the base continued to provide support to the fleet. Thanks to investments in both time and money to innovate their force design, force structure, posture, and capabilities to support the advanced base mission, the Marines were able to successfully defend the island.

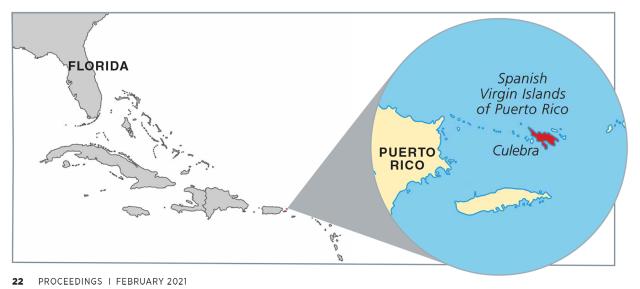

This is not a depiction of the Marine force of the future as outlined in the Commandant’s Force Design 2030, but an experiment conducted on Culebra Island off Puerto Rico more than a century ago—the culmination of much thought, debate, and conclusions about the concept of the advanced base force.2 This historical example has increased relevance today, as Commandant of the Marine Corps General David H. Berger has challenged the service to make sweeping changes not unlike those made by the Corps at the turn of the 20th century. It also is an example of how leadership can foster innovation and change to meet emerging threats.

The Need for an Advanced Base Force

At the turn of the 20th century, the U.S. Navy, influenced by the writings of Alfred Thayer Mahan, began to shift its focus toward maintaining a permanent peacetime force capable of projecting power far beyond U.S. shores. The need for a large fleet was compounded by the new U.S. territories in the Pacific and Caribbean, spoils of the Spanish-American War. Success in any future naval campaign would require the fleet to seize and hold strategically important advanced bases to support the logistical demands of a large, coal-burning fleet.3

The Marine Corps stood as the leading candidate to execute advanced base operations (ABO), for several reasons. First, the Department of the Navy wanted all matters of the naval realm—including advanced basing—kept within its purview, and away from its Army rival.4 Second, the Marine Corps displayed an aptitude for securing advanced bases during the Spanish-American War, when it deployed a battalion afloat to secure Guantanamo Bay as a coaling station for blockading ships. Last, with advances in technology increasing the range of naval engagements, the Corps’ role in providing security and sharpshooters for ship-to-ship combat was losing relevance. Many high-ranking Navy officers viewed the Marine Corps’ shipboard presence as wasted manpower and wanted to shift the service to this new mission. The Corps, however, was reluctant to address an advanced base role, fearing that removing Marines from ships would result in its disbandment.5 It was not the first or the last time a service would cling to an existing concept in lieu of innovating to meet new realities.

Despite these fears, on 11 November 1900, Commandant Brigadier General Charles Heywood accepted the ABO mission outlined by the Secretary of the Navy’s General Board. The Corps’ first step was to establish an advanced base school in Newport, Rhode Island, followed quickly by two ABO experiments in Annapolis, Maryland, and Culebra, Puerto Rico, to test the concept.6 The latter was particularly significant because of the extensive foundation in naval integration it established.

