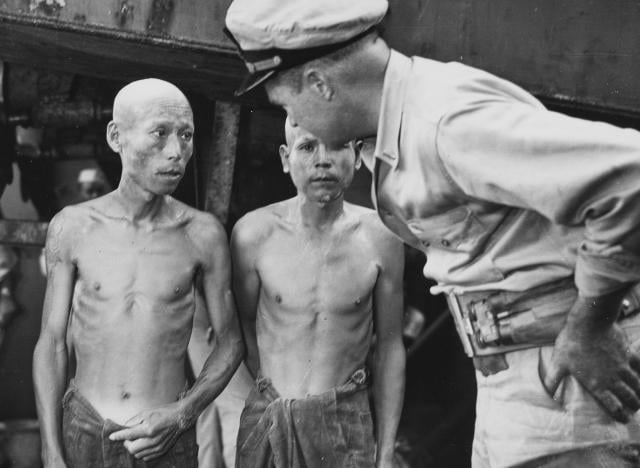

In November 1942, the Japanese army on Guadalcanal was starving to death. Lieutenant General Harukichi Hyakutake reported that his troops were living on nothing more than water and grass, with 100 dying of starvation each day.1 By January 1943, it was 200 per day.2 A brutally honest Japanese lieutenant recorded a life expectancy chart in his diary:

He who can rise to his feet: 30 days left to live

He who can sit up: 20 days left to live

He who must urinate while lying down: 3 days left to live

He who cannot speak: 2 days left to live

He who cannot blink his eyes: dead at dawn3

On 7 February, the final remnants of the Imperial Japanese 17th Army were evacuated. Fifteen thousand had died from starvation, three times the number lost in combat.4 After the war, a Japanese veteran of the fighting and starvation remarked that Guadalcanal is “no longer merely a name of an island in Japanese military history. It is the name of the graveyard of the Japanese Army.”5

The Japanese Army lost on Guadalcanal because it could not reliably supply its forces. Guadalcanal was not unique, only the best known example. Imperial Japanese garrisons faced starvation across the Pacific. Some even resorted to cannibalism as the Allied campaign bypassed islands and left them to “wither on the vine.”6 A chronic failure to account for logistics and supply expeditionary forces with even basic necessities such as food—let alone ammunition and other matériel—crippled Japan’s war effort.

By 1945, the populace in the Home Islands also faced starvation, but in 1942 there was more than enough food to supply the soldiers at Guadalcanal and elsewhere; the problem was getting it there. The Japanese Navy in 1942 still was roughly equivalent to the U.S. Navy in combat power, and Japan still had a robust merchant marine. The most important difference between the two navies was logistics: Japan could not keep its forces supplied in a contested environment. Today, the United States faces the same problem.

Right Analogy . . .

Guadalcanal has become popular as a historical analog for the Marine Corps’ expeditionary advanced base operations (EABO) concept as well as the Army’s multidomain operations concept.7 According to Commandant of the Marine Corps General David H. Berger, EABO will enable:

the naval force to persist forward within the arc of adversary long-range precision fires to support our treaty partners with combat credible forces on a much more resilient and difficult to target forward basing infrastructure.8

Marines will operate in smaller, more widely distributed groups than ever before and will have to make substantial investments in new technologies such as autonomous vehicles and long-range precision fires.

The inherent risk in EABO is that traditional maritime logistics will be unable to support and sustain these groups in the contested environment. U.S. forces may not have access to stocks and supplies prepositioned in other nations. Unfortunately, EABO concepts only exacerbate this long-standing problem. Marine and Navy leaders and outside agencies have been calling attention to it for years.

. . . Wrong Side

General Berger underscored in 2019 the need for innovation in expeditionary logistics in the Commandant’s Planning Guidance:

To succeed in closing the force in any future conflict, we must re-imagine our . . . prepositioning, and expeditionary logistics so they are more survivable, at less risk of catastrophic loss, and agile in their employment.9

Almost a year later, the Commandant again warned that the Corps is not making sufficient progress:

I am not confident that we have identified the . . . logistical sustainment needed. . . . I do not believe our Phase I and II efforts gave logistics sufficient attention.10

But much of the conversation around operationalizing EABO remains focused on fires, not what will be required to make possible and sustain those fires. Without addressing EABO’s looming logistical challenges, the Marine Corps could well recapitulate the fight for Guadalcanal—but from the Japanese perspective.

