Service at sea is not without its hardships, but for a career cutterman, there is nothing quite like the call of the sea. So it was no wonder that during a unit visit, the master chief from headquarters was in high spirits to be out in the fleet. Walking around the fast response cutter (FRC), he eagerly greeted everyone he passed, and when he sat down on the mess deck, he exclaimed, “Ah, patrol boat life, does it get any better?”

Truthfully, though, the Coast Guard needs to stop calling the FRCs patrol boats.

It was not the master chief’s fault that he made the frequently used, but very misleading, “patrol boat” reference to the FRC. He was viewing it through the lens of his own career. It is common to hear senior enlisted and officers refer to their “patrol boat days”—usually referring to their own service on 82s, 87s, or 110s, all patrol boats. However, that frame of reference does an injustice to the FRC’s capabilities. While the FRC replaced the Island-class 110, doing so was akin to upgrading from a muscle car to James Bond’s Aston Martin. Treating the FRC as a patrol boat, especially in high operational tempo districts such as the Seventh and Eleventh, is misguided and negatively affects training, maintenance, and operational employment.

What’s Wrong with the PB Model?

The FRC has been called many things. Some call it a “PB.” Others call it a “game changer,” or, more accurately, an “endgame changer,” because of its capabilities and success in counterdrug/migrant interdiction operations. And the FRC is capable. It effectively has the same capabilities as a medium endurance cutter, minus the flight deck.

The problem with the FRC is not its capabilities, but the service’s understanding, employment, and support of the platform. The Coast Guard has had the FRC in its inventory for eight years, and while thoughtful concepts of how to use it have been discussed—and there have been successes—the main achievement has been a one-for-one replacement of the 110s. For years, the FRC was just plug-and-play—decommission a 110 and replace it with an FRC that would complete legacy missions in legacy ways. Carrying a more capable cutter boat and having extra space on board were improvements over the 110, but during the early days, the majority of the FRC’s advanced capabilities were allowed to languish and, in many cases, ceased working altogether. So, rather than rising to its potential, the FRC simply became a PB. But it does not need to stay that way.

Training and Crewing

Fewer Crew, More Burnout

The FRC has the same, if not more, technology as a 210-foot medium endurance cutter, yet two-thirds fewer crew. This means some critical ratings are not found on board the FRC, leading to heavier workloads, more stringent qualification requirements, and, ultimately, burnout. The best example is the E-4 and E-5 electronics technicians. They are charged with being not only electronics technicians, but also operations specialists and information systems technicians—managing communications security, command-and-control systems, and unclassified and classified information technology systems, to name a few. They also are required to qualify as quartermasters of the watch to stand duty at sea.

The level of dedication required of these junior petty officers is far beyond anything on board a medium endurance cutter, where there are more senior and experienced technicians doing far less. Ultimately, burnout quickly occurs because the FRC is “optimally manned” for underway operations, not for in-port maintenance. Personnel cannot operate at sea and be expected to also work nonstop in port conducting maintenance and casualty response on such a technically demanding platform.

Short Touring

The Coast Guard policy of advancing to fill vacancies also continues to hurt FRC readiness. Just when a crewmember qualifies, he or she advances to the next paygrade and gets short-toured off the ship, disrupting readiness and leaving limited opportunities for incoming crew to complete pipeline training requirements, let alone maintain personal family stability. There also is a drastic knowledge loss when commissioning crews transfer off ships, taking with them the intimate understanding of onboard systems learned during precommissioning training. Pipeline training is time-consuming and just adequate to teach the basics, in most cases.

Inexperienced Leadership

Finally, training and crewing must start from the top down. It is risky to frock lieutenants with less than four years of service and give them command of an FRC. The Coast Guard’s most dangerous rationalization for this is, “It’s just a PB.” Again, an FRC is not an 87-foot patrol boat, in which junior commanding officers can afford to make mistakes and learn. Operational commanders, and, most important, crews, deserve experienced leaders in command of FRCs—especially in high operational tempo districts, where the consequences of mistakes are serious. The same should be said about the engineering petty officer billet; too many E-7s are quickly overwhelmed by the machinery plant, personnel, administration, systems, and general demands of the position on board the FRC.

Maintenance

Along with their many advanced capabilities, FRCs come with exhaustive maintenance requirements—far beyond those of legacy PBs. The newly instituted Operational Driven Maintenance System (ODMS) is an exciting prospect for the FRC fleet, as it seeks to plan out “flexible” maintenance packages built around operations. These packages help ensure schedules contain “dedicated” time to complete preventive maintenance.

However, the challenge for crews implementing the maintenance packages remains the same: time. In-port periods still require training (range quals, law enforcement training, general military training, etc.), inspections, and, the most elusive goal of all—some downtime for rest and family. Finally, the operational (unit-completed) versus depot-level (support-entity–completed) maintenance split remains contentious, with outside entities charged with providing support, yet individual units being left accountable.

Organization by Squadron

The answer to not treating FRCs as PBs, while ensuring FRC sustainability, starts in history, with a return to the division/squadron model.1 As with the surface effect ship (SES) division out of Key West in the 1980s and ʼ90s, an experienced post-command O-5 should serve as commodore or squadron commander to mentor and ensure the personnel, maintenance, and training readiness of a squadron comprising of six to eight cutters.2

The squadron design would give districts operational control, a true center of gravity charged with preparing FRCs for operations—a model with accountability and ownership that is supervised by cuttermen. The squadron would serve as administrative control, while sectors and districts serve as tactical control, employing the resources. Along with creating a shoreside esprit de corps, with the squadron taking pride in its joint achievements, there also would be real accountability within the squadron construct over critical support services, evaluation rating chains, maintenance, and mission preparation. Specific locations ideal for FRC squadrons are the current hubs of Miami, Key West, Puerto Rico, and Los Angeles–Long Beach.

