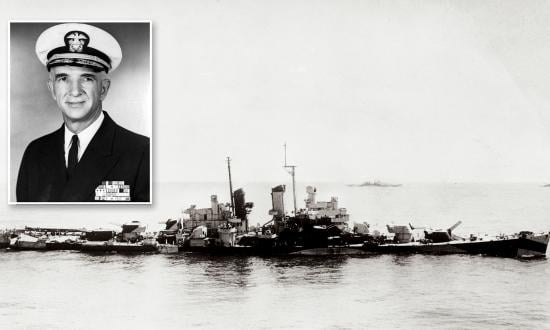

Vice Admiral Herbert D. Riley’s headstone at the U.S. Naval Academy cemetery reads “Ninth-generation Marylander.” A 1927 Academy graduate, he would rise to become director of the Joint Staff before his retirement in 1964.

In 1930, with his aviator’s wings newly pinned, he reported for scout plane duty on the cruisers USS Cincinnati (CL-6) and Richmond (CL-9). The latter was operating off Honduras, helping safeguard United Fruit Company interests during local uprisings. The ship was calming matters by showing the flag in local ports, coming in from deep water and steering up tortuous channels with underwater reefs and pinnacles. Having no reliable charts or depth-finding gear, the skipper would launch his scout planes, with pilot and radio operator instructed to tap-key safe-channel course changes from aloft.

Riley recalled one approach in his oral history published by the Naval Institute:

I had my radio operator tell them to take two more course changes, one to evade the pinnacle, and one to put them on a course clearing all obstacles.

The ship did not receive the message, secured communications, and continued toward disaster.

I made six low passes over the bridge and headed in the direction I wanted them to go; they simply ignored me. Finally, I decided there was only one way to do it, and that was to get well ahead of the ship and come down low on the water right at the bow, and at the last minute pull up over the bridge to indicate they should stop. We got the ship into Tela without hitting a reef.

In October 1944, Commander Riley took command of the escort carrier USS Makassar Strait (CVE-91) in the Pacific campaign. Coming out of the Kerama Islands, he launched a combat air patrol before dusk.

About then, we had a bogey reported on the screen. We were at general quarters, alert for kamikazes. We had a visual flight director: a fellow who controlled fighters visually—not by radar or radio —who picked up the bogey visually. It could not have been more than ten feet above the water.

We had just three planes in the air, and as the bogey came closer, one of them dove at it. His dive was no good. Next in line was a 19-year-old lieutenant junior grade by the name of Riggan. He started his dive and had to get almost on his back to keep his target in sight, and he had to pull out fast or he would hit the water.

But he was a smart pilot. After his next approach and first burst, he did a half roll to an ideal position for an approach shot from the rear. When Riggan’s second burst hit the Betty, it flamed straight down and blew as it came in.

Riggan was waved off on his first landing pass, then came in high on his second, floated, caught the last wire, and went into the barrier, damaging the prop. He was shaky when he answered the loud speaker’s call to “report to the captain on the bridge,” sure he was going to get chewed out.

We laughed that off. I congratulated him, and recommended him for a Distinguished Flying Cross for saving his ship from serious damage or loss, and he got it.

When Riley brought the carrier into Guam for work, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz invited him to dinner, followed the next evening by a dinner with Rear Admiral E. L. Gunter, whose first question was “Hey, where are your eagles?” The word had not reached Riley; he had been promoted to captain.

He was told to go to the dispensary for his physical.

When I got to the little Quonset hut the next morning, the medical officer said, “Here, sign this, sign this,” and then held out his hand and said. “Congratulations.” I asked about the examination. He replied, “Anybody who has been through what you’ve been through in the last few months doesn’t need a physical examination.” That was my promotion to captain.