On 14 March 2020, I transited through the mess decks on board the USS America (LHA-6) in the late evening. En route to my watch, I noticed a young lieutenant (j.g.) mentoring two junior sailors who recently had been accepted to the U.S. Naval Academy, providing insight on their upcoming adventure. This moment came on the eve of my fourth anniversary of joining the Navy—and prompted me to reflect on my experiences as both a mentor and a mentee, and on the value of mentorship throughout one’s career.

The young officer and junior sailors are at the beginning of what will be a life-changing experience. At this point in their careers, it would be beneficial to be open to the experiential guidance and constructive criticism of mentors.

Mentorship: Growth through Assistance

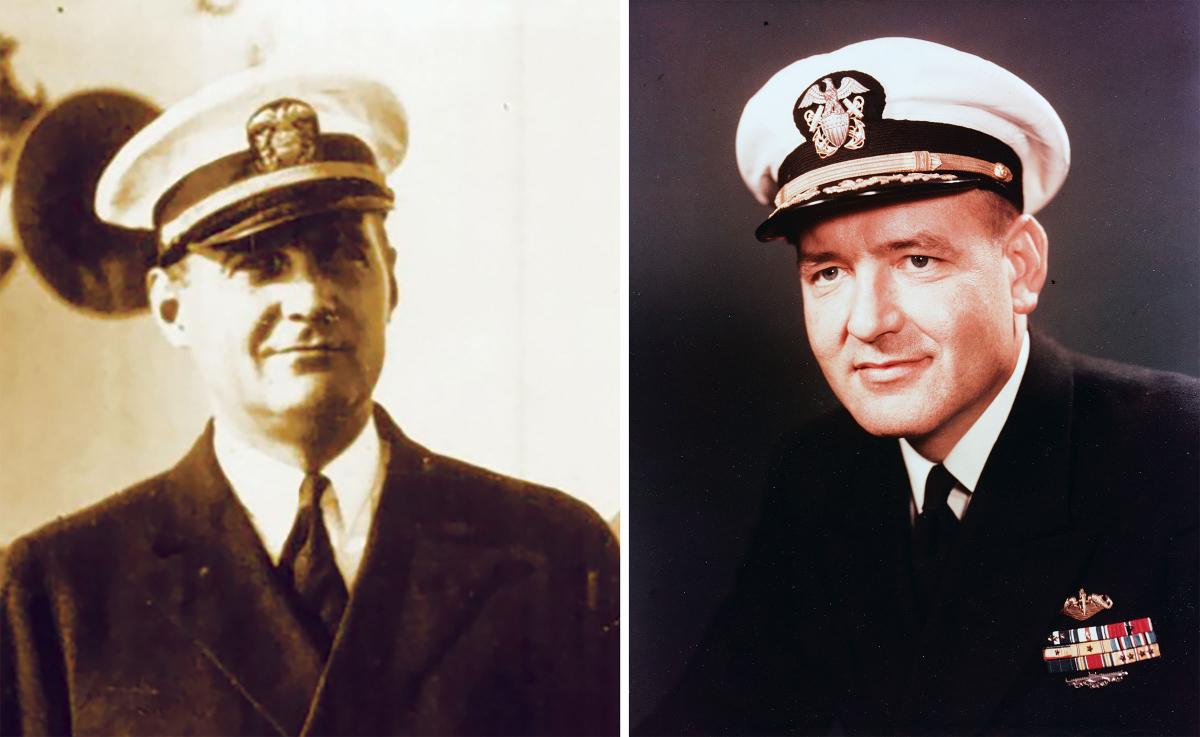

Today’s highly sophisticated, modern Navy cannot tolerate miscalculations and oversights; captain’s mast or early relief from a leadership position can summarily end a career. This is a drastic difference from more than a century ago, when Ensign Chester W. Nimitz was found guilty at a court-martial of running the USS Decatur (DD-5) aground in 1908, and Lieutenant Thomas C. Hart was relieved of his command of the USS Lawrence (DD-8) for insubordination. These two incidents would surely be handled much more harshly today, but these two officers went on to reach the rank of admiral during World War II.1

While it is certain that no career will be perfect, it is expected that overwhelmed and undertrained junior sailors be treated with respect and given realistic expectations from their leadership. This form of “tough love” must be advantageously planned and is crucial for junior sailors’ development as well as the welfare of the greater mission.

Captain Slade D. Cutter was relieved as commanding officer of the USS Seahorse (SS-304) following his fourth successful war patrol in the Pacific during World War II. Rear Admiral John H. “Babe” Brown released Captain Cutter for a month of leave and issued subsequent detaching orders. The Seahorse was to receive a new commanding officer. Cutter later reflected:

I learned after the war that Admiral Brown felt I was becoming too . . . reckless. . . . he [RADM Brown] had no intention of giving Seahorse back to me. . . . Had I gone on a fifth patrol as skipper, I might not have come back. Babe Brown was an insightful man.2

It was clear to Captain Cutter that even the highest ranked sailor can benefit from mentorship.

