Naval Intelligence Essay Contest—First Prize

Cosponsored by the Naval Institute and Naval Intelligence Professionals

It is 2035 and a major crisis is brewing in the Pacific Ocean. The U.S. Navy’s Maritime Operations Center at Pacific Fleet headquarters is now the center of the world. A predictable scene follows. An intelligence officer stands in a crowded room—full of monitors and screens—and begins to brief the commander.

The briefer clicks through a few slides that the staff has labored all night to produce. The commander quickly interrupts with a question: “Lieutenant, where exactly is that embarkation port you just mentioned?” The briefer clicks back and forth among the slides; none show the location mentioned in the intelligence report. “I’ll have to get back to you on that, ma’am,” he replies; the walls are full of digital screens, but there are no paper maps.

Several slides later, the commander stops the brief on a slide with a range ring and asks, “How many of those missiles do they have in the inventory?” The briefer remembers seeing the answer in a report on his screen a year ago (or was it at the schoolhouse?)—he is sure he could find that report if he had 20 minutes at his desk: “I’ll have to get back to you on that, ma’am.” Three more times in the briefing he says he will go get the information the commander needs to support the critical decisions she is about to make.

Then the lights flicker. Monitors go off, and the slides disappear from the screen. The staff begins to discuss whether this is a maintenance problem or a cyber attack. The briefer remains at the front of the room. “Do you have anything else, lieutenant?” the commander asks. “No ma’am,” he replies, feeling useless without his slides.

The commander’s questions were good ones that should have been answered. This briefer’s experience is all too typical: Despite his dedication to the job and all the resources at his disposal, he did not bring knowledge to the scene of decision and empower his commander.

The naval intelligence officer’s overreliance on digital tools in this short scene is not improbable. Naval intelligence needs to strike a better balance between digital and analog tools to improve how intelligence professionals learn about the adversary, and sharpen how intel officers communicate those insights to decision makers.

The Illusion of Learning

The fusion of the five designators that make up the information warfare community has increased an intelligence professional’s required knowledge. Yet the community insists on training and certifying its professionals using ineffective learning techniques and an overreliance on digital tools. This leads to an erosion of knowledge quickly after earning one’s warfare pin. For a profession that claims to be committed to learning and communication, it neglects the body of science on how humans actually learn and communicate.

In 1885, German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus made important discoveries on how humans learn and retain information. He includes these in his seminal work on the “forgetting curve”—the loss of learned information. Ebbinghaus and others developed a method for memorizing important knowledge using structured review and repetition.1 However, many naval intelligence officers subscribe to the “pump-and-dump” method of learning and lose knowledge shortly after satisfying their qualification.

Today, most intelligence professionals learn primarily through passive techniques, by listening to instruction but with no collaborative back-and-forth with the teacher, no real intellectual engagement or linking of ideas.2 This is the core of a naval intelligence professional’s learning: long hours looking at slides while listening to an instructor rattle off bullet points. Meanwhile, young officers, in an effort to qualify for their warfare device, simply walk around with their personnel qualification standard (PQS) in hand, all too eager to sit and passively listen to an officer explain, line item by line item. Digital tools, often online networks, are used to quickly find answers to questions. This might answer the immediate question or fulfill a PQS signature, but it does not build a baseline of knowledge that is retained and can be called on years later. Digital tools can make it possible to quickly search and retrieve data, but they should not supplant foundational knowledge gained through active learning, including repetition and memorization.

Sophisticated analysis and critical thinking rest on foundational knowledge and patterns drilled to familiarity. The ability to recall this knowledge and recognize patterns intuitively atrophies with overreliance on digital tools. The link between active learning, memory, and navigation has been demonstrated in brain science studies on subjects ranging from laboratory animals to London cab drivers, and new research is raising the alarm about “spatial cognitive deskilling”—namely, a reduced ability to navigate and think critically about the surrounding environment because of excessive reliance on tools such as GPS and digital maps.3

In many cases, because analog tools require more cognitive effort on the part of the user, they make a better contribution to active learning. By synthesizing the information taught and forming new logical and spatial relationships in the brain, active learning produces an “active visual manipulation that generates new knowledge.”4 Active learning and memorization train the brain: exercising an officer’s mental muscle and preparing it for sophisticated critical thinking about higher-order problems.

