As a new ensign on board the USS Merrill (DD-976) in 1979, I met a man who came on board for a family day cruise out of San Diego. He was old, barrel chested, and obviously enjoying being back at sea. We talked, and he told me he had been a boatswain’s mate in the Navy. What ship? I asked. The heavy cruiser Houston, he said. I was dumbstruck. At the time, I was reading about the Battle of the Java Sea and particularly about the Houston’s damage. I mentioned the loss of the Number 3 8-inch/55 gun turret. He nodded, telling me it was bad. He was one of the men who removed the remains of his shipmates from that turret. He then proceeded to tell me his story.

What did he focus on? The captain. Going into that last battle at Sunda Strait on 1 March 1942, Captain Albert Rooks told the crew they were in for it, and the ship would likely not survive the night. The skipper talked about what an honor it was to serve with such men, and said he hoped the best for each and every one. Then he announced that the ice cream bar would be open to all hands at no cost. This is what this gentleman remembered. He didn’t complain about the odds, or the danger, or the lost buddies. He focused on a great skipper and ice cream. He served out the rest of the war in the horrors of a Japanese prisoner of war camp. Sadly, I never learned his name.

In February 1942 the situation in the Far East was grim. Japan’s Pacific offensive was unfolding with relentless force. The United States’ small and battered Asiatic Fleet was reeling, having been chased out of the Philippines and now joining a polyglot collection of allied forces—the ABDA Command—in an attempt to stem the Japanese tide. History tells us they failed, and most died in the process. Yet they—American, British, Dutch, Australian, all of them—fought to the end.

This is not hyperbole or drama. It is fact. So, the question is, what made these sailors from various countries, as one, set aside their futures and their lives for a mission that, even to them at the time, clearly appeared headed for failure?

The Photograph

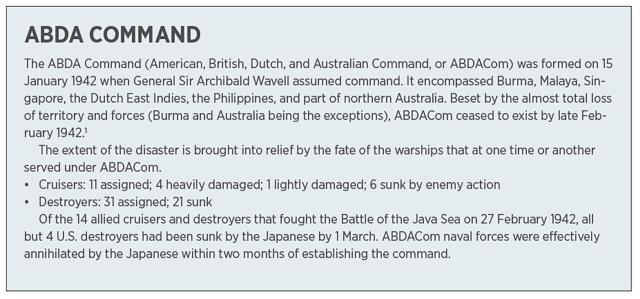

To explore this question, consider the photograph of the Houston (CA-30) as seen from the bridge of the old light cruiser USS Marblehead (CL-12). It tells a story, indeed, many stories. At first glance, it is unremarkable—one ship enters port, passing by another already tied up. But within a month, most of the men in the photo would be dead; the rest would be prisoners of war. This adds a gritty context and poignancy, a sense of tragedy, to the image. Maybe it is the normality, the sense of the everyday, juxtaposed with the reality behind it that makes the image so powerful.

The Houston and Marblehead had been bombed and damaged north of Java on 4 February. Both needed extensive repairs and withdrew to Tjilitjap on the south-central coast of Java, the only sanctuary left beyond Japanese aircraft. In the image, the Marblehead is passing the Houston early on the morning of 6 February. The Houston had pulled in the day before—it took the Marblehead that much longer to arrive because her rudder had been disabled in the attack and she had to steer by engines alone.

The Houston’s Number 3 8-inch turret is visible in the center of the image, trained to port. The 4 February attack knocked it out and took the lives of 48 men, mostly the crew of the turret and ammunition-handling rooms below. Note the shadows of the burnt-out life rafts on the turret top. Her flag is at half-mast while the burial party is ashore laying the dead crew members to rest. Houston sailors crowd the deck to watch the damaged Marblehead pull in. Walter Winslow, an officer on board the Houston at the time, reported that they stood to cheer the light cruiser’s crew, a cheer that was reciprocated by the exhausted Marblehead sailors.

Note the Houston’s weathered sides. They offer a clear indication of the relentless operational tempo being demanded of these ships since early December 1941. Constantly underway, often in combat, normally in a state of heightened combat readiness, far from maintenance facilities or any logistic support, with no flow of replacement parts, scant access to ammunition—frequently defective at that—and fuel scarce, the Houston and the other ships of the Asiatic Fleet and ABDA Command were barely hanging on.

What were those sailors thinking? Were they looking for ways to escape, to retreat to fight another day? Were they resentful of the conditions under which they were operating, of the fact that no reinforcements were coming, of the dawning reality that theirs was a forlorn hope that would meet a terrible end? Not so much. As best we can know from survivors’ stories, these guys—along with their comrades on the other ships—were focused on the mission and on taking it to the enemy. They were proud, determined, and aggressive, wanting nothing more than to dish it out to the enemy.

Walter Winslow conveys the condition and spirit of the crew:

Morale remained high, but the physical condition of the crew was poor. Most had not had a chance for anything one might call rest for more than four days because battle stations had been manned more than half that time, and freedom from surface contacts or air alerts had never exceeded four hours. This had caused meals to be irregular and inadequate. Nevertheless, the exhausted crew shrugged it off, for every man considered himself lucky to be alive, and was determined to give every last ounce of strength to bring the Houston through.

These were professionals, and they had to know they faced insurmountable odds. They knew they could not win. All they could do was buy time, impose costs, and make a statement. But they stayed, they fought, and they died.