Capability Gaps

The Navy lacks at every level the logistics forces to support a large Pacific campaign, from strategic sealift to over-the-beach logistics. Military Sealift Command operates and crews the 125 ships that replenish the Navy at sea and transport troops and cargo around the world, but it is in dire straits. A recent Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments report concluded: “Absent dramatic improvements, U.S. sealift forces would face major challenges and may fail to meet Joint Force demands in a major war.”11 A 2017 Government Accountability Office report found similar shortfalls.12 And a recent Department of Defense Inspector General investigation found that Military Sealift Command chronically misrepresented ship readiness—implying that the problems watchdogs and analysts identified are even worse than reported.13

The Navy’s fleet of large L-class amphibious ships, which are designed to deploy and sustain Marines in combat, is chronically understrength; it has been years since the Navy purchased enough to meet the Marine Corps’ stated requirement of 38. In 2019, in the face of growing concern that these large, slow, and overt vessels would not survive in a peer fight, and with no indication the Navy would reach the specified number, General Berger dropped it altogether.14 The Marine Corps has asked shipbuilders for proposals for a new class of smaller, more numerous amphibious ships. However, any such ships will probably be a far cry from the “affordable and plentiful” platforms the Commandant has called for and would do little to solve the intertheater logistics problem.15

The state of intratheater and over-the-beach logistics also poses an immediate and critical gap for Marines.16 Former Commandant General James F. Amos wrote a prescient article in 2013 forecasting a “significant gap in the planned surface-connector fleet.”17 Today, Marines are living with that gap. Marginal improvements over legacy designs such as the Amphibious Combat Vehicle and “fighting connectors” can help solve the problems associated with a contested beach landing, but not the problems associated with a much larger contested region.18

Clandestine Logistics

The Navy and Marine Corps need a clandestine logistics capability. Such a capability would allow the United States to sustain stand-in forces operating inside an adversary’s weapons engagement zone (WEZ) indefinitely. Without it, stand-in forces would “wither on the vine,” much like the Japanese forces spread across the Pacific did during World War II. A western Pacific war could become a stalemate—with both sides able to deny use of large zones to the other, but neither gaining sea control to use the zones itself. Unarmed or lightly armed logistics vessels would be easy targets, and China’s military has made clear those ships will be targeted in a potential conflict.19 With traditional logistics shut out, only clandestine logistics platforms will be able to sustain the inside forces.

What would such a capability look like? It would comprise platforms in the air, on the sea, and below the surface. A starting point could be a mix of amphibious aircraft; small, high-speed utility vessels; and low-profile vessels. None of these are completely clandestine, but all have reduced observability compared to comparable traditional platforms. New types of fuel could offer real advantages—they are safer to transport and store than fossil fuels and reduce the infrared and exhaust signatures of combustion engines. Working together in operationally relevant numbers, this platform mix can change the logistics paradigm.

Amphibious Aircraft

Amphibious aircraft are only a few years younger than aircraft themselves—the first was flown in 1911, only eight years after the Wright Brothers’ first flight.20 What makes amphibious aircraft unique is their ability to land either on conventional runways or on water—lagoons, rivers, lakes, bays, or even the open ocean.

They are large enough to carry passengers and cargo long distances and deliver them to areas that do not have developed aviation infrastructure. The Consolidated PBY Catalina and the Grumman Albatross are two of the best-known historical examples. Catalinas served across the Pacific in World War II and were produced by the thousands for transport, reconnaissance, strike, and search-and-rescue roles. The Albatross served in the Navy until the 1970s, in the Coast Guard into the 1980s, and in international service through the 1990s as an antisubmarine warfare platform. Today, both Russia and China are investing in amphibious aircraft. China’s new AG600 is roughly the size of a Boeing 737 and boasts a range of 2,800 miles.21 Japan’s US-2 amphibious aircraft, with an operational range of 2,900 miles, is ideal for operating in the western Pacific.