Analog learning tools are like free weights: a simple, proven method for building (mental) muscle. Naval intelligence must preserve and extend the value of these tools. The growing role of artificial intelligence, machine learning, virtual reality, and new digital tools will not negate the need or diminish the rewards of analog tools. The following recommendations will improve the intelligence officer’s mind and prepare the community for an unpredictable future.

The Knowledge Professional’s Tool kit: Active Learning

There are many proven tools naval intelligence officers can use to improve this passive learning curve and embrace more active learning in training and on the job.

A first step toward active learning begins with encouraging handwritten note-taking in training classes, and should include greater use of hand annotation in routine analysis.5 Officers trying to master the enemy’s order of battle should make their own notecards and reference documents (cheat sheets). Receiving a gouge book is not the same as making it oneself: The process of drafting a reference sheet eventually obviates the need for it—by collating, condensing, and processing the data, the officers learn it for themselves.

Flashcards are a proven analog tool, but what should today’s naval intelligence officers be memorizing? In World War II, intelligence officers would drill aircraft silhouettes with slideshows, and playing cards with silhouettes were popular gimmicks for teaching aircraft recognition in military and civilian populations. The nation’s more recent wars have produced decks of playing cards depicting people, such as key figures of the Iraqi regime. But the foundational knowledge of operational intelligence for the type of conflicts and adversaries prioritized by the National Defense Strategy should emphasize the right geography and technology. A deck of playing cards (or handmade flashcards) for today’s challenges should include key bases, distances between locations, characteristics of key military platforms, and the ranges and capabilities of key missile systems. In addition, in the age of what Chinese strategists call “informatized warfare,” it is essential to know (without looking it up) which parts of the electromagnetic spectrum a system uses to sense, communicate, or attack.

Finally, officers should embrace analog methods of active visualization by making their own maps and diagrams when studying a problem. Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan himself found this technique useful: He describes using cardboard models to visually re-create past naval battles as he analyzed them for his early works on sea power.6 Similar examples of effective visualization for studying operational problems and developing new solutions are the early 20th-century gaming floors at the Naval War College and the Royal Navy’s Western Approaches Tactical Unit during the Battle of the Atlantic.7 As with handwritten notes and personalized study aids, forcing a person’s mind to visualize a dynamic situation through his or her own eyes enables active study of that problem.

The Knowledge Professional’s Tool kit: Communicating

The way naval intelligence officers perform their duties has changed little in recent years, despite advances in the civilian knowledge economy.8 The use of digital tools is stale and lackluster, but bringing new digital resources to the professional toolkit is only part of the solution. Many of the operations for which these tools are needed also can be done with analog tools that serve an intelligence professional in studying the adversary, and are essential to communicating that knowledge in a coherent way.

Paper beats pixels. Large-format displays are valuable tools to illustrate a point in the moment or to serve as an “information radiator” or “kanban board” that groups can use as they come and go and a situation unfolds.9 There are good reasons why classrooms have always been filled with chalkboards, whiteboards, and maps. But in recent years, large digital screens have taken over conference rooms and displaced analog methods for large displays. Electronic displays have many advantages in the types of media they can present, but they also can reduce the resolution of the information relayed to the viewer. Statistician Edward Tufte points out that a printed sheet of paper can contain far more data and graphics than a screen, arguing that an 11” x 17” sheet folded once to be a “four-pager” easily “shows the content-equivalent of 50 to 250 typical [PowerPoint] slides.”10