Cutter’s legacy would not be one of failure, but one of a skipper who had earned the trust of his sailors over the course of four highly successful and influential combat patrols in support of the Pacific campaign.3

Admiral Brown’s ability to recognize and employ the right leadership strategy at a favorable time during the mission provides a guide for today’s fleet.

Find a Mentor: “Babe” Brown

No two sailors are the same, and every member of today’s Navy has different needs—and responses—to guidance and constructive criticism. While each mentee requires different help, there is an outline of what to look for in a mentor.

Master Chief Petty Officer of the Navy Russell L. Smith outlined, in Laying the Keel, characteristics of the most exemplary ideals in sailorization: toughness, integrity, accountability and initiative.4 Admiral Brown embodied the ideals of toughness and integrity in his decision to remove such a successful skipper from his post.

In my own search for a mentor, I spent time considering several characteristics that would benefit my growth as a sailor, regardless of how difficult the process. I wanted someone who would push me to be better, someone in whom I could confide, and someone who would be honest with me if I strayed from the right track. My own inability to recognize what fights were worth fighting would be mitigated by the person I chose as my mentor.

I received advice from my peers and leaders to look outside my department to offer me a different perspective from those of my coworkers. My search led me to a chief aviation boatswains mate whom I barely knew, but who would end up being one of the greatest influences during my tour on board the America. Prior to transferring, he provided invaluable insight and advice to help me succeed. He often challenged me to look inward to identify my own flaws that had contributed to the issues at hand. A mentor who is supportive and evaluative can provide insight and productive reinforcement. Once I began working with my mentor, I was better able to accept the reality of the situation and develop suitable approaches to achieve my goals.

Be a Mentor: Fox Conner

World War II Generals George Marshall, Dwight D. Eisenhower, and George Patton share one thing in common: all were mentored by Major General Fox Conner during their careers. They collectively credit Conner’s insight for the courses they eventually would take as officers. General Patton attributed Conner with introducing him to the tank, and General Marshall received one-on-one mentorship from Conner early in his career.5

However, Fox Conner’s mentorship style and ability were best demonstrated through his interactions with Major Dwight D. Eisenhower. Conner studied nightly with Eisenhower, putting him through an analytic war strategy gauntlet that the eventual Supreme Allied Commander would refer to as “an education far beyond what any War College could provide.”

Conner taught three principles to his mentees:

1. Never fight unless you have to.

2. Never fight alone.

3. Never fight for long.

He personified the second principle through his mentorship, spending countless hours training future leaders and also sharing his counsel throughout his retirement. During the crucial planning for World War II Operations Torch and Overlord, Generals Marshall and Eisenhower dispatched classified couriers carrying maps and plans seeking Conner’s advice and guidance. In their correspondence—although they would come to outrank Conner—both men simply referred to him as “The General.”6

Fox Conner’s mentorship demonstrated humility, selflessness, and keen insight. He identified key attributes in his mentees and developed the whole person into a cunning leader. His forward thinking prepared the three generals for the war that would come after his service had ended.7 In my own case, my chief demonstrated these characteristics and emphasized their importance even after his time in the Navy was over. Along with the standards he upheld as a Navy chief, his own insight and selflessness were examples of how simply being a good person who works hard at their job can make all the difference.

The Navy has a constant need for stellar leadership during periods of rapid development in technology and fluctuating social dynamics. In A Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority, Version 2.0, former Chief of Naval Operations Admiral John C. Richardson expressed the need for a “naval force that produces outstanding leaders and teams . . . that learn and adapt . . . [to] maximize their potential and be ready for decisive combat operations.”8 Dedication, care, and mentorship by committed supervisors will produce a robust cadre of the future leaders outlined in Design. Admiral Brown and Major General Conner demonstrate the need for mentorship throughout a sailor’s career. Captain Cutter understood individual sacrifices must be made for the success and safety of mission and team. And, just as important, staying open to advice and guidance early—and late—in the course of a career is vital for the development of service members, young and old; mentors such as “Babe” Brown and Fox Conner are key to setting the stage for the next generation of the Navy.

1. CDR Joel I. Holwitt, USN, “‘Confidence in His Team,’” U.S. Naval Institute Naval History 33, no. 5 (October 2019).

2. Holwitt, “‘Confidence in His Team.’”

3. Holwitt.

4. MCPON Russell L. Smith, USN, Laying the Keel (Washington, DC: Department of the Navy, May 2019).

5. Edward Cox, Grey Eminence: Fox Conner and the Art of Mentorship (Stillwater, OK: New Forums Press, 2010), 79; and George C. Marshall, Memoirs of My Services in the World War 1917–1918 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1976), 120.

6. LCDR Jason Shell, USN, “Leading Outside Command,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 141, no. 12 (December 2015).

7. Shell, “Leading Outside Command.”

8. ADM John M. Richardson, USN, A Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority, Version 2.0 (December 2018), 16.