Amphibious aircraft are not necessarily clandestine, but because they are not tethered to fixed runways and related infrastructure, they can be tactically and operationally unpredictable and therefore much more difficult for an enemy to target than land- or even carrier-based aircraft. Traditional intertheater assets such as the C-17 Globemaster are tethered to runways that can easily be targeted at long range. Helicopters, while much more versatile, lack the range to cover the long distances in the Pacific without air-to-air refueling.

Small Boats

Small, fast boats capable of serving in a utility role are invaluable. Their size and cost are typically proportional; their low cost makes them inherently more risk worthy than larger ships, while their small size protects them by hiding them in littoral and wave clutter. High speed helps protect them in an engagement. The Navy’s Mk VI patrol boat, the Swedish CB90, or even the Coast Guard’s fast response cutters could provide ready models for a fast utility boat. The Marine Corps and Navy also are experimenting with small unmanned surface vessels, which could be ideal for resupply missions.22 Small boats are also valuable in roles such as maritime reconnaissance and strike.

While small boats do not have the carrying capacity of larger ships, they can link fleet logistics ships parked safely outside the WEZ with stand-in forces. The Whidbey Island–class amphibious ships can comfortably hold eight Mk VI boats in their well decks. Narcotics traffickers in the Caribbean often transfer illicit cargos between “go-fast” boats as part of a high-speed shell game that could be a model for resilient Navy–Marine Corps logistics for the Pacific.

Low-Profile Vessels

Low-profile vessels (LPVs) are the third unique capability ideally suited for clandestine logistics. Again, narcotics smugglers offer a possible model; LPVs from the Caribbean and eastern Pacific have been intercepted as far away as the coast of Spain.23 LPVs operate almost totally submerged, with only a small snorkel and cockpit visible above the surface. Inside they carry a few crew members and several tons of cargo. And LPVs are growing in size—the Colombian military recently captured possibly the largest built to date, with a potential cargo capacity of more than eight tons.24 Even after at least three decades of use, they remain difficult to detect and intercept—just ask the Coast Guard.

With mild improvements, these vessels could carry tens of tons of cargo thousands of miles between safe logistics hubs and stand-in forces in the Pacific, and they are excellent candidates to be unmanned systems. These vessels would travel slowly but would be almost invisible while transiting from safe logistics hubs in Guam or Australia to Marine Corps forces deep inside the WEZ, delivering food, munitions, or other vital warfighting material to keep expeditionary forces in the fight.

Low-Signature Fuels

The logistics chain that supplies bulk fuel to forward units is often highly visible, taking the form of vulnerable oilers and fuel truck convoys. In Iraq and Afghanistan, where U.S. forces used as much as 22 gallons of fuel per soldier per day, a disproportionate number of U.S. casualties came from fuel convoys.25 Engineers at Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Lincoln Laboratory (where one author works) and elsewhere have demonstrated that novel nonliquid fuels such as specially treated aluminum can help reduce expeditionary forces’ dangerous dependence on petroleum.26

Aluminum has almost double the energy density of diesel fuel and presents none of the fire hazards during transport. Aluminum can even be sourced locally from trash and recycled materials—hidden in plain sight, in other words. When activated for fuel, it produces hydrogen, which in an efficient fuel cell generates a lower thermal signature than combustion engines and none of the visible exhaust, only water. Shifting from liquid fossil fuels to inert solid fuels and hydrogen fuel cells would dramatically reduce the logistics needs of expeditionary forces—and the need to send vulnerable oilers across the open ocean.

Toward a Resilient Future

The Navy and Marine Corps need to develop a resilient logistics capability that will enable them to sustain expeditionary forces forward in contested environments. Naval theorist and Proceedings author Milan Vego has argued that the outcome on Guadalcanal depended on who could better control the sea to “supply and reinforce ground troops contending ashore for mastery.”27

If the Department of Defense does not experiment with new technology and concepts in naval logistics, Marines and sailors operating ashore could face a fate similar to the Imperial Japanese forces in World War II. The most effective way to do this is through a variety of complementary platforms that can be clandestine and operationally unpredictable and fueled by more readily sourced, safer, lower-signature, easily hidden, nonpetroleum fuel. Together, these kinds of platforms will ensure that no Marine Corps officer will ever keep a grim table of starvation like the one kept by a Japanese lieutenant on Guadalcanal.