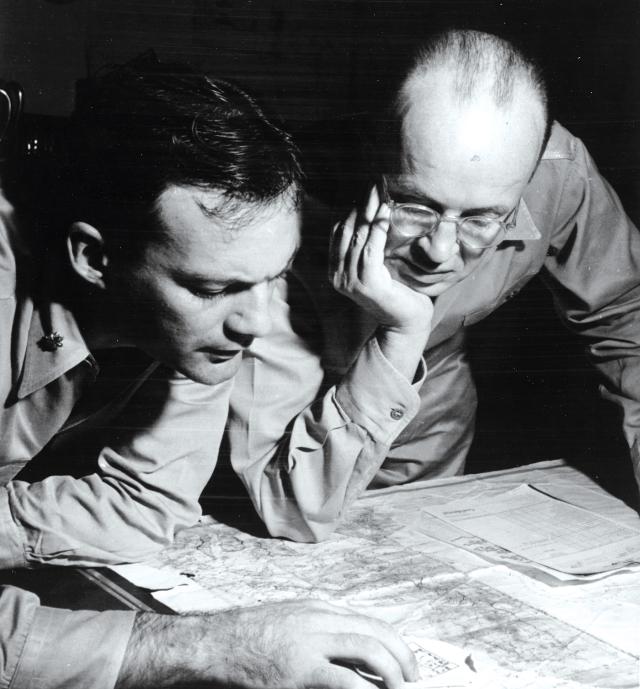

Google Earth and powerful geographic information systems are valuable research and analysis tools, but analog maps remain superior in many settings. Napoleon was known to lie down on a massive table to study detailed maps with his staff; President Abraham Lincoln kept a map folded in his pocket when he visited Grant in the field; and President Franklin D. Roosevelt would study wall charts with his staff and then draw on maps to illustrate a point.11

Large physical maps or charts can do many things that images on a screen cannot. First, they can display a geographic area in its entirety at a resolution and a relative size that most computers and screens cannot match. Second, when a map is placed on a table, it encourages collaborative learning—admirals and their staffs gather around, pointing, discussing, and annotating it. This creates an interactive discussion that no digital format can accomplish. And finally, they are aesthetically pleasing. A beautiful map with the right detail has a magical effect, inviting deeper study and tactile engagement.12

At their best, knowledge management efforts do not lock users into exclusively analog or digital formats—they strike a balance. Just as ubiquitous printers make digital words and images more permanent and portable, scanners and software allow users to digitize, share, and render searchable their analog holdings. Scanners and digitization software, however, are not deployed widely enough in the intelligence community. All-source intelligence officers would be more effective with fewer barriers to scanning foreign language publications and media, preparing them for databasing and computer-assisted translation with optical character recognition, and cross-referencing with other databases. The same tools also would aid officers in storing and sharing the notes, personalized references, and visual aids they generate in active learning.

Rock beats paper. Physical objects, such as scale models and sand tables, present a three-dimensional and tactile connection to a problem set. A briefer can manipulate the object to visualize its position and context in space and time. For example:

- Manipulating multiple models together allows a briefer to tell a compelling and dynamic story. For decades, aviators have used simple model aircraft on sticks to analyze and explain the subtle relationships of speed, angles, and distance in combat engagements. Intelligence professionals should use similar means to re-create close encounters and dangerous maneuvers in the South China Sea, using detailed models that faithfully depict the relative size, shape, and motion of the ships. Briefing with this technique would take Mahan’s method for analyzing positions and use it to communicate analytic conclusions.

- Terrain and building models, from crude sand tables in the field to works by professional model makers, are another proven analog technique used to prepare units for deployment, plan daring raids, and brief Presidents.13 Today’s intelligence professionals could communicate more effectively by breaking out of formulaic slideware and embracing visual aids with three dimensions. They could strike a balance of digital and analog by using inexpensive 3D digital printers to create physical models as dynamic briefing aids.

Embrace your inner artist. The suggestions above call for intelligence professionals not only to use more analog tools, but also to employ them creatively in ways that might seem outmoded or unpolished. The true test should be the effectiveness of the communication. It was not too long ago that drawing pictures by hand was a valued skill among military officers. A hand-drawn diagram may not look as “finished” as a PowerPoint slide, but it will be truer to the precise point the officer is trying to convey, can include more details and subtlety of line than PowerPoint will ever allow, and will prove field-expedient when everything else breaks.

Balance Digital Tools with Analog Ones

The emphasis on analog tools for the naval intelligence community is not nostalgia. War games are not “played” for fun. Making flashcards is not childish, drawing is not idle doodling, and arranging models is not playing with toys. If Mahan was willing to make his own models and FDR marked up maps by hand, perhaps these techniques can serve intelligence officers today—and in the future.

1. Jaap M. J. Murre and Joeri Dros, “Replication and Analysis of Ebbinghaus’ Forgetting Curve,” PLoS ONE 10, no. 7, e0120644, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0120644.

