People are the Navy’s most valuable asset. Yet the service squanders significant warfighting advantage at its most senior ranks—not by policy, but by a culture that has made the effective employment of senior leaders the exception rather than the norm.

In 2017, the U.S. Navy suffered two major collisions, losing 17 shipmates as a result. Throughout the various reviews, investigations, and lessons learned, time was a major theme. Crews, wardrooms, and commanding officers lacked time—for training, for thinking beyond the next requirement or evolution, and even for sleep. Not surprisingly, resulting recommendations focused in part on managing time more effectively and creating rhythms that integrate human needs with mission requirements.

The reality, however, is that the Navy’s time management problem is not restricted to the afloat forces or to its hardworking junior ranks. For many senior Navy leaders, whether in operational or staff assignments, the normal routine leaves them suboptimized for high performance and struggling to find time for deliberate thought and strategic decision-making. Almost universally, they rue their inability to work on the “important but not urgent,” lack time to read and think, much less to effectively communicate their thoughts, and are taxed to find time for the toughest issues that the service must address across all echelons.1 The Navy’s view of time needs to change.

Consider the following representative cases:

- The fleet commander who modeled exceptional self-awareness and deliberate thought on how to approach every mission except in his own scheduling. There, the commander repeatedly expressed his intention to end his tour as “a dried husk,” having given all his energy to the job. He did. Unsurprisingly, despite his encouragement to his staff to moderate their own pace, his subordinates followed his example, leaving a team with no reserves and no margin for the next commander or the next surprise.

- The fleet commander who, pushing himself at a pace that left him essentially mission ineffective because of recurring fatigue, rejected any input from his staff to moderate his pace. His defensive response was “no one tells Michael Jordan to play less basketball”—ignoring that he, unlike great athletes, was deliberately playing injured and hurting the rest of the team.

- The senior officer who, having been directed to take an “unplugged” leave period, called his aide to have the aide read his emails to him over the phone.

- The executive assistant who, reflecting on the impossible schedule his boss was facing over the next week, observed that he could remove every event from the schedule except meetings required by higher headquarters and their volume alone would still consume the commander’s entire day.

- The chief of staff who could be routinely found in his office literally asleep at his keyboard.

- The “essential” officer whose ability to craft staff products is considered so unique that he is driven to “heroic” work hours and routine episodes of all-night work. Having exhausted himself in support of the command, the officer is celebrated for his dedication and rewarded with praise, prestige, and glowing fitness reports, reinforcing perceptions that a suboptimized process is in fact the command goal.

Why Does this Happen?

The Navy is by its nature a “greedy institution.” When sociologist Lewis A. Coser coined that phrase, he applied it neutrally to any organization that “demands an especially fervent and total commitment” in the service of a higher purpose. Coser included such constructs as social and political movements, communes, and religious orders.2 In the years since, the phrase has been used in a negative sense to describe companies expanding their expectations of their employees’ workloads. The relentless commitment and brutal hours expected by some technical firms are a common example.

It is said every vice is a virtue taken to an extreme. In the past two decades, this core Navy virtue—mission-focused commitment—has collided with wider social and technological trends that have pushed it to become a vice. Americans at the top of their professions are working more hours. In a world of increasingly fluid labor, demonstrating commitment to an employer by being constantly available to seniors and customers often is a matter of professional survival. Further, success in many industries bears a nonlinear relationship to work hours. Civilian professionals who work more than 50 hours a week earn significantly more than those working traditional full-time hours. This “overwork premium” is a new development in the American workplace, and it increasingly divides the top 1 percent from the top 10 percent.

At the same time, the ability to collect and disseminate information has increased and dispersed. The traditions of Navy culture—“always call the CO”—and the ability to constantly be in contact, through iPhones, portable secure communications, comms on the airplane when a commander travels, etc., pull senior leaders down into a constant drumbeat of detailed decisions that older technologies would have left to subordinates. The command duty officer or fleet command center can follow you home in your pocket.

The Navy tradition of absolute command responsibility drives a thirst for this information; leaders gather reports, analyses, and facts, until they overwhelm themselves and their higher echelons with data, diluting the value of the essential information those transmissions contain. Video teleconferences occur across the globe at all hours and have created the expectation that senior leaders will be available to participate in them and help guide decisions even if they occur at 0400 local (or earlier). Each hour spent on these calls reduces time available for strategic thought and margin for the unexpected. More than once, senior Navy leaders have expressed hope that someone up the chain of command has time to think, because they do not. In any organization, the most vital factor for overcoming unanticipated challenges is spare capacity; the Navy’s drive for efficiency has left it vulnerable to shock and surprise. The Navy has become brittle.3

Leadership by Example

Because these trends have emerged over several decades, they have an aura of inevitability in the minds of most serving officers. Naval officers always have had limited time to create impact or make an impression during their leadership tours; self-interest and professional interest combine to create impatience in leadership and drive a frenetic pace. Despite that fact, history offers examples of what a different culture can look like. While generally judged as brilliantly successful, by present standards many of the greatest leaders in U.S. naval history were slackers and no-loads.