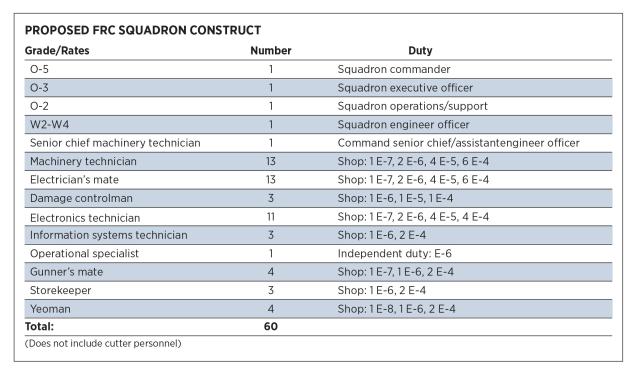

The squadron senior staff should be lean, yet able to provide expertise and support to their cutters. Along with the squadron commander, a post-FRC executive officer should fill a deputy (lieutenant) billet; both of these officers could also provide emergency command cadre relief if needed. Perhaps most critical would be a chief warrant officer (naval engineer) to serve as squadron engineer officer.

The engineer officer would be the vital link supporting the cutter engineering petty officers, while also supervising the maintenance teams and linked directly to the patrol boat product line. This removes the current cumbersome and confusing flowchart of sector engineer officers, port engineers, base naval engineering, maintenance assistance team, and engineering support teams—all with different agendas, priorities, and bosses. The current construct of maintenance assistance team and electronic support detachment personnel, working for external bases with leadership in distant locations, blurs responsibilities and accountability. It is easy to avoid providing the support required when there is no local ownership of the total package.

For example, the current process of routing support “service requests” through a bureaucratic maze, simply to have a damage controlman weld on a cutter, is grossly inefficient and must be simplified to a squadron engineer officer detailing his or her own personnel to support a cutter as needed. Moreover, when an FRC returns from a patrol, it should be flooded by squadron support services waiting on the pier to discuss and lead repairs and complete the majority of maintenance; this allows the cutter crew to focus on operations, training (an ever-increasing requirement), and inspections. This is akin to the superior support provided to Patrol Forces Southwest Asia cutters by shoreside personnel.

This also is a superb opportunity to actually implement a 1:3:1 construct for personnel stability—technical rates would be assigned to the squadron for a year, where they would complete pipeline training, work on underway qualifications, and gain technical expertise, and then be assigned to an FRC for two to three years. They then would return to the squadron to complete their remaining one to two years supporting the ships, with true experience and ownership.

This model also enables cutters (and enlisted detailers) to deal more efficiently with enlisted advancements. Yet another advantage is that the squadron becomes the first source of supply for all surge staffing requests. Need a qualified machinery technician to backfill an injury? The squadron can detail someone already qualified. Finally, a small supporting staff of yeomen, storekeepers, and operations specialists would help manage the squadron ashore.

Command with Experience and Personnel Adjustments

FRCs operating in high operational tempo districts require experienced commanding officers (COs). The best training and experience an FRC CO can obtain is from serving as an operations officer on a major cutter.

It should be the norm, rather than the exception, for FRC COs to get command after having served a lieutenant or lieutenant commander department head tour as operations officer or combat systems officer. The learning curve, especially the navigation, patrol planning, and opportunity to learn from an experienced O-5/O-6 CO on a major cutter, is too valuable to forgo. Moreover, a department head tour teaches future junior COs how to employ the advanced FRC systems operationally—particularly in the counterdrug mission. This experience, plus senior mentorship from the squadron commander, would help ensure the FRC is employed to its maximum potential.

Some adjustments to the personnel allowance list, including substituting a billet for an operations specialist and filling empty racks with two extra non-rates, are additional opportunities for the FRC. The squadron construct also provides an improved rating chain, enabling more accurate evaluations based on performance and removing significant administrative burdens from sectors and districts.

Operational Employment

The squadron would be charged with conducting ready-for-operations determinations, expertly ensuring that tactical and operational control are receiving units ready to deploy in support of entities such as Joint Interagency Task Force South. In addition, by giving the squadron administrative control over FRCs, sectors and districts are freed to focus on planning operations and relieved of day-to-day management duties. Tactical and operational control would be able to focus on new initiatives, such as building surface action groups linking FRCs with a major cutter, especially a national security cutter, to build endgame packages.

In addition, squadrons would be the natural place to test and evaluate new tactics for operations quickly and to prevent knowledge and experience from being lost on such technical ships. The squadron would raise the bar on what the FRC can achieve operationally.

Suggesting that the Coast Guard stop calling an FRC a patrol boat is certainly tongue-in-cheek; however, the service must begin employing and supporting the FRC for what it was designed and equipped to do. It can start by changing the organizational setup and support matrix to drive improvements in training, readiness, and operational success. Bringing back a squadron administrative control structure, coupled with a few other organizational changes, will help improve accountability and finally push the FRC past a PB legacy and into the future it deserves.

1. ALCOAST 214/18—JUN 2018 “Accelerating toward Our Future,” content.govdelivery.com/accounts/USDHSCG/bulletins/1f45740.

2. CDR Ray Bland, USCG, “Tactical Employment of Surface Effect Ships,” The Bulletin (January–February 1983).