1. John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire, 1936–1945 (New York: The Modern Library, 1970), 418–19.

2. Lizzie Collingham, The Taste of War: World War Two and the Battle for Food (London: Penguin Books, 2011), 292.

3. Jobie Turner, Feeding Victory: Innovative Military Logistics from Lake George to Khe Sanh (Lawrence, KS: Kansas University Press, 2020), 140, and Richard B. Frank, Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle (New York: Penguin Books, 1992), 527.

4. Collingham, The Taste of War, 293.

5. Joseph Wheelan, Midnight in the Pacific: Guadalcanal, the World War II Battle that Turned the Tide in the Pacific (New York: DaCapo Press, 2017) 297.

6. Collingham, The Taste of War, 297–98.

7. Brandon Morgan, “Guadalcanal in World War II: Conducting Multi-Domain Operations before It Had a Name,” Modern War Institute at West Point, mwi.usma.edu, 11 December 2019.

8. GEN David H. Berger, USMC, Commandant’s Planning Guidance (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, July 2019), 11.

9. Berger, Commandant’s Planning Guidance, 20.

10. GEN David H. Berger, USMC, Force Design 2030 (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, July 2020), 10.

11. Timothy Walton, Ryan Boone, and Harrison Schramm, Sustaining the Fight: Resilient Maritime Logistics for a New Era, Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments (April 2019), 76.

12. Report to Congressional Committees, “Actions Needed to Maintain Viable Surge Sealift and Combat Logistics Fleets,” Government Accountability Office (August 2017), www.gao.gov/assets/690/686733.pdf.

13. Department of Defense Office of Inspector General, Audit of Surge Sealift Readiness Reporting (22 January 2020).

14. Shawn Snow, “Marine Commandant Drops 38 Amphibious Ships to the Fight Requirement,” Marine Corps Times, 19 July 2019.

15. Berger, Commandant’s Planning Guidance, 4.

16. Elee Wakim, “For Want of a Nail: Surface Connectors in Expeditionary Logistics,” War on the Rocks, 18 August 2018, warontherocks.com.

17. GEN James F. Amos, USMC, “Bridging Our Surface-Connector Gap,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 140, no. 6 (June 2014).

18. Douglas King and Brett Friedman, “Why the Navy Needs a Fighting Connector: Distributed Maritime Operations and the Modern Littoral Environment,” War on the Rocks, 10 November 2017, warontherocks.com.

19. Peter Suciu, “The Really Boring Way China Would Try to Win a War against America,” The National Interest, 9 June 2020, nationalinterest.org.

20. “Curtiss A-1 Triad,” San Diego Air and Space Museum, sandiegoairandspace.org/collection/item/curtiss-a-1-triad.

21. “China’s AG600 Amphibious Aircraft Completes Maiden Flight over Sea,” CGTN, 26 July 2020, news.cgtn.com.

22. David B. Larter, “With U.S. Marines Seeking Unmanned Logistics to Fight China, Textron Sees Opportunity,” Defense News, 15 January 2020, www.defensenews.com.

23. Sam Jones, “Cocaine Seized from ‘Narco-submarine’ in Spain Was Likely Headed for UK,” The Guardian, 27 November 2019.

24. H. I. Sutton, “Unusually Large Narco Submarine May Be New Challenge for Coast Guard,” Forbes, 10 August 2020.

25. Elizabeth Rosenthal, “U.S. Military Orders Less Dependence on Fossil Fuels,” The New York Times, 4 October 2010.

26. “General Atomics Awarded Army Contract for Hydrogen Generation System Prototype,” 7 November 2019, www.ga.com/general-atomics-awarded-army-contract-for-hydrogen-generation-system-prototype; “Tech Notes: Aluminum as a Fuel,” MIT Lincoln Laboratory, March 2017, archive.ll.mit.edu/publications/technotes/Aluminum-as-fuel.html.

27. Milan Vego, Naval Strategy and Operations in Narrow Seas (New York: Frank Cass, 1999), 119.