Consider Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz. Although Nimitz worked long hours during critical moments of World War II, he insisted on a regular routine with deliberate room for recreation and social time that protected his health and that of his staff. A typical work day would flow:

0700 – Breakfast with chief of staff and his medical officer.

0800 – Early morning briefing conducted by a small group of staff members to bring Nimitz up to speed or one-on-one sessions focused on new developments and emerging intelligence.

0900 – Daily conference to bring the wider staff up to speed. Local commanders, staff members, visiting fleet and task force commanders, and senior participants in upcoming operations attended, and the meetings often took the form of a seminar with group discussion.4

1000 – A break, which Nimitz often spent on the pistol range.

1100 – Daily roundtable with commanding officers of ships recently arrived in Pearl Harbor. This “CO’s call” was Nimitz’s way to size up new COs and offer them context for their role in upcoming operations. Communication went both directions; Nimitz noted, “Some of the best help and advice I’ve had comes from junior officers and enlisted men.”5

1230 – Lunch with senior staff members.

Afternoons tended to be less structured. Sometimes, conferences and briefings were held. Otherwise, time was spent reviewing plans and going through paperwork in private. Quieter afternoons often were spent walking, usually with his chief of staff or key staff leaders.

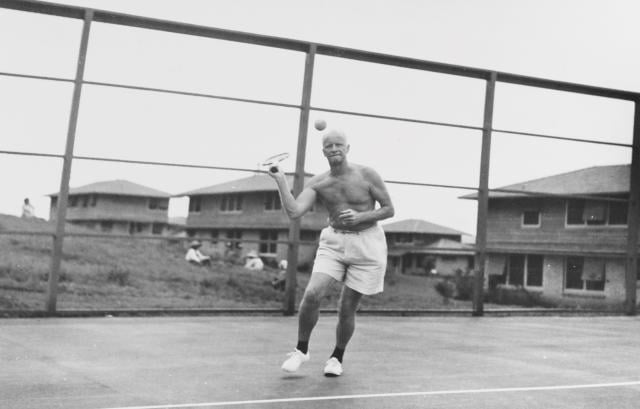

1600 – Set time for recreation. Long walks, games of horse-shoes or tennis, and swimming were common activities.

Evenings were focused on socialization and relaxation. Guests were entertained for dinner, usually preceded by a cocktail hour.

The slack in this schedule was key to allowing Nimitz and his staff to maintain their strategic focus over a long conflict. They preserved their capacity, so that when they had to make the critical decisions of the war, they were prepared and ready. Nimitz’s biographer noted that “the CINCPAC Staff worked seven days a week, often well into the evenings, but no objection was raised if officers knocked off work in the middle of the day and went out for a game of tennis. Certainly, Admiral Nimitz—and Spruance when serving as Nimitz’s Chief of Staff—never hesitated to stop for exercise or relaxation when the pressure was not too great.” This was deliberate. Nimitz wanted “a hard-working staff, kept as small as possible” that was “healthy and efficient.”6

General George C. Marshall, the Army’s Chief of Staff in World War II, was similarly protective of his time and also built opportunities for regular exercise into his routine. He regularly napped in the middle of the day, went horseback riding in the afternoons when his workday finished, and kept set hours. He refused to work long into the night.

Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King, the Navy’s Commander-in-Chief and Marshall’s peer on the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS), lived on board his flagship the USS Dauntless (PG-61) during World War II, because it was quiet and free of distractions.7 His schedule also was full of unstructured time:

0700 – Wake up and exercise.

0730 – Breakfast on board the Dauntless.

0820 – Arrival at Main Navy for work. King regularly took a car to the Mall and walked the rest of the way.

Mornings were kept unstructured except for a standing daily conference with the Secretary of the Navy.

1245 – Lunch. Most days King lunched with his personal staff, including Rear Admiral Charles M. “Savvy” Cooke, the chief planning officer, and Rear Admiral Richard S. Edwards, deputy chief of staff for operations. Once each week, he had lunch with other members of the Joint Chiefs.

At the end of the day, King returned to his flagship and dined with his staff duty officer. He spent time in the evening reading and thinking. Occasionally, he would watch a movie.

On Sunday afternoons, King would go to his official residence on the grounds of the Naval Observatory. This was time for “his daughters, grandchildren, relatives, and family friends.”8

In addition to this relaxation on Sunday afternoons, King made occasional trips to local farms owned by friends—the Dunlaps in Cockeysville, Maryland, and the Phils in the Shenandoah Valley. These visits got King away from the pace of activity in Washington and gave him the time and space to think.9

Not About Work-Life Balance

Each of these leaders would have scoffed at the idea of work-life balance as an end in itself. What they understood—and acted on—was the insight that overtaxing themselves and their senior leaders hurt their mission. While they arrived at this insight from experience and intuition, current research supports the critical impact that overstretch has on leaders and organizations.

- Lack of spare capacity leads to hasty, poorly develop decisions; it prevents individuals from being able to identify, entertain, and develop creative options.