2. Brooke Hahn, “How People Learn Best: Active vs. Passive Learning,” The Learning Hub, 10 December 2018, learninghub.openlearning.com/2018/12/10/how-people-learn-best-active-vs-passive-learning/.

3. Eleanor A. Maguire, David G. Gadian, Ingrid S. Johnsrude, Catriona D. Good, John Ashburner, Richard S. J. Frackowiak, and Christopher D. Frith, “Navigation-Related Structural Change in the Hippocampi of Taxi Drivers,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 97, no. 8 (2000): 4398–4403; Stefan Münzer, Hubert D. Zimmer, and Jörg Baus, “Navigation Assistance: A Trade-Off between Wayfinding Support and Configural Learning Support,” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied 18, no. 1 (2012): 18–37; Henry Grabar, “Smartphones and the Uncertain Future of ‘Spatial Thinking,” Citylab, 9 September 2014, www.citylab.com/life/2014/09/smartphones-and-the-uncertain-future-of-spatialthinking/379796/.

4. Anders Engberg-Pedersen, Empire of Chance: The Napoleonic Wars and the Disorder of Things (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015), 165.

5. Dianna L. Van Blerkom, Malcolm L. Van Blerkom, Sharon Bertsch, “Study Strategies and Generative Learning: What Works?” Journal of College Reading and Learning 37, no. 1 (2006): 7–18. The authors are indebted to Navy Captain Mike O’Hara at the Naval War College for his presentation and comments on active reading and encoding through note-taking.

6. Alfred Thayer Mahan, From Sail to Steam: Recollections of Naval Life (New York: Harper and Bros., 1907), 294.

7. Geoffrey Sloan, “The Royal Navy and Organizational Learning—The Western Approaches Tactical Unit and the Battle of the Atlantic,” Naval War College Review 72, no. 4 (Autumn 2019). David Kohnen, Nicholas Jellicoe, Nathaniel S. Sims, “The U.S. Navy Won the Battle of Jutland,” Naval War College Review 69, no. 4 (August 2016).

8. CDR Wolf Melbourne, USN, “Naval Intelligence’s Lost Decade,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 144, no. 12 (December 2018): 44–48.

9. “Information radiator” is a term popularized by computer scientist Alastair Cockburn in his writings on software development processes. Information radiators in a naval staff context were discussed in Trent Hone and CAPT Dale Rielage, USN (Ret.), “No Time for Victory,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 146, no. 5 (May 2020). For a summary of the related concept of the Japanese kanban board, see infoq.com/articles/agile-kanban-boards/.

10. Edward Tufte, Beautiful Evidence (Cheshire, CT: Graphics Press, 2006), 184.

11. Agathon-Jean-François Fain, Mémoires du Baron Fain, Premier Secrétaire du Cabinet de L’empereur (Paris: Libraire Plon, 1909), 39–40. Craig Symonds, Lincoln and His Admirals (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 360. Andrew Rhodes, “The Geographic President: How Franklin D. Roosevelt Used Maps to Make and Communicate Strategy,” The Portolan Journal 107 (Spring 2020). See CDR Christopher Nelson, USN, “A Conversation with Wargaming Grand Master Dr. Phil Sabin,” CIMSEC, 22 July 2016, cimsec.org/lord-wargame-chat-dr-phil-sabin/26631.

12. Sara Brinch, “What We Talk about When We Talk about Beautiful Data Visualizations,” in Martin Engebretsen and Helen Kennedy, eds., Data Visualization in Society (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2020). Maps are not the only large-format analog displays that can serve the intelligence officer well. Recognition charts and wall posters are equally important for staffs.

13. “Pres. Lyndon B. Johnson, Walt Rostow, others look at relief map of Khe Sanh area, Vietnam,” 2 February 1968, Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library, Photo Archive: Image A5635-29, lbjlibrary.net/collections/photo-archive.html; Raymond Drumsta, “NY Guard Soldiers create massive sandtable of National Training Center,” U.S. Army, 12 October 2011, army.mil/article/67057/ny_guard_soldiers_create_massive_sandtable_of_national_training_center; Peter Bergen, Manhunt (New York: Random House, 2012), 164–65.