A Successful Exercise in Naval Integration

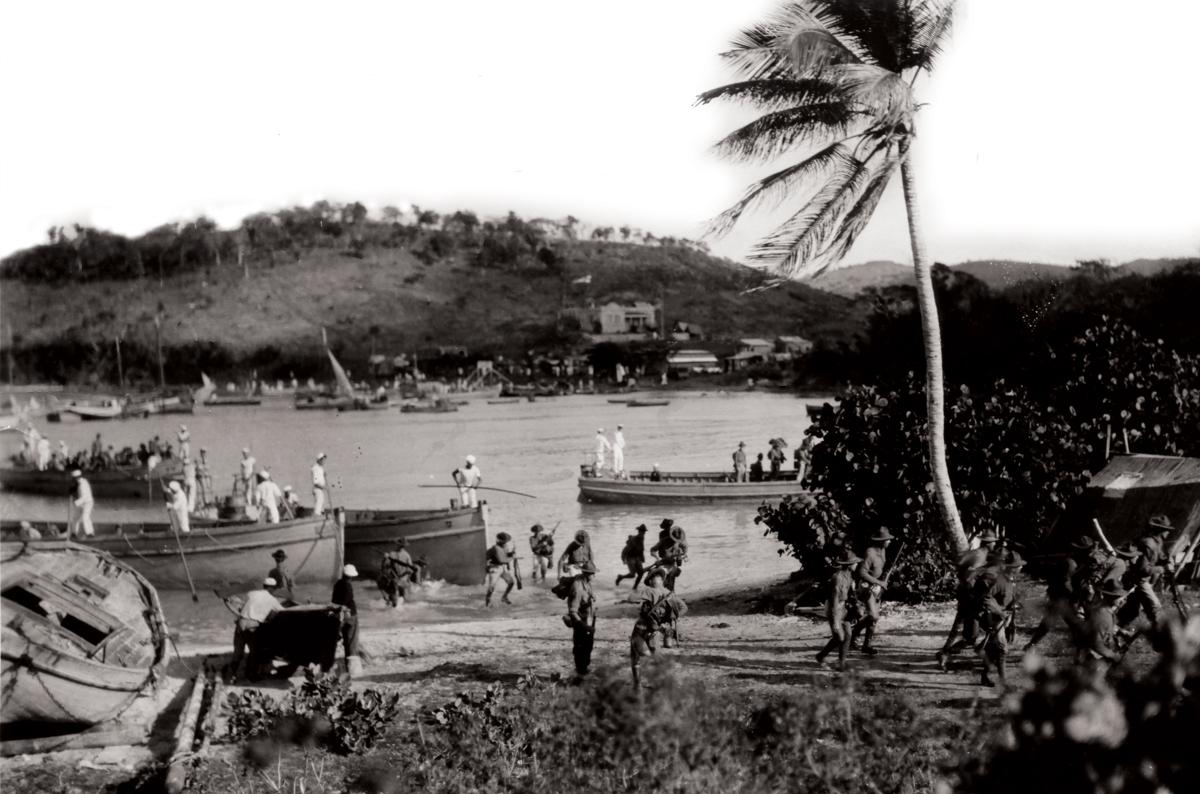

In 1902, two years after the Marine Corps accepted the ABO mission, Colonel Percival C. Pope led the largest Marine advanced base force since the Spanish-American War.7 Colonel Pope came ashore on Culebra with two battalions of Marines and immediately commenced final preparations for the concept’s first major test.

The force quickly ran into some unexpected problems. Most prominently, the Marines found most of their supplies had been loaded first on the transport ships, which now required them to unload all the ships’ supplies before they could execute their mission. In a letter to Commandant Heywood, Colonel Pope described this arduous process and stressed the importance of better coordination with the Navy during the initial loading of ships. In addition, they discovered a shortage of equipment needed to establish an advanced naval base, emplace coastal defense guns, and build fighting positions on the rugged island.8 Clearly, more thought was needed as to the required capabilities of an advanced base force.

Despite these setbacks, the maneuvers at Culebra were widely regarded as a major success of naval integration. In a note to Commandant Heywood, Rear Admiral Joseph Coghlan (the senior Navy commander at Culebra) wrote that the relative “high state of efficiency and the promptness displayed by the regiment were due to the hearty cooperation of the whole force working harmoniously to carry out the plans of the Department.”9

The amiable climate achieved between senior Navy and Marine Corps leaders likely eased any concerns the Marines might have had about self-preservation and the validity of their newly assigned mission. The exercise did, however, leave unanswered questions regarding how the naval force would leverage force design and force structure for an advanced base force. Nevertheless, the maneuvers at Culebra created a baseline for problem framing, academic study, and further execution.

Framing the Problem, Building the Solution

After the success at Culebra, the Marine Corps’ development of ABO was briefly eclipsed by other realities, such as the deteriorating situation in Mexico and a stress on manpower caused by various Caribbean missions. While other attempts at ABO took place, none were on the scale seen at Culebra in 1902.10

After prodding from the Navy’s General Board, the Marine Corps refocused its efforts on the ABO mission toward the end of the decade. The Bureau of Ordnance allotted $50,000 (about $1.4 million in 2020 dollars) for advanced base equipment and the Advanced Base School.11 Armed with backing from senior leaders, prior operational success at Culebra, and increased financial support, the Marine Corps was able to innovate from a position of institutional security.

The Marine Corps explored new ways of combining elements to create the advanced base force organization, such as merging two expeditionary advanced base regiments to form an expeditionary brigade. A fixed regiment would man coastal defense guns, field artillery, and mines, while a mobile regiment would maneuver against the enemy beyond the reach of the fixed regiment. An engineer company was included in the force design as a result of the lessons learned from building fortifications on Culebra. Finally, the advanced base force also would gain a searchlight and signal company.12

Realizing the strain on the force caused by the various Caribbean missions, naval leaders reexamined the Marine Corps total force structure to support the advanced base mission. They found the current structure did not allow for the creation of two expeditionary regiments. This triggered extra emphasis on the Marine Corps’ recruitment program to increase manpower. In addition, the Corps began to divest effort from other areas—such as the occupation of the Philippines and ship detachments—and consolidate expeditionary forces into one station in Philadelphia.13 These decisions allowed the Marine Corps the end strength to support the force design built for the advanced base mission.

