What “spark” or “trigger” will set the next war in motion? This question implies some peacetime crisis will escalate suddenly into armed strife that no one wants. There is no gainsaying that possibility—witness the brinksmanship during the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, which brought the United States and Soviet Union to the verge of global nuclear war despite misgivings among decisionmakers in Washington and Moscow. Something similar could befall the world in the coming months or years.

But national leaders also make conscious decisions to strike sparks or pull triggers. In fact, to switch metaphors, military history is replete with strategic leaders who saw a window of opportunity and resolved to act before it slammed shut. East Asia has seen its share of opportunism. Imperial Japan was the region’s rising power during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Japanese leaders pieced together a battle fleet with British help using imported boilers and other major components. That fleet took to the Yellow Sea and stunned naval experts by crushing the Qing Dynasty’s Beiyang (Northern) Fleet off the Korean west coast in 1895. Only in the past few decades has China’s navy made a comeback.

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) next cast eyes on tsarist Russia, which banded with fellow European powers to deprive Tokyo of the bulk of its gains from the Sino-Japanese War. IJN commanders glimpsed a fleeting opportunity. They studied the Russian Navy’s Far Eastern fleet in 1903. Careful scrutiny revealed that the IJN Combined Fleet overshadowed the Russian armada but would not for long. Russia’s European shipyards were building battleships. New-construction warships would soon make their way to the Pacific, combining their firepower with ships already on station. Japanese superiority would vanish—perhaps forever. So, the Imperial Japanese Navy acted. In February 1904 a torpedo-armed detachment of IJN destroyers lashed out at the Russian First Pacific Squadron at Port Arthur.

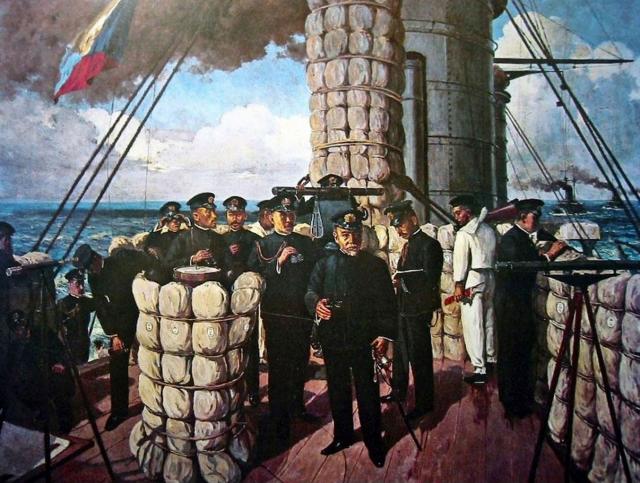

Admiral Togo Heihachiro on the bridge of the battleship Mikasa.

Japan went on to record a convincing if incomplete victory in the Russo-Japanese War, prevailing over its bulkier but overextended enemy. Preemptive logic animated Tokyo again in 1941. For decades, IJN strategy envisioned unleashing submarine and air attacks to debilitate the U.S. Pacific Fleet during its westward voyage to aid the Philippines following the outbreak of war. Then the IJN battle fleet would fall on its enfeebled archfoe somewhere in the Western Pacific. Early in 1941, however, the military leadership yielded to Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto’s entreaty to preemptively raid the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor.

fleet at Pearl Harbor in 1941 to take advantage of a closing window of opportunity. (photor courtesy

of Naval History and Heritage Command)

Yamamoto hoped to forestall U.S. intervention in the Western Pacific. The U.S. Congress had authorized a massive shipbuilding program in 1940, but it would take time for shipwrights to fit out the new fleet, and still more time for crews to steam it to the Pacific and ready themselves for battle. Here again Tokyo availed itself of a moment of opportunity. IJN carrier aviators took most of the prewar U.S. Pacific Fleet off the table—earning Japanese forces a respite to conquer most of maritime East and Southeast Asia. And so, they did.