- It reduces resilience—even when leaders love their work—by contributing to medical issues.10

- People are less fair to others when rushed and more prone to judge others harshly.11

- Women generally face more pressure to balance family and societal demands. As a result, greedy institutions offer a particular challenge for women in leadership, making it less likely the organization will benefit from their talents and perspectives.12

- Leaders lack time to develop subordinates.

- Some of those most talented subordinates are hesitant to take on leadership roles because of what they see happening to those above them.

These are the impacts in a peacetime environment. In crisis or combat, each of these issues becomes aggravated. The crush of boards, bureaus, and cells in our operational battle rhythm drives out time for the actual business of command. Aligning deployed battle rhythms to the Washington, D.C., time zone, over and above that of the area of operations, for example, is expected. The Navy fails to recognize the full implications of these habits because the exercises intended to test its processes last no more than two weeks, allowing it to “gut through it” and fool itself that a quick sprint rather than a marathon pace will succeed.

Nimitz was painfully aware of the consequences of this kind of thinking. One of his key subordinates, Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghormley, failed to protect his time and became overwhelmed with details. Tasked with initial operations to seize and hold Guadalcanal in late 1942, he rarely left his flagship, and when the Japanese began their October offensive to retake the island, presented a demoralized and defeatist attitude under the weight of his command. Nimitz reluctantly relieved him. Vice Admiral William F. Halsey Jr., Ghormley’s relief, moved his headquarters ashore as soon as possible, in part to give him and his staff space and an opportunity for exercise.

The military leaders who saw this nation through World War II understood this. They had more time in their schedules to do “nothing”—thinking, reflecting, recreating—which gave them the capacity to identify emerging opportunities, craft deliberate strategic decisions, and act quickly when necessary. Arguably, a deliberate operational pace allowed a faster strategic pace. Consider that the Joint Chiefs of Staff agreed to accelerate the timetable for the invasion of the Philippines in September 1944 within 90 minutes of receiving Admiral Halsey’s recommendation.13

The solutions are straightforward, but not simple. A list of potential steps reads like fundamentals of leadership:

- Officers at all levels must revise their approach to work and delegate more effectively. Nimitz deliberately avoided doing work that his subordinates could do. Officers should follow his lead. Leaders should focus on developing trust and fostering the initiative of subordinates so that they feel comfortable delegating.

- Information management is essential. “Information radiators”—plots, charts, and other visual tools—can create shared understanding and decentralized decision-making without forcing events onto the schedule.

- Don’t use briefings and meetings for decisions; use them to create a common perspective that leads to better decisions on the part of others. Trust them to make those decisions.

So what prevents action? In the Navy today, talking about being overtaxed usually is a form of “humble bragging”—communicating how essential the complainer really is—or is perceived as an admission of personal weakness. As a first step, the service needs to recognize the problem and discuss it openly, the way it would any other core leadership issue. Second, it needs to get past the sense of helplessness that surrounds the discussion. Too many seniors view taking control of their time as a form of unilateral disarmament: “I would unplug, but my boss expects . . .” If the answer at every level—up to and including the four-star level—is that the higher headquarters makes sensible scheduling and time management impossible, then the fundamental culture of the service needs to be questioned.

If the Navy does not make this shift, if it continues to emphasize “efficiency” and “velocity” over operational capacity and strategic foresight, it will be choosing to sacrifice one of its greatest strengths: the ability, aptitude, and talents of its leaders. In a world where the margin of superiority is “razor thin,” it is time to stop scheduling senior leaders into ineffectiveness.

1. We arrived at this conclusion independently, from vastly different backgrounds. One of us has experienced multiple Navy commands, including eight tours on three- or four-star staffs. The other has observed the Navy from the outside as an award-winning naval historian and organizational consultant.

2. Lewis A. Coser, Greedy Institutions: Patterns of Undivided Commitment (New York: The Free Press, 1974).

3. David D. Woods, “The Theory of Graceful Extensibility: Basic Rules that Govern Adaptive Systems,” Environment Systems and Decisions (2018).

4. E. B. Potter, Nimitz (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1976), 222; Adah-Marie R. Miller, “Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, U.S.N., A Speculative Study (A Psycho-Biographical Quest for Qualities of Leadership),” master’s thesis, University of Texas, August 1962, 71–75.

5. Potter, Nimitz, 223.

6. Potter, Nimitz, 227.

7. Thomas B. Buell, Master of Sea Power: A Biography of Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1980), 144.

8. Buell, Master of Sea Power, 430.

9. Buell, Master of Sea Power, 285.

10. Gianpiero Petriglieri, “Is Overwork Killing You?” Harvard Business Review, 31 August 2015.

11. Elad N. Sherf, Ravi S. Gajendran, and Vijaya Venkataramani, “Research: When Managers Are Overworked, They Treat Employees Less Fairly,” Harvard Business Review, 4 June 2018.

12. Claire Cain Miller, “Women Did Everything Right. Then Work Got ‘Greedy,’” The New York Times, 29 April 2019.

13. Henry H. Adams, Witness to Power: The Life of Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1985), 259.