As a result of the damage inflicted on 4 February, the Marblehead would be sent home for repairs. Except for a small commercial floating drydock, Tjilitjap lacked the necessary facilities. The Houston’s commanding officer had the same option, but with six still-functional 8-inch guns, Captain Rooks felt the situation warranted staying to fight. More important, perhaps, he likely saw the broader significance of the Houston and the other U.S. warships in the fight for Southeast Asia. His and his ship’s continued fight would send a message to the beleaguered allies in the region: The United States is with you and will not run.

While it was clear the Dutch East Indies could not be held, the brave Dutch forces deserved U.S. support. Australia, also threatened, could be defended, and it was important for Rooks and the remnants of the Asiatic Fleet to demonstrate U.S. willingness to stand and sacrifice for that goal.

Rook’s decision would cost him, many of his sailors, and his ship their lives. The rest of the Houston’s battles were fought with that aft 8-inch turret out of commission. She was sunk, along with the light cruiser HMAS Perth and the Dutch destroyer HNLMS Eversten in the Battle of Sunda Strait on 1 March 1942. Except for four U.S. destroyers, the entire ABDA Command force was lost.

This is the story this image tells. It depicts a single moment, but it is an oft repeated tale across naval history. In fact, the Houston’s saga was paralleled by many others in that period. The Royal Navy ships Prince of Wales, Repulse, Exeter, Jupiter and others, the remaining ships of the Royal Netherlands Navy, and the Australian cruiser Perth all have their stories to tell. Similarly, the other U.S. ships and squadrons of the ill-fated Asiatic Fleet—the destroyers that won the Battle of Balikpapan in late January 1942, the submarines that fought with defective torpedoes, the patrol planes of Patrol Wing 10—all fought bravely and with remarkable aggressiveness against truly insurmountable odds.

For the U.S. Navy, this aggressiveness was no accident—it had been consistently inculcated into the fleet for decades. And while the sacrifice of the Asiatic Fleet and its allies did little to stem the tide of Japan’s offensive, it signaled the commitment of the Americans to the fight and the eventual defeat of Japan.

Lessons for Today

The U.S. Navy in this interlude showed not only the willingness to fight and die for its mission and cause, but also the benefit of decades-long realistic preparation for the fight that had now come. Yes, the Asiatic Fleet lost against a determined and capable enemy, but it fought well even when at significant disadvantage, never flinching, always looking for ways to impose costs on the enemy.

Today’s Navy must look hard and with honesty at what is going to be required in a war with China in the western Pacific. The time may come again when America’s sailors must stand and be counted, when a mission might require the ultimate sacrifice, perhaps even when it is known that mission cannot succeed.

The men of the Houston and her sister ships hold lessons, if the Navy will avail itself of them: How to steel its sailors, stoke their courage, and give them the tools they will need for the test that is coming—not just material tools, but personal and moral tools. How to reorient to, and prepare for, warfighting. How to instill in sailors the toughness and discipline that will be required to prevail.

To get all that from a single photo is, admittedly, a bit over the top, but that is the story it tells. The Houston was a proud ship, well run, and with a good captain and professional crew. Yet, she was outgunned by even one of the several Japanese cruisers she faced in those days. She and those with her paid the price for slowing the Japanese advance, even as little as they did, but it was the mission.

A saying attributed to the Royal Navy holds: You have to go out, but you don’t have to come back. This captures the essence of the Allied situation in the western Pacific in early 1942, but it also is useful wisdom in these days of reemerging great power—and great naval—competition. Experiencing no sustained, high-intensity at-sea combat for more than 75 years, how can today’s Navy get its collective head wrapped around this truth?

1. CDR Walter. G. Winslow, USN (Ret.), The Ghost That Died at Sunda Strait (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1984), 97.

2. CDR Walter G. Winslow, USN (Ret.), The Fleet the Gods Forgot: The U.S. Asiatic Fleet in World War II (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1982), 211. Winslow survived the war in Japanese POW camps and went on to write stories about his shipmates, including “Courage Mounteth with Occasion,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 77, no. 8 (August 1951), and “The ‘Galloping Ghost,’” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 75, no. 2 (February 1949). Until the release of POWs at the end of the war, the Navy and the country knew only that the Houston had been sunk, but none of the details of her exploits.

3. The drydock was capable of handling only destroyer-sized vessels. Though the Marblehead was too large, they were able to get the bow in and dry to patch the underwater damage; the stern was too heavy, so the jammed rudder could not be repaired. U.S. Navy, “USS Marblehead (CL-12) Bomb Damage, Java Sea, 4 February 1942,” date unknown. See also Office of Naval Intelligence, Combat Narrative, “The Java Sea Campaign,” 13 March 1943.

4. This is largely conjecture on my part. Captain Rooks left no account of his thinking along these lines. However, as Asiatic Fleet flagship, Rooks must have had numerous conversations with the intelligent and perceptive Admiral Thomas Hart, the Fleet commander. Rooks was of a kind with previous flag captains such as J. O. Richardson and Chester Nimitz. It is hard to imagine he would not have thought about the broader purposes of his fight.

5. Naval History & Heritage Command, “Final Days of USS Houston, The Galloping Ghost of the Java Coast,” 29 February 2016. Captain Rooks died shortly after ordering the crew to abandon ship in the 1 March 1942 action in Sunda Strait. He was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

6. This is a major theme in Trent Hone’s Learning War: The Evolution of Fighting Doctrine in the U.S. Navy, 1898–1945 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2018).