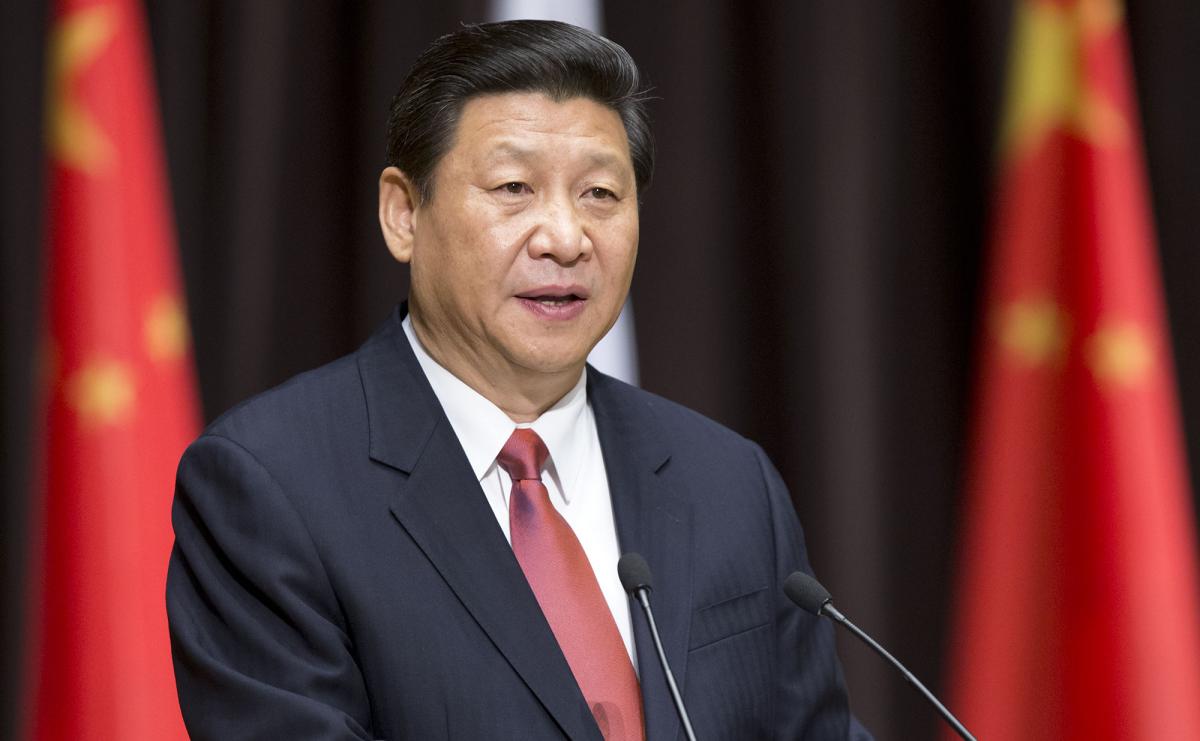

Now-or-never thinking, then, captivates makers of strategy. If the next antagonist is China, my guess is that senior Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leaders will likewise make a calculated decision to strike. Beijing would probably aim its aggression at Taiwan, but the blow could fall most anywhere around the Chinese periphery. The East China Sea, South China Sea, or Himalayas could become battlegrounds should Beijing opt for military action. CCP history supports such a forecast. Decisionmakers in Beijing have displayed a penchant for opportunism time and again. They single out an isolated and outmatched opponent. They wait until powerful outsiders who might intercede are distracted or occupied elsewhere. Then they pounce.

In 1974, for instance, Chinese naval and militia forces pummeled the South Vietnamese Navy in the course of wresting away some of the Paracel Islands. Saigon was teetering on the brink of defeat against North Vietnam, making its navy easy prey. Washington—consumed with Watergate and having mostly withdrawn from Indochina—had no desire to return. Opportunism prevailed, setting a pattern that governs Chinese maritime operations to this day in the South China Sea and elsewhere. During the 1990s, for instance, Beijing purloined Mischief Reef from the Philippines while Washington was preoccupied with Balkan wars. Engineers built infrastructure atop the reef, and today it constitutes part of China’s network of fortified outposts in the Spratly Islands.

This is classic window-of-opportunity thinking: isolate the adversary diplomatically and militarily, act swiftly and decisively, and stop. Strategic grandmaster Carl von Clausewitz endorsed it under certain circumstances. He went so far as to advise the weak to make war against the strong if they calculate that their chances are better today than they ever will be. Suppose, wrote Clausewitz, that “a minor state is in conflict with a much more powerful one and expects its position to grow weaker every year. If war is unavoidable, should it not make the most of its opportunities before its position gets still worse?” Yes, he says. It is in “the smaller party’s interest . . . to settle the quarrel before conditions deteriorate” further.

Much, then, depends on how Xi Jinping & Co. chart the military trendlines in maritime Asia. Two dangerous scenarios stand out. One, hubris—outrageous arrogance—appears baked into Communist China’s way of diplomacy and warfare. These are people indoctrinated to believe ‘History’ (with a capital H) is on their side. Ultimate triumph is inevitable. CCP magnates might believe their moment has come. They might see the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) as ascendant, the U.S. Navy and military in disarray, and U.S. alliances under strain. Such an estimate might convince the CCP’s Politburo Standing Committee they can act with impunity. And they might try it.

Or two, Beijing might embrace the Japanese and Clausewitzian brand of opportunism. If strategic overseers reckon the trendlines are turning against China and its PLA, they might conclude now is as good as the strategic conditions will get. For instance, they might see economics turning against them after China’s impressive thirty-year rise. They have cause. Demographics is a self-made catastrophe for Beijing after decades of forbidding families to have more than one child. In the coming years there will be fewer and fewer workers generating tax revenue to support more and more retirees. Military spending could lose out. The United States, Japan, and other trading partners are “decoupling” their supply chains from China, at least in part. China’s war potential might soon nose over into decline—taking with it the PLA’s ability to mass overwhelming firepower in the Taiwan Strait or elsewhere in China’s environs.

Chinese strategists, furthermore, might resist being seduced by hubris vis-à-vis the U.S. military and allied forces. For every bad-news story out of the U.S. Navy—fire on board the USS Bonhomme Richard (LHD-6), COVID-19 madness on board the USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN-71), the 2017 ship collisions, and so on—there is a good-news story. New ships, planes, and weapons are joining the inventory. The Navy and Marine Corps are exploring new ways to integrate their firepower. New leaders have vowed to correct the cultural woes that helped permit the embarrassments of recent years. If CCP leaders conclude that the U.S. Navy is on the rebound, they might see themselves as on a deadline: strike now or relinquish cherished interests for all time.

That is why the second alternative future is doubly replete with hazards. An increasingly brawny and confident China can act at its leisure; a China that feels beleaguered might act in haste for fear of seeing its window of opportunity closed—and painted shut forever.

Therefore, we must keep close tabs on how Beijing gauges the military balance—and stay on guard.