In addition to force structure and design, the Advanced Base School focused on how the Marine Corps should define the advanced base posture. All future advanced bases would fall into two “bins”—temporary or permanent. Temporary advanced bases were to maintain a minimal presence, which could be built up and defended during times of war. The anticipated activities of these bases were defending against an attack by fire from the sea, preventing enemy maneuver through mining operations, and attacking an enemy outside friendly weapon engagement zones. Permanent advanced bases, such as Pearl Harbor, were characterized as being defended by extensive, permanent defenses with a large buildup of material and repair plants.14 These bins provided a framework for thinking strategically about advanced bases, which ultimately could ease tough manning and equipping decisions in the future.

Finally, the Department of the Navy began to look toward gathering equipment to give the Marine Corps new capabilities to execute the ABO mission. As more emphasis was placed on the mission, the Bureau of Ordnance provided $100,000 on top of the $50,000 initially promised.15 Even so, the Corps had to rely on outdated technology to gain new capabilities. One example was the Marine Corps’ acquisition of two 4.7-inch field guns from the Army to test as antiship weapons. In addition, the advanced base force was able to acquire an assortment of mines, one 5-inch, .51-caliber antiship gun, and several other permanent field guns. In a testament to joint integration, two Marine officers were sent to the Army School for Submarine Defenses at Fort Monroe, Virginia, to build their mine warfare competency.16 The last major addition to the advanced base force’s capabilities were two aircraft for reconnaissance as well as basic antiair defenses. 17

By the summer of 1913, the pieces were in place for the permanent advanced base regiment, and the service instituted an intensive training regimen. All that remained was an exercise to validate the force structure, force design, and new capabilities. Naval planners would turn to a familiar island in the Caribbean for this test.

The Culebra Maneuvers

With doctrine set and much theoretical and practical training complete, it was time to conduct an advanced base maneuver experiment. The General Board once again turned to Culebra for the test during the Naval Winter Maneuvers of 1913–14. U.S. planners felt Culebra would be the focal point of a potential war with Germany, dubbing it “the key to the Western Atlantic and the Caribbean.”18 Thus, the Culebra maneuver was not considered merely a practice run for potential advanced bases on islands in the Pacific, but rather an exercise whose success would bode well for the U.S. ability to maintain strategic control in its own backyard against a peer threat.

The advanced base force consisted of a brigade of Marines divided into fixed and mobile regiments, as outlined by the Advance Base School. Colonel George Barnett was placed in command of the brigade, Colonel Charles Long commanded the fixed regiment, and Lieutenant Colonel John Lejeune assumed command of the mobile regiment.19 The scenario built for the maneuver proposed that “Red Country,” which resembled Germany, would attempt to gain a foothold in the Caribbean. In response, the Marine Corps would embark its advanced base brigade and head to Culebra. The time spent integrating with the Navy enabled the Marines to conduct an efficient embarkation. Improvements included the appointment of a single embarkation officer and an emphasis on the “significantly complicated combat loading process” throughout embarkation.20 By 9 January 1914, both regiments had fully embarked, steamed south, and dropped anchor off the coast of Culebra. It took less than ten days to transition all men and equipment from both regiments ashore and finish the necessary emplacement of a temporary advanced base.

Colonel Barnett tasked the fixed regiment with establishing and defending the advanced base in the Great Harbor on the south side of Culebra. Adding an engineer company to the force design allowed the regiment to rapidly emplace its large coastal defense guns and construct the base. In addition, the fixed regiment rapidly deployed defensive mines in the harbor. Colonel Lejeune placed one of his mobile regiment’s battalions on the southeastern tip of Culebra to defend the harbor’s flank and the other in overwatch of the likely enemy landing beaches to the east and north.21

The Navy’s Atlantic Fleet, simulating the “Red Fleet,” began the joint exercise on the night of 18 January with simulated naval bombardments from its cruisers and destroyers. Responding in kind, Marines ashore began to simulate tracking and detonating mines underneath enemy ships. In addition, Marine aviators conducted reconnaissance and spotting flights during the day to locate the enemy. Coastal defense guns were fired with such enthusiasm that Colonel Barnett had to order batteries to “simulate fire by firing one blank charge as the first round” to conserve propellant for the planned post-exercise target practice.22

The climax of the exercise came in the dark on the 21st, when the Red Fleet attempted a landing on the western edge of Culebra in the early morning hours. The mobile regiment quickly responded, massing simulated “heavy rifle, machine-gun, and artillery fire on the approaching boatloads of sailors and marines.” Shortly after 0700, the umpires judging the exercise ordered a cease fire, ruling the island of Culebra “impregnable,” validating the ABO concept in execution.23

Past is Prologue

With fundamental changes throughout the force to meet emerging threats, it is now more important than ever to study how past leaders fostered innovation and institutional change. Five interwoven lessons, drawn from the Culebra exercises, should be applied as U.S. leaders guide the Marine Corps through another era of change.

- The naval service must attack change methodically and establish a framework on which to build. While the naval leaders of the day never explicitly spelled out the design levers of force design, force structure, force posture, joint/naval integration, and new capabilities, they did frame their thinking around those levers. The current institution already is on the right track, having built a framework of thought through the design levers outlined in the Commandant’s Force Design 2030.

- Leaders at all levels must lead innovation in the different design levers from a position of security. The General Board fostered an unthreatening environment in which bold innovation and ideas could be advanced. The Marine Corps was quickly able to divest missions to meet a new reality. Staunch adherence to this principle is important for a force to rapidly flex to meet any peer threat, whether against Germany in 1902 or China in 2021.

- Innovative ideas must move rapidly up and down the chain of command. Perhaps the best example was Colonel Pope’s direct communication with the Commandant about the merits of combat loading and strong naval integration. Many of these ideas were drawn out through wargaming and execution and implemented quickly by the force; today’s leaders must emphasize both tools.

- The naval services must devote time and money for innovation to succeed. It is easy to strangle innovation in the crib if the necessary resources are not available. New ideas were thoroughly wargamed, trained to, and tested in execution. Large sums of money and the Winter Maneuvers of 1913–14, a typically Navy-centric exercise, were dedicated to further a Marine Corps–centric mission.

- Sister services are important during the innovation process. The Navy was always present during ABO development, and Marine Corps leaders realized early that they would need the full support of the Navy to succeed. Cross-service coordination is hard, and future missions will require more integration than ever. It is a capability that must be practiced.

For ABO in the early 20th century, these lessons worked in concert, resulting in a more capable force ready to fight the next war. The ABO concept was further refined and became a key contributor to War Plan Orange, the island-hopping campaign of World War II, and the future identity of the Marine Corps.

Force Design 2030 challenges the Marine Corps to initiate an age of innovation and change to maintain naval supremacy against emerging peer adversaries. The leadership challenge of guiding change and nurturing innovation is not new. Leaders must provide a dedicated environment where assumptions can be safely challenged, ideas can rapidly move up and down the chain of command, and joint integration is at the forefront of decision-making. The force is ready to innovate and change to meet new threats. We have done it before, and we can do it again.

1. Graham A. Cosmas and Jack Shulimson, “The Culebra Maneuver and the Formation of the U.S. Marine Corps’ Advance Base Force, 1913–1914,” in Assault from the Sea, Merrill L. Bartlett, ed. (Annapolis, MD: U.S. Naval Institute Press, 1983), 129.

2. GEN David H. Berger, USMC, Force Design 2030 (Quantico, VA: U.S. Marine Corps, 2020).

3. Cosmas and Shulimson, “The Culebra Maneuver,” 121.

4. Kenneth J. Clifford, Progress and Purpose: A Developmental History of the United States Marine Corps, 1900–1970, Marine Corps History and Museums Division (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1973), 10.

5. Cosmas and Shulimson, “The Culebra Maneuver,” 123.

6. Leo J. Daugherty, Pioneers of Amphibious Warfare, 1898–1945: Profiles of Fourteen American Military Strategists (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2009), 72.

7. Clifford, Progress and Purpose, 8.

8. Daugherty, Pioneers of Amphibious Warfare, 46.

9. Daugherty, 47.

10. Clifford, Progress and Purpose, 11.

11. Cosmas and Shulimson, “The Culebra Maneuver,” 123.

12. Daugherty, Pioneers of Amphibious Warfare, 73.

13. Cosmas and Shulimson, “The Culebra Maneuver,” 124.

14. Daugherty, Pioneers of Amphibious Warfare, 72

15. Cosmas and Shulimson, “The Culebra Maneuver,” 126.

16. Clifford, Progress and Purpose, 13.

17. Daugherty, Pioneers of Amphibious Warfare, 73

18. Cosmas and Shulimson, “The Culebra Maneuver,” 127.

19. Clifford, Progress and Purpose, 18.

20. Cosmas and Shulimson, “The Culebra Maneuver,” 127.

21. Cosmas and Shulimson, 128.

22. Cosmas and Shulimson, 129.

23. Cosmas and Shulimson, 129.